Reforzar los sistemas nacionales de apoyo a la evidencia | Comisión Global de Evidencia para Abordar los Retos de la Sociedad

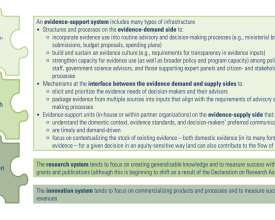

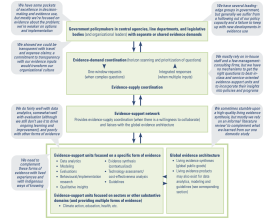

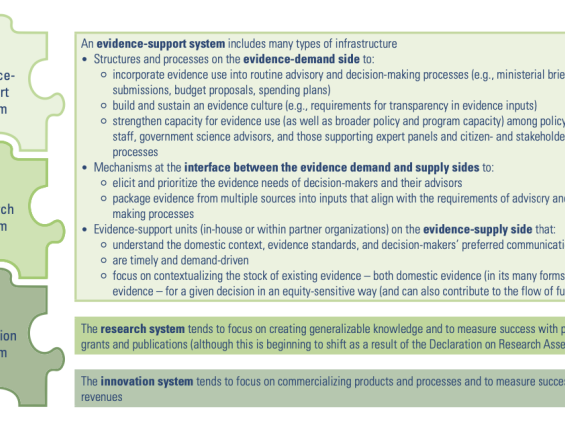

Para formalizar y fortalecer los sistemas nacionales de apoyo a la evidencia, la secretaría de la Comisión de la Evidencia y sus socios en 12 países están llevando a cabo evaluaciones rápidas de los sistemas de apoyo a la evidencia, o RESSA, y compartiendo las lecciones aprendidas a través del RESSA Country Leads Group. El objetivo en cada país es identificar lo que funciona bien y debe sistematizarse y ampliarse, así como las lagunas que deben subsanarse con carácter prioritario, y colaborar con los responsables políticos de los gobiernos, los líderes de las organizaciones, los profesionales y los ciudadanos para impulsar las mejoras. La realización de un RESSA empieza por comprender qué es un sistema nacional de apoyo a la evidencia y en qué se diferencia de los sistemas de investigación e innovación (véanse la imagen 1 y el enlace 1, pág. 6). A partir de sitios web, documentos y entrevistas, un RESSA implica formular preguntas (véanse los enlaces 1 y 7, págs. 6 y 7) sobre cada una de las posibles características de un sistema de apoyo a la evidencia (véase la imagen 2, en verde claro), como punto de partida, y tomar medidas en función de lo aprendido.

Contexto

Défis à relever

Ubicación

Impactos

Sobre la base de un total de 39 RESSA actualmente en curso (que representan una mezcla de enfoques nacionales, subnacionales y sectoriales en 12 países), vemos que la mayoría de los países incluyen pocas de las características de un sistema de apoyo a la evidencia, y aún menos están funcionando de manera óptima, especialmente cuando surgen las crisis. Se proporcionan ejemplos de los tipos de cosas que estamos escuchando de los RESSA (ver Pic2 - se muestra en gris claro). Véase también un ejemplo documentado (y específico de un sector) de una RESSA en el contexto canadiense (véase Enlace2), y una lista de países líderes (véase Enlace3). En cuanto a las medidas en curso a nivel nacional, en lo que respecta a la demanda, hay ejemplos emergentes como los requisitos legislativos de transparencia en la aportación de pruebas, como se exige ahora en Nueva Gales del Sur (Australia). En cuanto a la oferta de pruebas, han surgido varias innovaciones, entre ellas 1) el apoyo ultrarrápido a las pruebas, que ahora puede funcionar con la misma velocidad que los procesos políticos; 2) la coordinación del suministro de pruebas que puede aprovechar todas las formas necesarias de pruebas; 3) las ventanillas únicas de síntesis de pruebas que pueden ayudar con las pruebas globales; y 4) las síntesis de pruebas "vivas" que permiten supervisar las mejores pruebas disponibles a medida que evolucionan el contexto, el problema y las pruebas.