Community participation in PA management provides development benefits

The Parc Marin Mohéli, Comoros, was established in 2001 through a negotiated process agreed by the ten main village centers around the area. However, during political instability, external support dried up in 2005, and pressures on coastal ecosystem resources vital to the local economy have increased. The solution has been to revive the village dynamics around the protection of the park, and since 2014 to develop income generating activities for both local communities and the park’s management.

Context

Challenges addressed

Location

Process

Summary of the process

Building Blocks

Revitalizing community engagement in park management

Enabling factors

Lesson learned

Community action for sustainable artisanal fisheries

Enabling factors

Lesson learned

Sustainable agriculture in watersheds and vulnerable coasts

Enabling factors

Lesson learned

Impacts

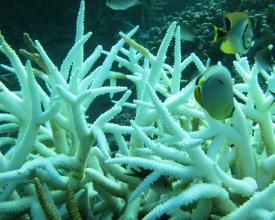

- Re-addressing the institutional and governance framework for the Mohéli Marine Park has resulted in a more productive arrangement between local villages and protection authorities. Dialogue concerning impacts on local resources and livelihoods has moved from one of costs and claims to one of action and benefits. - Trade-offs between protection and exploitation have become possible, and resulted in reduced impacts on marine and coastal ecosystems. New areas of ‘no-take’ zones have both increased ‘spill-over’ and recovery of key commercial species (octopus, holothurians) and provided strict biodiversity havens within the Mohéli island ecosystem. - The active participation of villages in reducing watershed and coastal erosion are perceived as beneficial for their community, not just for the protected area.