Community Marine Conservation. The start of the Locally Managed Marine Area movement in Kenya in response to the decline of fish in Kuruwitu, on the North Kenya coast.

Kuruwitu Conservation and Welfare Association(KCWA) was set up in 2003 by members of the community concerned about the degradation of their seas. Over-fishing and effects of climate change needed to be addressed before the marine ecosystem was damaged beyond repair. Fishers and concerned residents who remembered how healthy and productive the sea had been in the past felt it necessary to act before it was too late. In 2005 they took the unprecedented step of setting aside a 30-hectare Marine Protected Area (MPA). This was the first coral based Locally Managed Marine Area (LMMA) in Kenya. Twelve years on, the area has made a remarkable recovery. With fishing prohibited within the MPA, fish have grown in abundance, size and diversity. Fish catches in the area have improved,and alternative income generating enterprises have been introduced. Kuruwitu has become a model for sustainable marine conservation. The KCWA share their knowledge with other local and regional coastal communities.

Context

Challenges addressed

Kuruwitu is mostly a subsistence-based fishing community and relies on the local marine resource for its livelihood. The increase in population meant more fishers in the area leading to overfishing. Desperation meant smaller fish were being caught often using unsustainable fishing techniques. Smaller catches led to a reduction in income to an already impoverished community who had no other skills other than fishing. The fishing grounds became unsustainable, and fishers were no longer able to feed their families leading to increased crime. One of the significant challenges was getting the majority of fishers to come together and understand that the closure would benefit them in the long term. Working towards a solution of sustainable fisheries the situation of illegal nets needed to be addressed. Funding was required to replace the nets and to initiate alternative enterprises. This was difficult with a new, unproven project. Poaching from the minority also needed to be addressed.

Location

Process

Summary of the process

Although the set-up of an MPA is complicated and relies on many interactive factors, three main ingredients need to be present throughout - legal framework, management and community buy-in and benefit. They are all connected and need to work separately and in unison. An institutional framework with legal requirements and management procedures is necessary to create a solid foundation. For conservation to work in areas where poverty is present, there has to be a welfare component.

Building Blocks

Marine protected area (MPA)

Community recognition that action was needed to improve dwindling fish stocks was followed by the identification of various stakeholders to help us achieve our goals. Communication, outreach and awareness building programmes were set up and a visit to a similar project in Tanzania went ahead in 2004, and encouraged the community to use local marine resources sustainably.

A democratic decision to close an agreed lagoon area was agreed. Legal and policy frameworks were put in place, and the first LMMA in Kenya was approved in 2006 under the National Environmental Management Authority. Following this, a collaborative governance model has emerged under Beach Management Units (BMU's), where fishers and government work together towards sustainable fishing and improved livelihoods. In setting up the MPA, we went through various phases; conceptualisation; inception; implementation; monitoring; management and ongoing adaptive management.

Enabling factors

The realisation by the community that there was a significant crisis looming and a determination to act for the sake of future generations was a crucial factor in the implementation process. Trust and belief in a positive outcome was paramount. Initial funding for alternative enterprises and support from key partners was necessary for technical and advisory capacities. An area was chosen that had good recovery potential with help from a scientist that had previously been monitoring that part of the coast coupled with local knowledge.

Lesson learned

From the outset a clear strategy and management plan devised with maximum participation from community members is critical. Listening to the elders within the community creates an essential link between past and present. Targets and goals need to be achievable and clear timelines need to be set and adhered to keep the support of the community. The entire community needs to benefit from the project, and livelihoods need to improve tangibly in order to maintain support and create a sense of ownership that gives the project longevity. A community welfare aspect should be part of the strategy. Awareness, education and sharing of information need to be maintained, and a willingness to an adaptive management approach is vital. Learning from mistakes, sharing knowledge and creating close alliances with other similar organisations helps the project progress quickly. Creating collaborative partnerships and following clear procedures and legislative guidelines strengthen the structure of any entity. Good governance from the outset with a clear constitution that is followed at all times.

Institutional framework, legal requirements and management

Since KCWA initiated the first MPA in Kenya, the policy that regulates the recognition of a Locally Managed Marine Area was not clear. KCWA engaged other stakeholders like the East African Wildlife Society who helped with legal frameworks and policy advocacy. The recognition of this area under the National Environmental Management Authority (NEMA) secured fishers rights to manage their area and paved the way for the 20 other community projects that have sprung up following the KCWA movement.

This new legislation recognised the fisher’s effort for a collaborative governance model for the management of the marine territory. A 5-year adaptive management plan was drawn up drawing from local knowledge of the area with the help of other strategic partners. Rules and governance of the project were set out in a constitution document.

Enabling factors

Original strategic partnerships, both legal and technical in this pilot project required a clear concept of what we wanted to achieve and was vital to get past the implementation stage. Recognition by the relevant Government bodies that the concept of communities managing their resources was the next step in marine conservation created an open, collaborative way forward.

Lesson learned

When starting a pilot project choosing the right partners is essential. This provided a challenge in some cases. The agendas of the partners sometimes differed from our vision and often needed to be reviewed and changed. Legalising and managing a new concept often through unchartered territory was time-consuming and required patience. Creating a robust legal foundation along the way was essential to successes in the future.

Community welfare

Although the MPA quickly recovered and livelihoods began to improve part of the management plan was to introduce other non-fishing based enterprises in an attempt to achieve a self-sustainable solution. Initially, outside funding had to be sourced to enable this to happen, and various grants were forthcoming. Initially, a tourism business taking advantage of the improvement of coral and biodiversity within the MPA attracted visitors. This produced training opportunities, created steady employment to fishers improving their livelihood and taking pressure off the marine resource. The youth were trained in furniture making from old dhows, honey was produced, sustainably caught fish sold to restaurants, vegetables and crops grown and sold, various aquaculture projects are underway, and the women group have various enterprises including tailoring and a craft shop selling products made from driftwood and natural soaps. A loan scheme allows the members to finance other projects. A portion of the profit goes towards community welfare needs like water, health and sanitation. Beach waste is collected and sold to recycling companies. A school education programme educates the children on the importance of sustainable use of resources, and we provide trips within the MPA.

Enabling factors

The MPA is the heart of our project. The protected breeding ground means improves fishing in the area with a knock-on effect of improved livelihoods. The MPA has become an attraction and visitors bring in much needed funds which go towards employment, training, the running of the organisation and setting up other businesses. While we faced challenges and objection to setting aside the area of the MPA, the results have shown it was worth it.

Lesson learned

For conservation to work it needs to be accompanied by tangible alternative opportunities and real improvements in livelihoods. The resource that is being conserved needs to be valuable and important to the local community. All the components have to work in unison and benefit the community. Whilst an LMMA takes time, understanding and patience to set up and establish, it becomes an efficient and productive hub from which other projects can grow. It has multifaceted benefits that can cover both conservation and community welfare. We learned along the way that there is no short cut to community buy-in. In our case, we were working with a subsistence community and even short-term threats to their livelihood meant direct hardship that led to resistance. We learnt that most of the resistance we met was underpinned by a real fear of economic insecurity. Once we understood that the needs of the community were paramount, we could devise relevant and impactful strategies to achieve our conservation goals.

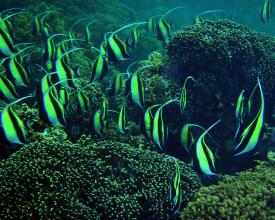

Importance of conservation

Scientists, who have been monitoring the area before it was closed, estimate a 500% increase in biomass within the area since the closure. The area, previously covered with sea urchins, is now a thriving biodiversity hotspot with the balance restored. The elders report new species in the MPA that have not been seen in living memory. The coral, previously destroyed by human feet, has recovered quickly and the lagoon area is now known as one of the best snorkelling destinations on the Kenyan coast. Local and international students come and learn in our living marine classroom. Turtles feed on the seagrass beds undisturbed, and the number of nests has increased significantly. The area has returned from being a marine desert to a marine paradise and a critical model globally that shows how a poor community can help conserve nature and benefit from it too. Bigger and better catches outside the MPA has ensured support for the permanent closure.

Enabling factors

The MPA could not have gone a head without the belief and forsight of the fisherfolk in the area and the acceptance to beleive that positive change was possible even in difficult circumstances. Local knowledge from the elders ensured a suitable site for the closure was chosen. Scientific research also supported the choice as having the most potential for long term improvement. Regular updates on improvements within the MPA has helped sure up the belief that it is successful as a breeding area.

Lesson learned

That nature is resilient and can recover amazingly quickly if left alone to do so. Identifying needs and fostering willingness to embrace change can improve livelihoods. The importance of undertaking an environmental impact assessment on the area, underpinned by research and local knowledge, before the project started has been a critical factor towards the success of the MPA. Constant awareness and updates of the improvement in the MPA need to be communicated back to the community. Analysing the information can be used to put into perspective in the socio-economic impact. The importance of communication of our progress back to the community has been something we have had to improve. When the community understands and sees the benefits from change they are, understandably, more willing to accept it.

Impacts

The development of sustainable non-fishing based initiatives has shifted dependence on subsistence fishing taking pressure off the fishing grounds. Fish stocks have improved dramatically within the LMMA, and an independent report shows a considerable increase in fish biomass and biodiversity of all marine life in the area. This has increased fish catches in the neighbouring fishing grounds improving livelihoods. Turtles and nests in the area are protected through a community compensation scheme. Communities from along the coast and from other neighbouring countries visit Kuruwitu to see our living classroom. At least 20 other similar projects have started by other coastal communities inspired by KCWA. KCWA demonstrated the importance of community involvement in natural resource management plans; a principle that has influenced a change of policy away from the state to the local communities. Kuruwitu has been chosen to pilot a co-management initiative working with various stakeholders covering an area of approximately 100 square kilometres. This is one of the first collaborative management schemes of its kind on the Kenyan coast and will set a precedent in the future.

Beneficiaries

Improved catches benefitted the fishing community and livelihoods improved. KCWA engaged youth in non-marine based income activities and training. A women's group was set up, and a marine-based education programme was established for local children.

Sustainable Development Goals

Story

Up and down the Kenyan Coast there is a remarkable upsurge in communities beginning to think differently about the marine resources they depend on. A new generation of fishers is looking for ways to responsibly manage their resources to ensure not only their own future but beyond. For generations, fisherfolk all along the Kenyan coast have been able to both put food on the table and make a subsistence living from fishing. However, there came a point where the size of fish and the numbers caught began to reduce to a point where they could no longer live this way. In a very short period, fisherfolk were facing the collapse of the only livelihood they knew. This slow-burn crisis focused attention on a closer look at the issues affecting what was, and in most cases, what wasn't being landed in their nets. ‘We never questioned how we lived. Our fathers and grandfathers were fishermen, and in our village, it was the only path we knew. When our nets began to fail, we were faced with an unknown future.' Dickson Juma, Fisherman. The main factor identified was the overpopulation in the area which led to overfishing. A community body, the Kuruwitu Conservation and Welfare Association (KCWA) was set up to ensure the community had a say in the management of the resources they depended on. With the help of strategic partners, institutional frameworks and legal structures were set up. After an in-depth consultation, in 2006 the Association voted to close off part of the lagoon area a marine protected area. The rejuvenation of fish stocks in the area was visible quickly, and the fishermen’s catches in the surrounding area began to increase. Funding support helped KCWA set up corresponding alternative income generating enterprises training fishers and their families in other vocations and creating employment taking pressure off the fragile marine environment. Fifteen years on and the trickle of visitors is a modest but steady stream who are happy to pay to snorkel within the healthy and vibrant marine protected area. In 2017, the KCWA was the proud winner of the UNDP's Equator Prize is awarded to recognise outstanding community efforts to reduce poverty through the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity. Recognition for the hard work and sacrifice of the community for a larger, common goal, has been an important milestone in the project's development.