MSP pour la gestion intégrée de la pêche dans le nord du golfe de Californie, phase I

Dans le corridor biologique de Puerto Peñasco à Puerto Lobos (Sonora), un processus d'aménagement de l'espace côtier et marin et de gestion de l'écosystème est en train de voir le jour. Il s'agit d'un cadre permettant de résoudre les conflits croissants entre les différents acteurs/utilisateurs de la région et d'un mécanisme permettant d'assurer la gestion de l'écosystème. Grâce à un processus ascendant, les utilisateurs traditionnels (pêcheurs et ostréiculteurs) participent à la conception de solutions spatiales avec une équipe de gestion composée de scientifiques et de représentants du gouvernement.

Contexte

Défis à relever

Selon les pêcheurs, les principaux problèmes de l'écosystème du corridor sont les suivants : 1) le manque de permis de pêche ; 2) la pêche illégale (manque de respect de la loi) ; 3) le manque de surveillance et d'application (manque d'application de la loi) ; 4) l'entrée de pêcheurs d'autres régions avec des restrictions ; 5) l'éloignement des grandes villes et les coûts élevés ; 6) les conflits avec les pêcheurs industriels ; 7) le manque d'outils de gestion adéquats ; 8) la perte de sites de débarquement en raison de l'augmentation du développement côtier.D'autres défis ont été identifiés : 1) le manque de structure sociale ou d'expérience pour travailler ensemble afin de résoudre les problèmes au sein du secteur de la pêche, entre les communautés et entre les autorités gouvernementales locales, régionales et nationales ; 2) l'évolution de la dynamique sociopolitique et des restrictions de gestion dans la réserve de biosphère adjacente du haut golfe de Californie et du fleuve Colorado, où le principal moteur de gestion est la conservation de deux espèces endémiques et menacées : le vaquita et le totoaba.

Emplacement

Traiter

Résumé du processus

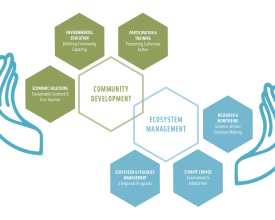

L'approche de la CEDO concilie le développement communautaire et la gestion de l'écosystème. Notre pierre angulaire est la confiance et les relations sérieuses, ce qui se fait tout d'abord en engageant les communautés à identifier leurs besoins, ce qui implique généralement des questions socio-économiques, et en les aidant à résoudre le problème de leur point de vue. La création d'une structure et d'un processus de gouvernance transparents, inclusifs et impliquant des interactions avec d'autres secteurs pour trouver des solutions permet de développer des relations significatives et une action collective. Le renforcement des capacités par l'éducation permet aux communautés de travailler ensemble et de prendre de bonnes décisions. La participation active des parties prenantes à tous les aspects du processus, en leur donnant la possibilité de contribuer en générant des informations, en communiquant et en prenant des décisions, est essentielle pour maintenir l'engagement et promouvoir une société active qui prend en charge son avenir. En intégrant les connaissances traditionnelles et la science pour produire un processus axé sur la science, nous contribuons à créer un langage commun pour toutes les parties prenantes, qui devient la norme pour mesurer l'efficacité de la gestion. La participation des parties prenantes au suivi renforce la conception des outils de gestion des pêcheries et des écosystèmes.

Blocs de construction

Instaurer la confiance et des relations constructives

Notre approche initiale avec les pêcheurs a consisté à les aider à identifier les problèmes auxquels ils étaient confrontés. La pêche étant leur principale activité économique, nous nous sommes attachés à répondre à leurs besoins dans cette optique. Ils ont exprimé le besoin d'obtenir des permis de pêche, et nous avons donc commencé à les aider dans le processus d'enregistrement de leurs bateaux - une première étape - et à les mettre en contact avec le gouvernement qui est responsable de l'octroi des permis.Nous avons contribué à la mise en place d'une structure de gouvernance et d'un processus transparent et inclusif qui permet aux pêcheurs d'accéder au gouvernement en amenant ce dernier à la table des négociations pour résoudre leurs problèmes. Individuellement, ils n'étaient pas en mesure d'attirer l'attention du gouvernement. Cela a permis d'établir des relations de travail avec les autorités, qui doivent répondre directement aux parties prenantes, en établissant des relations significatives en cours de route. Le programme Corridor répond à leurs besoins, en particulier à leurs besoins économiques. En plus d'aider les pêcheurs à clarifier leurs droits de pêche et à s'orienter vers une pêche plus durable, nous identifions également d'autres options économiques intéressantes pour les communautés, telles que l'écotourisme, et nous les aidons à trouver les ressources nécessaires pour les faire progresser en tant qu'options économiques durables. Nous mettrons également les pêcheurs en contact avec des marchés durables.

Facteurs favorables

La confiance. Il est difficile pour une organisation environnementale de mener un tel processus avec les pêcheurs, car ce secteur est connu pour être fortement axé sur les résultats de la conservation. L'organisation chef de file qui facilite ce processus, l'ODEC, travaille dans les communautés de la région depuis 37 ans et a établi un climat de confiance avec les pêcheurs pour travailler ensemble. La persistance de l'ODEC et sa volonté de les aider à résoudre leurs problèmes, ainsi que son propre agenda, ont permis d'établir une relation de travail et de confiance avec les pêcheurs.

Leçon apprise

La confiance des pêcheurs est influencée par de nombreux facteurs. Certains tentent de saper la confiance des pêcheurs dans l'ODEC en lançant des rumeurs que les pêcheurs écoutent sur les motifs de l'ODEC en matière de conservation. Il est important de maintenir un dialogue régulier avec les pêcheurs et d'avoir des processus transparents et bien documentés qui démontrent l'équité sociale. Grâce aux nombreux programmes d'éducation à l'environnement mis en place par l'ODEC au fil des ans, et grâce à ce programme, les pêcheurs ont la possibilité d'en apprendre davantage sur l'écosystème et, en fin de compte, de décider eux-mêmes s'il est important de bien gérer leur écosystème et de soutenir la conservation.

Renforcer la capacité d'action collective et de prise de décision éclairée

Les communautés de pêcheurs du corridor sont isolées les unes des autres et marginalisées par rapport à l'économie régionale. Elles ont peu d'occasions d'interagir à cette échelle. Même au sein d'une communauté, la structure sociale est faible. Le projet a créé un forum d'interaction et de collaboration pour résoudre les problèmes. Pour renforcer la capacité à participer à ce forum et au processus de planification, nous nous sommes concentrés sur le renforcement de la capacité des pêcheurs à représenter leurs communautés au sein d'un groupe de gestion intercommunautaire. Des ateliers ont été proposés sur la communication, la négociation et d'autres compétences de leadership. Nous avons élaboré des documents, organisé des ateliers et des échanges avec d'autres pêcheurs pour leur permettre de mieux comprendre la variété des outils de gestion qui peuvent être appliqués pour améliorer les pêcheries et réduire les conflits. Il s'agit là d'un élément essentiel pour préparer le terrain à une prise de décision éclairée et à l'adoption de nouveaux instruments de gestion. Pour que le processus soit mieux accepté, tous les membres de la communauté doivent être informés. Grâce à des programmes de communication, des messages sur des panneaux d'affichage, des messages radio, des médias sociaux et des ateliers, le programme implique l'ensemble de la communauté pour qu'elle comprenne et soutienne le processus.

Facteurs favorables

L'ODEC a une longue histoire de promotion de la culture environnementale dans la région et dispose d'outils et de ressources qui facilitent ce processus. La capacité de l'ODEC à communiquer dans une langue que les pêcheurs comprennent facilite l'apprentissage. En tant qu'organisation locale, la CEDO peut adapter le calendrier des réunions et des cours au rythme de la pêche, qui est quelque peu imprévisible en raison des conditions environnementales. Les pêcheurs et les communautés sont désireux d'apprendre, mais ne peuvent se permettre de manquer les revenus de la pêche.

Leçon apprise

L'un des défis est le transport. Les communautés sont isolées des transports publics et l'ODEC a tenté de les mettre en place, mais sans ressources suffisantes. Des solutions pourraient être trouvées si des fonds étaient disponibles pour acheter des camionnettes. L'un des éléments les plus importants pour un renforcement efficace des capacités est de parler la langue de votre public et de créer des expériences d'échange, plutôt que de parler au public. Cela crée un environnement d'apprentissage positif tant pour le facilitateur que pour les pêcheurs. Le renforcement des capacités est également renforcé par la participation directe et les opportunités d'apprendre en faisant, ce que nous promouvons comme un autre élément constitutif de ce processus.

Participation tout au long du processus

Ce projet implique les pêcheurs et d'autres acteurs dans la planification de leur utilisation future de la zone marine côtière du corridor de Puerto Peñasco, mais il cherche également à obtenir un engagement significatif des parties prenantes dès le début en les faisant participer à la mise en œuvre d'actions visant à améliorer la gestion de l'écosystème. De nombreux praticiens du CMSP sont frustrés par le temps nécessaire pour passer de la planification à la mise en œuvre, et les parties prenantes le sont également. Ce projet implique les parties prenantes dans des activités telles que le nettoyage des plages, la surveillance des ressources, l'analyse des données, la distribution de matériel à leurs communautés et le soutien aux jeunes de leur communauté. Il leur montre ce qu'est une action collective et comment elle peut être mise en œuvre de multiples façons. Il leur permet également de renforcer leurs capacités en matière de gestion des écosystèmes.

Facteurs favorables

L'OEDC participe à des programmes destinés aux jeunes et à d'autres membres de la communauté, tels que la surveillance des ressources et le nettoyage des plages, et nous menons d'autres activités pour impliquer les gens. Nous offrons aux parties prenantes la possibilité de s'impliquer dans des actions concrètes qui ont un impact immédiat sur leurs enfants, leurs plages et leur compréhension des ressources. Pendant que le long processus de planification se déroule, ces actions servent à inspirer les participants et à leur montrer ce qu'ils peuvent accomplir en participant et en travaillant ensemble.

Leçon apprise

Les pêcheurs ne comprennent pas le temps nécessaire à un programme de gestion intégrée. Ils sont impatients et veulent des résultats immédiats, c'est pourquoi il est important de les impliquer dans le travail qui doit être fait pour développer un système de gestion fonctionnel. Parfois, nous oublions de leur rappeler la vue d'ensemble et le calendrier qui montre où ils vont et ce qu'ils ont accompli jusqu'à présent.Ils craignent que le gouvernement ne fasse pas sa part dans ce processus. Maintenir l'engagement actif de tous les niveaux du gouvernement est essentiel, mais c'est aussi un défi, car les individus changent. Le gouvernement est constamment sollicité pour résoudre les problèmes à court terme plutôt que d'utiliser une approche plus globale et intégrée, et les pêcheurs doivent donc être encouragés à attendre. Il est important de créer des espaces permettant aux communautés de rencontrer le gouvernement. Le financement à long terme d'une telle approche globale et intégrée doit être garanti.

Intégrer les données scientifiques et les connaissances traditionnelles pour améliorer la gestion

L'écosystème du corridor a été bien étudié et plus de 200 000 points de données géoréférencées sont disponibles pour aider à établir des plans de gestion spatiale. Les communautés de pêcheurs ont participé à la surveillance des ressources par le passé et produisent actuellement des données sur leurs prises. Ces données, combinées à d'autres données issues de la littérature, d'entretiens et de processus de cartographie auxquels participent les pêcheurs, permettent d'intégrer un grand nombre de connaissances traditionnelles et d'informations scientifiques afin d'élaborer des propositions de gestion réalistes. Même lorsqu'on leur présente des analyses complexes de ces données résultant de modèles informatiques tels que INVEST et ZONATION, les pêcheurs font confiance aux informations qui leur sont présentées et les valident. En créant un processus de prise de décision qui utilise des preuves provenant de ces différentes sources et auxquelles toutes les parties prenantes croient, nous construisons un processus de prise de décision basé sur la science. Nous prévoyons de travailler avec les parties prenantes pour définir les meilleurs indicateurs permettant de suivre les effets de la gestion, puis de concevoir un processus participatif de suivi de ces indicateurs, en développant un langage commun, fondé sur la science, pour mesurer l'efficacité du programme. Le programme est en train de créer une plateforme numérique qui servira à communiquer les avancées.

Facteurs favorables

L'OEDC produit des données sur cet écosystème depuis 37 ans, ce qui permet d'intégrer la science dans le processus. La longue histoire de la participation des pêcheurs au suivi est également utile, car ils n'ont pas remis en question la validité des données qu'ils voient, en général, et ils ont également la possibilité d'affiner les résultats. La validation par le gouvernement des données générées est essentielle. Le gouvernement a contribué financièrement à la production des données et le travail de l'ODEC est connu et respecté.

Leçon apprise

Le financement du suivi à long terme est important et doit inclure les ressources nécessaires à la gestion et à l'analyse des données. L'implication des pêcheurs dans le suivi, le partage d'autres sources de données avec eux et la production de résultats cohérents avec leur compréhension de l'écosystème sont autant d'éléments qui leur permettent d'avoir confiance dans les résultats. Le programme implique également une équipe technique qui comprend le processus et participe à l'évaluation des éléments critiques de l'analyse. Le partage des résultats, des crédits et des publications avec les chercheurs du gouvernement peut constituer une incitation importante pour le gouvernement à collaborer à la production et à l'analyse des données.

Impacts

Les communautés de pêcheurs de ce corridor n'étaient pour la plupart pas organisées et n'avaient que peu d'expérience en matière de collaboration pour trouver des solutions. La participation active et continue des pêcheurs à l'amélioration de la gestion des ressources témoigne d'un impact positif. Ils ont conçu et adopté divers instruments de gestion de la pêche : 1) refuges de pêche (protégeant environ 5 % de la zone) ; 2) zones gérées localement (qui, même dans leur conception, renforcent l'intendance) ; 3) permis et 4) quotas de capture (ces deux derniers contribuent à contrôler l'effort de pêche et la surexploitation des ressources). Le processus est renforcé par des exercices réguliers de renforcement des capacités et des activités telles que le suivi et les ateliers de conception d'outils de gestion, en recherchant un engagement significatif des pêcheurs dans la planification de leur propre avenir. La création d'une structure de gouvernance avec les utilisateurs locaux au centre, où ils ont accès au gouvernement et aux scientifiques, crée un processus transparent qui aide à renforcer la confiance et la gestion du plan de gestion au sein des communautés et entre elles. Les solutions proposées se concentrent sur l'activité économique principale des pêcheurs, répondent à leurs besoins, aident à clarifier les droits et à réduire les conflits. Il est encore trop tôt pour évaluer l'impact de cette solution sur l'environnement, mais les instruments de gestion spatiale sont conçus pour améliorer les prises de pêche tout en assurant la protection des habitats et des espèces clés.

Bénéficiaires

La première phase du projet vise principalement les utilisateurs traditionnels : 1 076 petits pêcheurs de six communautés et 150 utilisateurs locaux de six zones humides sont les principaux bénéficiaires, mais le gouvernement et les scientifiques en profitent également.

Objectifs de développement durable

Histoire

En 1996, l'OEDC a réalisé la première évaluation de la pêche artisanale dans le haut golfe de Californie et c'est là que nous avons rencontré un groupe de plongeurs commerciaux qui s'inquiétaient de la diminution de leurs ressources. Le murex noir et la coquille Saint-Jacques étaient leurs pêcheries les plus importantes et nous avons donc travaillé ensemble pour créer des réserves volontaires et les surveiller. Nous avons élaboré un plan de gestion pour la coquille Saint-Jacques et les pêcheurs se sont vu accorder l'usage exclusif d'une sorte de zone de gestion locale. En raison de la nature de leur travail, la plongée, ils ont besoin de plus de cohésion et de coopération que les autres pêcheurs, et ce groupe était exemplaire. Ils ont reçu le prix national mexicain de la conservation en 2003 et, plus important encore, leurs ressources ont commencé à se reconstituer et ils sont devenus des adeptes convaincus des avantages potentiels des réserves marines ou des refuges. Cependant, malgré leurs bonnes pratiques de gestion, en 2012, de nouveaux pêcheurs sont arrivés dans la région et ont commencé à exploiter les ressources de plongée, les épuisant une à une, même sans permis. En tentant de faire appliquer la loi par le gouvernement, les plongeurs se sont retrouvés plus vulnérables. L'application de la loi est devenue le facteur limitant et il est devenu évident que leur appel à l'aide ne serait pas entendu à moins que nous puissions attirer l'attention du gouvernement, à une échelle qu'il écouterait. Il était également clair que nous devions impliquer les parties prenantes qui prenaient illégalement les ressources sans se préoccuper de la gestion durable. Cela nous a permis de définir un nouveau champ d'application pour la gestion de la pêche, qui engloberait tous les utilisateurs d'une zone définie. Nos recherches nous ont permis d'identifier cette zone et les communautés concernées. Il a été difficile d'impliquer les six communautés du corridor, car elles n'étaient pas du tout organisées et beaucoup d'entre elles n'avaient pas de permis, mais elles comprenaient que cela les rendait vulnérables. Grâce à de nombreuses heures d'ateliers, de discussions et de planification, la dynamique a changé et de nombreux pêcheurs sont devenus des porte-parole convaincus de leur participation à l'amélioration de la gestion. Une fois que les instruments de gestion seront formalisés et mis en œuvre, les impacts positifs sur l'environnement seront transparents pour tous, ce qui scellera le soutien d'un plus grand nombre de parties prenantes de la région dans ce processus d'auto-gouvernance.