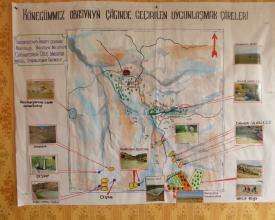

Sustainable land use management in Konegummez village, Turkmenistan

Konegummez village is located in the southwestern part of the Kopetdag mountains of Turkmenistan, bordering with Iran, at an altitude of 1,350 meters above sea level. The village hosts 200 families, with a population of about 1,229 people who live in a semi-arid climate and make their living by livestock keeping and agriculture, mainly.

Based on the villagers’ social strengths and will and supported by international development projects, nowadays the village is an excellent example for collectively planning and managing natural resources and agriculture with improved ecosystem services and biodiversity whilst generating income in a sustainable way.

In the following, the social, organizational and technical issues which led the Konegummez community to having success, will be described.

Contexte

Challenges addressed

Konegummez village is situated in a semi-arid climate in mountain areas. Water has always been a scarce resource, as well as fertile soil for agriculture.

Due to sharp population and livestock number growth, the natural juniperus forests of the area, protecting soil and providing water have been degraded. Also, natural pastures have been degraded significantly. In 1930, about 150 dwellers lived in the village with 800 heads of small ruminants and 100 heads of cattle. Cat present, 1,229 people live in the village owning a total of 5,000 heads of small ruminants and 700 heads of cattle.

Under these conditions, the local population had to look for ways to sustainably manage pastures, conserving and restoring remaining forests, develop water harvesting techniques and look for other income sources.

Emplacement

Traiter

Summary of the process

All building blocks are part of one sustainable and integrated land use management approach. On the one hand, there are ‘hard’ components, like BB1, BB2 and BB3, focusing on natural resource management, agriculture and animal husbandry. On the other hand, there are ‘soft’ dimensions of the approach, related to peoples’ behaviour, interactions and social-cultural relations.

The ‘hard’ components do not work without the ‘soft’ components. Successful land management approaches are implemented by well-organised, motivated and keen to learn people. People and their social-cultural interactions are the foundation.

Building Blocks

Sustainable water harvest and management in semi-arid areas, including natural resource protection

Water for household consumptions as drinking water, as well as for irrigation in agriculture and for watering livestock, is a basic and scarce resource in rural areas of Turkmenistan. Thus, in semi-arid climate, water is a strong driver for development and sustainable land use management.

In 1991, Konegummez villagers were able to build their own water supply system. One person was appointed as mirab (a person responsible for equitable distribution of water and monitoring of irrigation schedules) for further technical maintenance of the system.

In addition to this, with the participation of international development organisations, in 2006 villagers constructed a water well for supplying water to new agricultural land for growing fruit trees and vegetables.

To date, the village owns 4 water wells and 5 catchment dams have been built, where reservoirs with large volumes of water have been formed. These reservoirs not only supply people with water, but also serve as a watering point for livestock.

In order to protect water sources in the in vicinity of the village, villagers planted 10,000 juniper trees. On these conservation sites, grazing of livestock is strongly controlled. The measure went hand-in-hand with reducing the number of livestock significantly.

Enabling factors

Due to strongly growing population and growing number of livestock, villagers were urged to look for solutions related to water provision. Based on the clear articulation of their needs and contributing own resources, villagers were able to get the support of government organisations, as well as of international development cooperation for water harvesting and management measures.

Lesson learned

The major lesson learnt was that water harvest and management cannot be handled as an isolated issue. It is interwoven with landscape level protection and restoration of natural resources, like natural forests, as well as with managing productive land for agricultural and livestock purposes. Only if these measures are planned and managed in combination, water harvest and management will be successful.

At a technical level, lessons-learnt are related to the need to establish water wells and harvesting surface water in reservoirs, for providing sufficient water for a growing population, and livestock and also diversified agricultural production.

Intensifying and diversifying agricultural production

In Konegummez the availability of fertile land is limited. Farmers are growing vegetables, such as tomatoes, carrots, cabbage or potatoes. Almost every family owns fruit trees, e.g. apple, apricot, walnut and almond. Harvest is used for family consumptions first and the surplus is stored for the winter.

In 2014, local farmers with support of a project built the first greenhouse (90 m²). The leader and elder of the village were appointed with the responsibility to manage the greenhouse. The purpose of the construction of this greenhouse was to train local farmers and thereby adapting to negative impacts of climate change. The following year, three more greenhouses were built by farmers on their own.

On a leased field plot of 33 ha farmers grow fruit trees and vegetables. More than half of the harvest is sold. The plot is irrigated by drip irrigation, what ensures a very low water consumption.

On individual leased rainfed fields, farmers grow wheat by government order. On these plots, the income from farming depends on the level of precipitation and, thus, varies widely from year to year.

In general, over the last 15 years, farmer families have diversified their agricultural production significantly and made it more resilient to the negative impacts of climate change.

Enabling factors

The initial support by an international development project for the greenhouse was very helpful as for providing innovative technology in this area. The management by and worthwhile prove of the greenhouse, as well as different, new forms of vegetables, was a very important factor for farmers gaining trust in the new technology. The successful sale of vegetables and fruit on nearby markets, is an important incentive for farmer families.

Lesson learned

Diversifying agricultural production at a larger scale (in this case village level) depends on people interested to try out something new. In the case of Konegummez, the elder and village leader acted as ‘innovator’. This fact combined 2 success factors: (1) willingness to try out new things and (2) having a person as ‘innovator’ who is socially accepted, even better in a higher hierarchical position, as in this case the leader.

For cost-intensive innovations, as the greenhouse, it also seems important that an actor, in this case the international development project, who can provide financial resources, takes the risk related to possible failure. This significantly contributes to poor farmers engaging in innovative technologies.

Sustainable pasture and livestock management

The main income source of farmers is livestock. Every year, when the number of small ruminants has increased, sheep are sold at the market place or used for consumption purposes, to maintain the carrying capacity of natural pastures. The sale of sheep is mainly done in summer. For personal use, animals are slaughtered in the fall, and canned as stocks for consumption until next fall. At present, there are 4 herds of small ruminants in the village, with a total of 5,000 heads, and 700 heads of cattle.

In addition to meat products, farmer families generate small income from producing local cheese (cow and goat). Recently, the demand for goat cheese has increased by people from the regional city centers traveling to the village.

Recently, animal owners reduced by 30% (from 7,500 to 5,000) the number of small ruminants in their herds. The number of animals is controlled by bayars (elected farmers who have extensive experience in livestock keeping). Bayars check the number of animals every two months and warn the animal owners to reduce the number of livestock if the herd exceeds 1,000 heads. At the end of each season, farmers sell their animals to reduce the herds to 800 heads. Farmers also began to improve the breed of cattle, hardy to the harsh cold of the highlands.

Enabling factors

In livestock farming societies the number of livestock is not just an economic issue but also one of social status. High number of livestock means high social status. Konegummez farmers overcame this social trap, which leads to degradation of natural resources. Local farmers have developed a mechanism (the so-called bayar) which enables by mutual agreement to maintain a livestock number that responds to the carrying capacity of pastures. The better quality of tsheep leads to less susceptibility to diseases and better market prices.

Lesson learned

Changing animal husbandry patterns is a big challenge in livestock farming societies. It calls for widespread social agreements within the society, backstopped by the community’s leaders and will only work, if:

- farmers have a clear, tangible benefit by reducing livestock number;

- there are clear, mutually agreed mechanisms in place to control livestock number.

Joint planning and collective action at community level

The development of Konegummez is characterized by strong collective action. By organizing themselves, the community members have achieved to encourage government agencies to provide basic services as, for instance:

- 1940s to 1960a: school, post office, library, grocery store, electricity and the first water well were established.

- 1999 the village was gasified and 2016 the villages access road was asphalted.

- Villagers built 3 large bridges themselves.

In the 2000s, in order to sustainably manage natural resources and handling other issues of the community, an informal committee was formed, including 9 villagers. The group learned to identify community challenges and solutions and how to develop action plans. Each year, the group develops an annual action plan, which is socialized and finally agreed on with the villagers. There is also a long-term planning, focusing on bigger issues.

After having performed a large amount of social and environmental protection work in the community, there is an understanding of villagers to continue solving problems by joint efforts. Community leaders have emerged who have the trust of the villagers. There is also mutual understanding with local authorities and government organisations, the latter supporting villages in tackling their challenges.

Enabling factors

A great contribution to the development of self-organization of the local community was made by development projects. Villagers not only received financial support, but also developed knowledge and skills in planning, leadership development, building social partnership, sustainable pasture management, climate change adaptation, etc. Nonetheless, the people of Konegummez already had the ‘spirit’ to learn and made in the past good experiences with planning, organizing and implementing community work together, the so-called ‘strength-of-unity’.

Lesson learned

According to villagers, international projects have helped them to look at the world from a different perspective, to broaden their horizons, to unite even more, to raise funds and resources for sustainable rural development. Most of the committee members were able to visit Israel, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan and Turkey and exchange experiences and new knowledge and pass them on to their fellow villagers.

This knowledge they use now to sustainably manage natural resources and to protect and rehabilitate their forests.

Combining traditional social cohesion with new forms of local organisation

Konegummez is provided with many domestic services and ecosystem services from natural resources. During the second world war, the villagers, unlike others, did not starve; diligence, mutual assistance, organization, as well as hard working and love for their land helped them to survive in difficult times.

Since the foundation of the village, the dwellers have continuously engaged in collective action, based on mutual trust and the believe ‘together we are strong’. Over time, the strong social cohesion has also ‘paid’ for the villagers. These positive experiences fortified the believe ‘together we are strong’ and motivated villagers to always aspire new horizons and to develop their village further.

That was also the reason why they were able to build an informal committee in order to sustainably plan and manage natural resources in the village. The group includes a total of 9 people: shepherds, bayar, village elders, mirab, farmers and one teacher.

Another example for ‘modern’ organisation is related to the sale of agricultural products. Farmers have developed a resource-saving mechanism. They choose from their own villagers one person with a small truck, who goes to the market and sells the harvest of several farmers there. From the income received, each farmer pays 10%.

Enabling factors

As emphasized above, the most important enabling factor for social cohesion and well-working local organisation is the success achieved by the villagers by organising themselves. It is a really strong driver for sustainable development.

Lesson learned

Social cohesion, mutual trust and strong leadership are the pillars for sustainable rural development and can be utilized irrespectively of the issue at hand in different contexts: e. g. infrastructure improvement, local economic development and sustainable use of natural resources.

Impacts

Sustainable land use management calls for integrating social-cultural, ecological, economic and technical aspects, in order to be successful. The Konegummez village is an excellent example of how integrating these elements can work in practice.

The villagers have been able to:

- Combining traditional forms of local organisation, as bayars (elected residents who have extensive experience in animal husbandry) who control livestock number and new informal committees for collectively planning pasture management and natural resources conservation.

- Consciously and collectively planning the use and management of natural resources and agriculture, based on agreed and written planning, followed by monitoring.

- To restore and protect natural pastures against degradation, by farmers reducing their livestock by 30% (from 7,500 to 5,000 heads of small ruminants) to a sustainable level.

- Engaging in alternative, for the area innovative forms of agriculture, as, for instance, vegetables grown in green houses growing fruit trees with irrigation, intensifying and concentrating agricultural production on smaller plots of land.

- Sustainable water harvesting and water management: construction of 4 water wells 130-140 meter depth and 5 catchment dams, where reservoirs with large volumes of water have been formed and reforestation by planting of 10,000 juniper seedlings on mountain slopes.

Beneficiaries

Beneficiary of the land management measures developed is the entire population of Konegummez village, whose main income sources are livestock keeping and agriculture.

Sustainable Development Goals

Story

In 2014, in the village, local farmers with support of an international development project built the first greenhouse with a base area of 90 m². At the general meeting of the village, it was decided to appoint the village leader and elder of the village, who enjoys great respect among the population, with the responsibility to manage the greenhouse.

The purpose of the construction of this greenhouse was to train local farmers in the special features of growing crops in greenhouses, thereby adapting to the negative impacts of climate change and reducing possible risks associated with. According to the elder, in the first year bell pepper, chili and tomatoes were grown in the greenhouse. The elder distributed the harvest free of charge to the locals. When asked why he did so, he replied that at his age he does not need material wealth, for him the most important wealth is the well-being of his fellow villagers. If the residents understand that building a greenhouse is important, then they will start building greenhouses by themselves and thereby ensure the economic well-being of their families and their fellow villagers by providing affordable and healthy products. A year after the first harvest of the first greenhouse, three more greenhouses were built in the village and several more residents began to visit the elder for consultation.