Coastal Capital: Economic Valuation of Belize’s Reefs and Mangroves

“Coastal Capital: Belize” addresses threats to Belize’s coastal ecosystems such as unchecked coastal and tourism development and overfishing – by assessing the contribution of reef- and mangrove-associated tourism, fisheries, and shoreline protection services to Belize’s economy. Our results were used to justify new fishing regulations, a successful damage claim against a ship that ran aground on the Belize Barrier Reef, and a ban on offshore oil drilling.

Context

Challenges addressed

Location

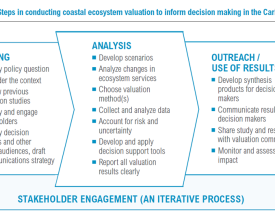

Process

Summary of the process

Building Blocks

Partnership and meaningful stakeholder engagement

Enabling factors

Lesson learned

Collection of environmental/socioeconomic information

Enabling factors

Lesson learned

Valuation of coral reefs and mangroves

Enabling factors

Lesson learned

Training in economic valuation

Enabling factors

Lesson learned

Targeted communication products and outreach

Enabling factors

Lesson learned

Impacts

Influenced by Coastal Capital: Belize, the government of Belize has taken significant steps to protect its coral reefs and mangroves. After the container ship Westerhaven ran aground on the Belize Barrier Reef in 2009, the government decided to sue for damages – something that had not occurred with past groundings. In a landmark decision – which mentions Coastal Capital and the importance of reefs to Belize’s economy – the Supreme Court ruled in 2010 that the ship’s owners must pay the government ~US$6 million in damages (reduced to ~US$2 million in 2011). The government also tightened a number of fishing regulations, including banning the harvest of parrotfish and banning spearfishing within MPAs. Belizean NGOs also used the valuation results to successfully advocate a ban on offshore oil drilling, and continue to use the results to further their advocacy. The valuation has also had impacts beyond Belize; for example, a coastal manager in St. Maarten replicated the study and convinced his government to establish an MPA in 2010, and the Jamaican government was awarded damages for a ship grounding in 2011, citing the Belize case as precedent.