Strengthening domestic evidence-support systems | Global Commission on Evidence to Address Societal Challenges

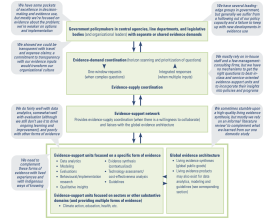

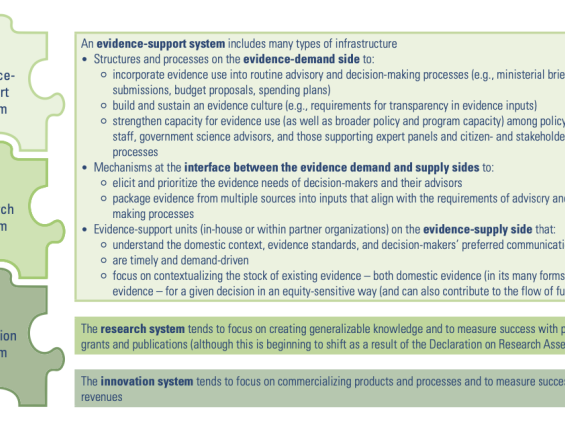

To formalize and strengthen domestic evidence-support systems, the Evidence Commission’s secretariat and partners in 12 countries are conducting rapid evidence-support system assessments, or RESSAs, and sharing lessons learned through the RESSA Country Leads Group. The goal in each country is to identify what is going well that needs to be systematized and scaled up, and what gaps should be prioritized to fill, and to work with government policymakers, organizational leaders, professionals and citizens to push for improvements. Conducting a RESSA starts with an understanding of what a domestic evidence-support system is and how it differs from research and innovation systems (see Pic1; Link1, p.6). Drawing on websites, documents and interviews, a RESSA involves asking questions (see Link1, p.6-7) about each of the potential features of an evidence-support system (see Pic2 – shown in light green), as a baseline, and taking action based on what is learned.

Contexte

Challenges addressed

Emplacement

Impacts

Based on a total of 39 currently active RESSAs underway (representing a mix of national, subnational and sectoral foci across 12 countries), we see that most countries include few of the features of an evidence-support system, and even fewer are working optimally, especially when crises emerge. Examples of the types of things we are hearing from the RESSAs are provided (see Pic2 – shown in light grey). See also a documented (and sector-specific) example of a RESSA in the Canadian context (see Link2), and a list of country leads (see Link3). In terms of the actions underway at the country-level, on the demand side, there are emerging examples such as the legislative requirements for transparency in evidence inputs as is required now in Australia’s New South Wales. On the evidence-supply side, a number of innovations have emerged including: 1) ultra-rapid evidence support, which can now work with the same speed as policy processes; 2) evidence-supply coordination that can leverage all needed forms of evidence; 3) one-stop shops of evidence syntheses that can help with the global evidence; and 4) ‘living’ evidence syntheses that allow for the best available evidence to be monitored as the context, issue and evidence evolve.