Building Climate Resilience of Urban Systems through Ecosystem-based Adaptation (EbA) in Latin America and the Caribbean

CityAdapt promotes climate resilience in urban areas through the implementation of Nature-based Solutions (NbS) for adaptation. CityAdapt strengthens the technical capacities of municipalities, policymakers, and citizens to analyze the impacts and vulnerabilities to climate change and identify appropriate nature-based solutions for urban planning. The project’s goal is to reduce the vulnerability of urban communities to current and future effects of climate change (flooding, drought, landslides, etc.) by mainstreaming urban Ecosystem-based Adaptation (EbA) in city planning. It is carrying out EbA activities in urban areas and surrounding watersheds of Xalapa, Veracruz, Mexico; Kingston, Jamaica; and San Salvador, El Salvador. These activities consist of the restoration of mangroves, forests and riparian areas, implementation of climate-smart agriculture, construction of water retention structures, establishment of community gardens, and installation of roof rainwater catchment systems, among others.

Context

Challenges addressed

The three countries are extremely vulnerable to climate impacts. More hurricanes strike the region every year and with greater strength and more rain, which leads to flooding, landslides, loss of life and, of course, major economic damages, especially along the coast where tourism is strong, and many people live. Many countries are facing more severe droughts, punctuated by intense rains over short periods, representing a trend of increasingly erratic precipitation patterns. Drought combined with intense rains exacerbates environmental degradation related to deforestation and eroded soils. Climate impacts are especially dire in terms of economies, as a large percentage of the population works in rainfed agriculture. This has led to social challenges, including community instability with many people migrating to slums in urban areas without basic infrastructure and higher crime rates. Likewise, many also make dangerous trips northward to the United States.

Location

Process

Summary of the process

Firstly, the gender-differentiated vulnerability assessment (block 1) helps identify key areas and sectors of the population to target with NbS. As it is a participatory process, it helps build the capacity, relationships and coordination across community stakeholders and government agencies needed for implementation and ownership. The actual implementation of Nature-based Solutions (block 2) creates tangible benefits in terms of livelihoods and reduced risk of climate change induced disasters (flooding and landslides) as well as water scarcity. Learning activities such as workshops during and after implementation, cost-effectiveness analyses, monitoring of project activities and knowledge dissemination via demonstration sites and communications products (block 3) help to spread learning about the project and encourage its further integration into city planning and replication elsewhere.

Building Blocks

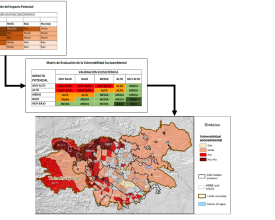

Building block 1: Gender-differentiated vulnerability assessment

This vulnerability assessment methodology allows for the accurate targeting of nature-based solutions to critical areas of need in cities and sectors of the population. It specifically includes a gender focus to ensure that adaptation efforts take into account how climate change affects women differently than men, given their varying roles in society. The vulnerability studies allow identifying the areas of greatest danger from weather-related events (such as landslides, floods, etc.) based on the exposure, sensitivity and adaptive capacity of the analyzed territory. They are carried out through participatory processes with communities and key stakeholders and climatic scenarios that integrate climatic, environmental and socioeconomic variables at the same time. The analysis also allows estimating the risk of loss of ecosystem services and therefore the potential needs for adaptation to climate change. This exercise is the basis for designing and implementing nature-based solutions to strengthen the resilience of communities in urban and peri-urban systems. Finally, this process builds a sense of co-ownership and relationships for partnerships to carry out the project.

Enabling factors

One of the main conditions needed for this building block’s success is the inclusion and approval of local communities and key stakeholders within those communities and their respective governments. Additionally, strong sources of climate and hydrological data facilitate this analysis process greatly.

Lesson learned

A key aspect of this block is access to data. For example, Mexico has abundant meteorological and hydrological data while El Salvador does not. This allowed for a much more thorough climate change scenario in the former case. In terms of the consultation process, capturing perceived risk, in addition to modeled risks, is key for developing targeted activities where they are most needed. In that process, including women through the gender-differentiated approach also contributes to better targeted adaptation efforts by successfully identifying socially vulnerable populations. During this vulnerability assessment, capacity building is essential to ensure that communities and policy makers can interpret and use the assessments subsequently.

Resources

Building block 2: Nature-based Solutions for Adaptation via Sustainable Livelihoods and Green Infrastructure

The Nature-based Solutions themselves are a core building block of the project. These solutions include reforestation, riparian restoration and infiltration trenches, the establishment of lineal, permeable trails for improved watershed functioning to reduce the risk of flooding and landslides during heavy rains, and water scarcity during dry periods. The tangible co-benefit of these measures is the reduction of disaster risk and easier access to water supplies, to name just two.

An integral part of these Nature-based Solutions is the creation of sustainable livelihoods that take pressure off ecosystems, including edible mushroom cultivation, beekeeping, urban agroforestry and gardening. The presence of these activities not only helps with decreasing pressure on ecosystems but also creating buy-in on the part of communities; they see a tangible economic benefit from the project and thus have a vested interest in its success. For example, mushroom cultivation has led to an additional source of income of $152 USD per month per plot for Xalapa households.

Enabling factors

The inclusion of key community and government stakeholders is crucial for this building block’s success, in addition to the physical space and coordination among differing agency mandates needed to implement NbS on a scale that will lead to tangible benefits.

Lesson learned

Identifying “hotspots,” or the most vulnerable areas of the community to implement NbS has been crucial to make the largest, and most visible, impact possible to prove the effectiveness of such solutions to the community. The project’s watershed perspective has also been critical for success, as it captures the ecosystem services (water infiltration) even when they extend beyond municipal limits to other jurisdictions. Community involvement is key to help avoid “maladaptation” or livelihood activities that will not be useful to communities or even add to existing problems (for example, crops that are not suited to a region’s soils), especially if there is a lack of interest or buy-in to continue them after the project has ended. Fruit trees and community gardens, for example, have proved to be successful sources of alternative livelihoods for different members of the community while helping to stabilize soils and regulate water flows. Co-benefits from livelihood creation and reduced damages from disasters are crucial for community and government buy-in and integration of NbS in future planning processes.

Resources

Building block 3: Project Learning Activities

CityAdapt’s various implementation activities are carried out with demonstration sites to showcase benefits to surrounding populations and inspire replication. This includes demonstration sites for edible mushroom cultivation, urban gardens, roof rainwater harvesting systems, beekeeping, water infiltration systems, agroforestry, and other activities.

CityAdapt also emphasizes learning from project activities, especially for planning officials and communities to take ownership and help them continue after project end. It has therefore produced or is producing an array of knowledge products, including manuals, policy briefs, case studies, technical guidelines, and education material for children. A key aspect of this work has been highlighting NbS’ cost-effectiveness in comparison to conventional solutions (see story maps).

One key is a virtual class with 45 students that work on adaptation-related issues in their respective 17 countries. All the students reported an across-the-board improvement in their knowledge of NbS for urban adaptation. This class model will now be expanded to other regions. These learning components help to build the case for further NbS integration in urban planning and policy while spreading CityAdapt’s lessons to other actors interested in using NbS for their respective cities.

Enabling factors

Key factors for this building block’s success are the baseline established by the vulnerability assessment, and the ongoing participation in activities by local communities.

Lesson learned

Academic institutions with a local presence must be involved in the project, for example via master’s students’ thesis research. The academic institutions and their students need real-world projects for applied learning, and the adaptation activities need someone to carry on with monitoring and evaluation. This helps to ensure project sustainability and the continuity of project implementation and essential M&E tools. At the same time, local participation in monitoring (also referred to as citizen science in many contexts) is key for buy-in and ownership of activities, in addition to collecting useful data. School activities have been highly advantageous for generating local interest in project activities, as children take lessons learned home to share with their families. The pandemic has represented a major challenge to this effort, but the project has adapted, and created virtual educational games for children to play at home with their parents and teachers.

Resources

Impacts

Environmental: To date, CityAdapt has restored some twenty kilometers of riparian areas and more than 300 hectares of forest and coffee plantations (agroforestry), including the digging of infiltration ditches to absorb water and reduce flood risk while ensuring reliable supplies throughout the year. This work reduces the risk of dangerous flooding and subsequent landslides.

Social: Women are included fully in project design and implementation, including alternative livelihood projects such as beekeeping and mushroom cultivation. This inclusion has helped create a space for discussion on gender issues and greater sense of self-advocacy. Additionally, CityAdapt’s vulnerability assessments use a gender-differentiated approach to capture how climate change affects men and women differently, ensuring the project activities target more marginalized parts of society with greater need, which often tends to be women heads of households.

Economic: Community rainwater harvesting systems have helped build social cohesion for managing hydrological resources together. Access to that water saves communities time and money that would otherwise be spent collecting water far away or paying for its delivery. Alternative livelihoods (mushroom cultivation, beekeeping) are generating additional sources of income, including an extra $152 USD per month for Xalapan households.

Beneficiaries

194,090 people (50% women) across the three cities and countries

190 decision-makers and planning officials (50% female)

Women’s producer groups, coffee farmers, community youth groups from local schools, etc.

Sustainable Development Goals

Story

Sponge City

In 2020, Tropical Storm Amanda descended on El Salvador’s capital, San Salvador, causing more than 150 landslides and 20 floods and tearing apart roads, power lines, and some 30,000 homes.

Farmer Hector Velasquez, whose land sits on the slopes of San Salvador Volcano, was in the storm’s path, which dumped two metres of rain on his farm, sparking a landslide that wiped out 3,000 m2, or an area about half the size of a football field.

“The landslides take away all the crops planted in that area, so you need to reinvest,” says Velasquez, 42, a father of two. “It drains resources when resources are scarce, to begin with.”

When Velasquez was a child, rainfall in San Salvador was mostly a continuous-but-light drizzle spread across eight months. The soil had time to absorb the water. But, in recent years, climate change has made extreme storms more common in El Salvador. They are especially devastating around the capital, where pavement prevents rainfall from being absorbed.

In San Salvador, floods and landslides wash away valuable topsoil, and with it the fertility of the coffee plantations. “The soil, for us farmers, is the wealth of our farm,” says Velasquez. “If we don’t have it, we don’t produce.”

But a movement is underway to change that. City officials and coffee farmers like Velasquez, with support from UNEP, have launched CityAdapt to restore 1,150 hectares of forests and coffee plantations to revive San Salvador’s ability to absorb rainfall and produce coffee.

When vegetation is replaced with concrete, the ground loses its permeability. But trees and other vegetation can be used as sponges, drawing enormous quantities of water into the earth, preventing erosion, limiting floods and recharging groundwater for times of drought.

CityAdapt is also restoring hundreds of hectares of coffee farms like Velasquez’s destroyed by Amanda by installing infiltration ditches, imitating the drainage that streams and rivers used to provide naturally. It is building more than 62km of infiltration ditches in San Salvador and 3,514 fruit trees have been planted during reforestation to provide extra resources to local communities.

Back on Hector Velasquez’s coffee farm, when asked what he would say to someone that doesn’t believe in climate change, he laughs: “We have a saying: There isn’t a person more blind than the one who doesn’t want to see. And there isn’t a person as deaf as the one who doesn’t want to hear.”