Sound legislative governance framework for spatial planning and management

Solution complète

Most of the islands in the GBR do form part of the World Heritage Area but the federal Marine Park does not extend above the low water mark.

This solution addresses the complexities of having multiple jurisdictions and interests involved in co-managing a very large and diverse area. Today complementary management and planning provisions apply in virtually all marine waters within the GBR, irrespective of the jurisdictional responsibility.

Dernière modification 28 Mar 2019

5425 Vues

Contexte

Challenges addressed

Managing an MPA when jurisdictional and ecological boundaries do not align. Effectively managing a large area can be jurisdictionally complex; e.g. within the GBR, some areas are managed by the federal government, some areas are managed by the State of Queensland, and other areas have been recognised as being sea country for specific Indigenous owners. Various ways have been developed to maximize complementary planning and management while minimising public confusion.

Emplacement

Great Barrier Reef, Queensland, Australia

Oceania

Traiter

Summary of the process

Collectively these building blocks outline how a sound governance framework has developed over the years to manage such a jurisdictionally complex area as the GBR. This includes a strong commitment to effective and meaningful partnerships with Indigenous people, local communities and industries to help conserve the values of the GBR.

One of the key building blocks is the cross-jurisdictional agreements outlined in BB1 between the Australian government and the State of Queensland. These agreements are implemented by the complementary management approach which includes the complementary legislation as outlined in BB2.

Australia also has international obligations as outlined in BB3, some of which flow down into national legislation.

Three other key aspects of the shared governance approach are also outlined:

- BB4 explains how the Indigenous Traditional Owners work with both levels of government to manage what they consider is their sea country;

- BB5 outlines various advisory committees (both voluntary and appointed) that assist the GBR managers, ensuring a range of public input occurs; and

- BB6 explains how major industries, along with key groups such as councils and schools , work in on-going partnerships with governments.

Building Blocks

Cross-jurisdictional agreements

There is a strong and long-standing working relationship between successive Australian and Queensland governments for the protection and management of the GBR. This was first formalised in 1979 through the Emerald Agreement signed by the (then) Prime Minister of Australia and the (then) Premier of the State of Queensland. This Intergovernmental Agreement (IGA) provides a clear and effective framework for facilitating cooperative management of the GBR, with the commitments of both governments detailed in schedules which help to implement the IGA.

The IGA was updated in 2009 to provide a more contemporary framework for cooperation, recognising challenges that were not foreseen in 1979. Through implementation of the IGA, both governments have agreed and are delivering a joint program of field management, joint action to halt and reverse the decline in the quality of water entering the GBR, and action to maximise the resilience of the GBR to climate change.

The joint development of the Reef 2050 Plan in 2015 led to the IGA being updated to reflect the shared vision outlined in that plan, and renewed both governments’ commitment to protecting the GBR World Heritage Area including its outstanding universal value.

Enabling factors

• The fact that the initial agreement in 1979 was signed by the (then) Prime Minister and the (then) Premier of Queensland gave that Agreement, and all subsequent agreements, considerable force and credibility.

• The requirement in the IGA that the GBR Ministerial Forum must meet at least annually helps to oversee implementation and ongoing monitoring of the IGA and the Reef 2050 Plan.

Lesson learned

1. It is important to periodically review and update such intergovernmental documents. The 1979 Agreement was updated in 2009 and again in 2015 to provide a contemporary framework for cooperation between both governments, recognising challenges such as climate change and catchment water quality that were not foreseen at the time of previous IGAs.

2. Implementation of the IGA is overseen by a GBR Ministerial Forum, consisting of relevant Australian and Queensland government ministers; this ensures an integrated and collaborative approach by the Australian and Queensland governments to the management of marine and terrestrial environments within and adjacent to the GBR World Heritage Area.

3. The Reef 2050 Plan, now a formal schedule to the IGA, includes a commitment from both governments to work together on GBR management and continue collaborative efforts with industry, science, traditional owners, conservation organisations and the broader community to improve the health of the GBR.

Complementary legislation

Complementary legislation refers to laws that complement or supplement each other, applying matching or ‘mirrored’ provisions to enhance public understanding or enhance the mutual strengths of the laws.

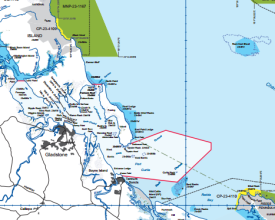

The reasons why complementary management is essential in the GBR is outlined under ‘Impact’ for this Blue Solution, including the fact that the State and federal governments cannot agree where the boundary occurs between their respective jurisdictions.

The Zoning Plan for the federal Marine Park was revised from 1999-2003 and came into effect on 1 July 2004. To ensure complementarity and to minimise public confusion, the State of Queensland declared the Great Barrier Reef Coast Marine Park in November 2004. The zoning for this Coast Marine Park mirrors the adjoining federal zoning by providing complementary rules and regulations between high water and low water, all along the mainland adjoining the GBR and around all Queensland islands within the outer boundaries of the federal Marine Park.

Complementary zoning means that activities that can be undertaken within the two Marine Parks are governed by the same regulations; however, there are also some Queensland specific provisions that may apply only in the GBR Coast Marine Park.

Enabling factors

• The Australian Constitution states when a State law is inconsistent with a federal law, then the federal law shall prevail; the State law is, to the extent of the inconsistency, invalid.

• Section 2A(3f) of the GBRMP Act requires “... a collaborative approach to management of the GBR World Heritage area with the Queensland government”.

• The 1979 intergovernmental agreement agreed on a complementary approach which subsequently aided the evolution of effective complementary legal instruments.

Lesson learned

• Complementary legislation ensures a workable solution so that all marine waters seaward of the Highest Astronomical Tide are effectively under the same rules and regulations, irrespective of the jurisdiction in which they occur.

• Using complementary legislation for policy is far more effective than having slightly differing interpretations for adjoining areas or similar provisions drafted in a way that allows differing interpretations.

• A complementary approach is more holistic and effective for the following reasons:

- ecologically: it recognises temporal/spatial scales at which ecological systems operate (rather than the inadequacies of jurisdictional boundaries)

- practically: it is easier to manage, ensuring that matters do not slip through ‘unforeseen regulatory cracks’; and

- socially: it helps with public understanding and hence compliance.

• To ensure a complementary approach, officers in both governments cooperate when developing policies.

Relevance of international conventions for MPA management

Australia is a signatory to a wide range of international conventions/frameworks relevant to MPAs; the main ones are listed in Resources below and include global and regional conventions and treaties as well as bilateral agreements.

The fundamental basis for international law and conventions is mutual respect and recognition of the laws and executive Acts of other state parties.

• Note the term ‘state party’ is used in many international conventions instead of ‘nation’ or ‘country’ – but don’t confuse the term with federal states or territories.

Some of the obligations arising from these international conventions have been incorporated into Australian domestic law (e.g. some provisions of key international Conventions addressing significant matters such as World Heritage, are incorporated into Australia’s national environmental legislation, the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999).

How much international conventions impact on various countries will vary according to the regulatory, legal and political context of the country in question, whether that country is a party to the relevant conventions or agreements, and whether these have been implemented at the national level.

Enabling factors

• The range of international instruments, in conjunction with domestic (national) legislation and to a lesser extent, Queensland (State) legislation, collectively give the GBR very strong legal protection.

• International law may be relevant to interpreting domestic (national) legislation and may assist if there is an ambiguity in domestic law.

Lesson learned

• Once a country has signed and ratified an international convention, there are international obligations with which that country must comply; however, enforcement of non-compliant nations by the global community is not easy.

• The level and detail of reporting on international obligations varies; some examples are shown in ‘Resources’ below.

• The ‘precautionary approach’ has become widely accepted as a fundamental principle of international environmental law and is now widely reflected in Australian environmental law and policy.

• Some of the issues facing coral reefs, such as climate change, are global or trans-boundary and are addressed in international conventions – however while those issues may be global, many also require local level solutions for effective implementation.

Resources

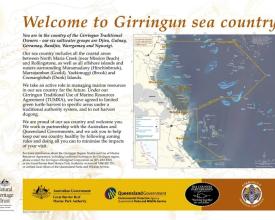

Co-managing with Indigenous Traditional Owners

Aboriginals and Torres Strait Islanders have been the Traditional Owners (TOs) of the GBR for >60,000 years. Today traditional customs and spiritual lore continue to be practised by 70 TO clan groups whose sea country includes the GBR. The TOs continuing social, cultural, economic and spiritual connections to the area is acknowledged by the park managers (GBRMPA).

An Indigenous Partnerships Group in GBRMPA works closely with TOs to establish meaningful partnerships to protect cultural and heritage values while conserving biodiversity. One way is a management arrangement called a Traditional Use of Marine Resources Agreement (TUMRA), a formal agreement for sea country developed by TO groups and then accredited by both GBRMPA and Queensland. Another is an Indigenous Land Use Agreement (ILUA).

There are currently seven TUMRAs and one ILUA accredited in the GBR which collectively involve 15 TO groups and cover 22% of the GBR coastline. Each TUMRA operates for a set time after which it is renegotiated.

Indigenous engagement in the GBR is fostered by membership on the Authority Board, an Indigenous Reef Advisory Committee, compliance training and management workshops for TOs, and the use of traditional ecological knowledge.

Enabling factors

• Having definitions and processes set out in the legislation was invaluable, for example:

- Section 3 of the Act defines a ‘traditional owner’

- S. 10 (6A)) requires a member of the Board to be “an Indigenous person with knowledge of, or experience concerning, indigenous issues relating to the Marine Park”

- S. 2A (3e)) requires a “partnership with traditional owners in management of marine resources”

• The GBR Regulations defines how a TUMRA is to be made, accredited, terminated, etc.

Lesson learned

• Experience shows an effective format for a TUMRA has three parts:

1. A narrative outlining the TOs aspirations for their sea country;

2. Specific details e.g. the areas in which traditional activities, such as hunting, will, and will not, occur or are limited by the TUMRA.

3. An implementation plan (e.g. outlining ways the TUMRA will educate the public and other TO groups about their sea country).

• Compliance training for TOs has not only led to an increased awareness of marine compliance issues, but more importantly, to an increased feeling of empowerment by TOs to manage their sea country.

• Managers should not expect that one Indigenous representative is able to speak on behalf of all Indigenous people or that the best way to engage TOs is the same as for other users or stakeholders.

• Recognize different knowledge systems, and consider traditional ecological knowledge as complementary to western science.

Multi-sectoral Advisory Committees

3 different types of advisory committees support the management of the GBR, each with differing responsibilities:

• Local Marine Advisory Committees (LMACs): community-based committees at 12 major towns along the GBR coast. They provide a two-way flow of information between the community and the GBR managers, and advice at the local level. Managers are required to attend all meetings to hear community views and discuss local marine/coastal issues. LMAC members are voluntary and may represent a community or industry group or be independent.

• Reef Advisory Committees (RACs): expertise-based RACs provide expert-advice for critical issues facing the GBR (such issues as catchment and ecosystem management; Indigenous Partnerships; and tourism/recreation). RAC members are appointed for a three year term from stakeholders with expertise and experience in the critical issue. RACs meet formally with GBRMPA officers 2-3 times per year to assist in developing policy and provide strategic advice for GBR management; RAC Chairpersons also meet periodically with the GBRMPA Board.

•Reef 2050 Advisory Committee: formally advises the GBR Ministerial Forum, including strategic advice about implementation of the Reef 2050 Plan and GBR management.

Enabling factors

• Having a clear objective in the Act that encourages “… engagement in the protection and management of the GBR by interested persons and groups, including Queensland and local governments, communities, Indigenous persons, business and industry” has proven to be very beneficial (see Section 2A (2b)).

• A comprehensive Charter of Operations provides clear guidance as to how LMACs and RACs must operate.

Lesson learned

• The three differing types of committees cover a broad range of technical and geographical advice, thereby strengthening the overall legitimacy of that advice.

• A member of the GBRMPA Senior Management Team is allocated to each LMAC and must attend meetings with the dual aims to build rapport with the locals and report back to senior management.

• An independent Chair for each RAC and LMAC is appointed by the GBRMPA Chairman to help ensure effective committee meetings and outcomes.

• An annual meeting of all LMAC Chairs has proven useful for cross-fertilization of ideas and to facilitate interaction between the 12 LMACs.

• Sitting fees are not paid to any members to attend these committees; however, travel costs are covered for members to attend RAC and Reef 2050 meetings.

• Minutes of RAC meetings are not for public distribution; however a summary report is publicly-available after each RAC meeting summarising the major items discussed at the meeting (see ‘Resources’ below).

Resources

Partnerships with key sectors to enhance management efforts

A range of partnerships have been established to assist with GBR management efforts; these include:

-The Reef Guardian Schools (RGS) program began in 2003. Today it involves >120,000 students from 276 schools (i.e.10% of the entire population of the GBR catchment undertake stewardship programs as part of a RGS).

-The RGS initiative was expanded in 2007 to include Reef Guardian Councils (i.e. local government councils). Currently, 16 councils along the GBR Coast demonstrate their commitment to improve the health and resilience of the GBR through such actions as sewerage treatment, storm water treatment, waste reuse/recycling and community education.

-In 2010 the program was again expanded to include Reef Guardian Farmers and Reef Guardian Fishers. While still only pilot programs, the Fishers and Farmers programs help promote other initiatives being undertaken by these industries while also delivering environmental benefits.

Other partnerships include:

-The marine tourism industry is a key partner in GBR management, enhancing visitor experiences and helping to protect the biodiversity that supports their industry.

-The GBR aquarium supply fishery developed a world’s-first Stewardship Action Plan including collection standards

Enabling factors

• One object of the GBRMP Act is “encourage engagement in the protection and management of the GBR by interested persons and groups, including … communities, Indigenous persons, business and industry” (s. 2A (2b)).

• Article 5 of the World Heritage Convention obligates nations who are signatories to the Convention, ”… so far as possible… to adopt a general policy which aims to give the cultural and natural heritage a function in the life of the community …”.

Lesson learned

• Getting local communities involved in GBR protection and management, and developing partnerships with schools, councils and industries are some of the real success stories in the GBR.

• All the Reef Guardian initiatives have created awareness, understanding and appreciation by various industries that depend on a healthy GBR.

• There is no doubt that an informed and involved community fosters stewardship and promotes a community culture of custodianship for GBR protection.

• Successful engagement is dependent on the willingness of the community members and stakeholders to engage on matters that are important to them, and on the level of commitment of managers to also get it right.

• There is a wealth of relevant expertise in local communities – the challenge is how to harness that in an on-going way.

• High Standard Tourism Operators voluntarily operate to a higher standard than required by legislation as part of their commitment to ecologically sustainable use.

Resources

Impacts

The most significant impact of complementary management is that the boundary between the State and federal waters does not need to be defined nor mapped. The same rules and regulations effectively apply either side of the boundary, i.e. all waters seaward of the high water mark, extending to the outer (seaward) edge of the federal Marine Park.This resolution also addresses the fact there are ~1,000 islands with the Park’s outer boundary, all surrounded by tidal waters. Furthermore there are differing jurisdictional interpretations of where low water mark (LWM) occurs. LWM also periodically moves because of erosion and accretion, so mapping the boundary is impractical. This issue would be further complicated given there are no clear or agreed principles for defining what are ‘the internal waters’ of the State i.e.which parts of bays, channels, river mouths or estuaries are ‘internal waters’ and hence not part of the federal Marine Park. Finally, the complementary approach is a workable solution providing far more effective management; e.g. LWM is frequently covered by water, making it unworkable as a boundary from an enforcement perspective. Management would be much more complicated if the rules were different in each jurisdiction

Beneficiaries

Both the managers of the GBR as well as the public who need to understand which rules apply where.

Story

Most people are aware that the GBR covers a very large area (a similar area to Italy or Japan). Few, however, are aware of the jurisdictional complexities that occur within that large area and the implications for governance.

Within the GBR World Heritage Area, four layers of legislation apply:

• international law (see BB3 - ‘Conventions’);

• Commonwealth law (i.e. law enacted and administered by the Australian Government);

• Queensland law (including planning schemes and local laws made by local governments); and

• common law (i.e. law developed by judges in courts) – in Australia, Native Title, now recognised as part of the common law, has important implications for environmental law.

The Australian Constitution establishes the overarching legal authority for environmental management, with responsibility shared between the federal and State governments.

Various tools have evolved over 40 years to address these jurisdictional complexities, with the overarching aim to protect, conserve and manage the GBR. These include a formal Intergovernmental Agreement that provides the basis for cooperative arrangements between the Australian and Queensland governments.

The federal GBR Marine Park covers the majority of the waters within the outer GBR boundary. However, that Park does not include any tidal lands/tidal waters along the mainland coast or around islands, nor 13 coastal exclusion areas around major ports, nor the majority of the ~1000 islands, nor any ‘internal waters’ of Queensland (see ‘Impacts’ above for ‘internal waters’).

Most of the islands within the GBR are under Queensland jurisdiction (only 70 islands or parts of islands are under federal jurisdiction as they contain lighthouses or defence training areas). About half of all the GBR islands are declared as ‘National Parks’ under Queensland legislation; the remainder are a mixture of tenures including freehold, leasehold, unallocated State land and Aboriginal land.

To further complicate matters, the GBR World Heritage Area covers a slightly larger area than the federal Marine Park – the World Heritage Area includes all 1000 islands within the outer boundaries and all waters seaward of low water mark including any waters in the ports or within internal waters of Queensland below LWM.

Today the complementary management approach means that all marine waters within the GBR, irrespective of the jurisdictional responsibility, have virtually the same rules and regulations.