Decision-making toolbox for inclusive conservation in the Sierra de Guadarrama National Park

The Sierra de Guadarrama National Park covers 33,960 ha through the Central Mountain System of the Iberian Peninsula in the Madrid and the Castilla y León regions. The National Park includes glacial cirques, unique granite rock formations, alpine lakes, grasslands, and pine forests that contain rich biodiversity. The National Park has almost 2.5 million visitors per year and is used for sports and recreation activities. It also encompasses a variety of local stakeholders engaged in diverse activities such as extensive livestock, forestry, biodiversity conservation, education and research. This solution introduces a set of tools to help protected areas managers and practitioners enhance social engagement in conservation decision-making by identifying, navigating and balancing visions, tensions, and power relations between stakeholders. The toolbox has been created in the context of the ENVISION project to support the creation of socially inclusive policies and management actions in protected areas.

Context

Challenges addressed

The National Park’s authorities, in their endeavor to balancing conservation goals with human well-being, need to deal with a variety of perspectives, knowledge, and values from a wide range of actors. There are state administrations with intersecting governing competences in the area and stakeholders engage in diverse and often competing activities such as outdoor sports, extensive livestock farming, forestry, conservation, education and research. In turn, many visitors are attracted by the National Park proximity (less than 100km) to Madrid's large metropolitan area (over 6.5 M inhabitants) and the mid-sized city of Segovia (around 50,000 inhabitants). These multiple and competing uses create social tensions around how the park should be governed. This scenario raises the challenge of how different visions, values, knowledge and power relations between stakeholders can be considered for conservation governance and balanced for achieving positive conservation and well-being outcomes.

Location

Process

Summary of the process

The building blocks include a diversity of decision-making tools that can be combined for addressing different dimensions related to inclusive conservation. This set of tools aims to: 1) gather local knowledge and values (Building block 1), 2) elucidate visions and future scenarios for park management (Building block 2), 3) address power dynamics and promoting engagement in collective action (Building block 3), and 4) strengthen the science-policy interface for socially inclusive governance (Building block 4). These tools can be used in an individual and complementary basis to support the creation of socially inclusive policies and management actions in protected areas worldwide. This set of tools can also be complemented and combined with other approaches and techniques that have been applied in other case study areas of the ENVISION project (https://inclusive-conservation.org/). More information about these tools can be found in the PANORAMA solutions for Utrechtse & Krommerijn (The Netherlands), Västra Harg (Sweden), and Denali National Park and Preserve (United States).

Building Blocks

Gathering local knowledge and values

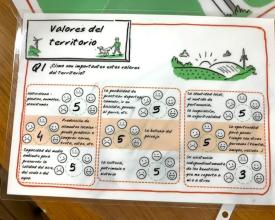

To facilitate place-based processes that foster inclusive conservation it is necessary to collect local/traditional knowledge, views, and values from multiple stakeholders. Some methods to gather such information were used in the Sierra de Guadarrama National Park:

- Oral histories and historical datasets review to reconstruct how past visions and drivers of environmental impact have changed over the last 50 years and inform current and future conservation goals;

- Interviews with local stakeholders on 1) how participation works in the protected area and potential barriers/opportunities for more social engagement, and 2) their visions for park management, the values and knowledge that underpin the visions, and their perceptions of landscape changes and the underlying drivers;

- Face-to-face surveys with residents, including participatory mapping tools (i.e. Maptionnaire) about landscape values and ecological knowledge. Online surveys with local stakeholders to identify changes in their visions, values and perceptions of the landscape after the COVID-19 pandemic; and

- Deliberative processes embedded in a participatory scenario planning exercise that used cognitive and emotional maps to collect collective knowledge of the protected area while capturing intertwined affective relationships.

Enabling factors

- Created an atmosphere of shared understanding, respect and trust with participants to facilitate collaboration along the process;

- Clarified the project's goals and practical outcomes to manage expectations and stimulate participation; and

- Co-designed with participants an outreach plan to better disseminate the generated outcomes while making participants realise about the impact of their engagement and fostering learning from others' experience.

Lesson learned

- Planning activities with stakeholders carefully to avoid overwhelming them with requests;

- Developing activities according to the timetable, schedule and disruptive events situations (e.g., the COVID-19 pandemic) that work better for most participants;

- Using quantitative research approaches to gather context-based knowledge may result in biased information. A mixed-method approach based on quantitative and qualitative data can help avoid bias and get a more in-depth knowledge of the context;

- Online methods work well and their implementation saves time and money when compared with face-to-face events, but are less effective in achieving good personal interactions;

- Synthesizing and sharing the knowledge is appreciated by the stakeholders. For example, the knowledge gathered from individual stakeholders about landscape changes in the National Park was shared with the stakeholder group at a workshop with the opportunity for short discussions. Stakeholders indicated that they had learned and understood other peoples’ points of views on landscape changes and drivers of change.

Elucidating visions and future scenarios for park management

These three tools help to identify visions and elaborate future scenarios, in a participatory way, for protected areas management:

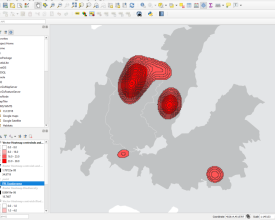

- Participatory mapping (PGIS), a tool to visualize information in a particular geographical context focusing on a certain issue of interest. This tool was used in surveys to elicit the residents’ visions based on perceptions of landscape values and local knowledge;

- Streamline, an open-source narrative synthesis tool that integrates graphics in the form of canvases and tiles, facilitating interviews and discussion groups in a creative and stimulating way. Streamline was used with stakeholders’ expressing their values and preferences for management actions, and sharing their knowledge of changes in the landscape;

- Participatory scenario planning exercise, a deliberative process that was facilitated about plausible and desired futures through a two-day online workshop (due to the Covid-19 pandemic) with stakeholders. Based on the current socio-ecological conditions and the factors driving change, participants weighed up what could happen in the coming 20 years, discussed implications for biodiversity conservation and the quality of life of those who currently enjoy the ecosystem services it provides, whilst identifying the strategies to address them.

Enabling factors

- Inviting and giving voice to stakeholder groups that are often poorly included in social spaces to publicly debate about conservation;

- Creating a collaborative process built upon dissent-based approaches to promote a transparent and horizontal work-space;

- Building workgroups with a balanced representation between stakeholder groups, regions of the residence and gender, helps so that not only majoritarian voices are heard.

Lesson learned

- Local facilitators and collaborators were essential to approach a big sample of local residents in the surveys and the workshop;

- Online processes require significant efforts and human resources to handle multiple platforms and technical issues simultaneously. Specific expert facilitation skills are required;

- Scenario planning methodologies should more strongly consider different potential disturbances and how drivers of change in the near and far future can be affected by wildcard events such as a pandemic.

Addressing power dynamics and promoting engagement in collective action

These three decision-making tools were crucial to address power dynamics and promote stakeholders' participation and engagement in collective action in the National Park:

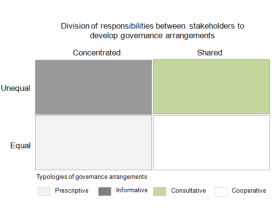

- An analytical tool to characterize types of governance arrangements in the protected area. Formal and informal governance arrangements were classified in terms of stakeholders’ responsibility (shared vs. concentrated) and influence (equal vs. unequal) into four types: prescriptive, informative, consultative, and cooperative. By applying this tool in the National Park we identified challenges for more socially inclusive conservation while enhancing existing participatory mechanisms and delineating new ones;

- Theatre-based facilitation techniques to address power dynamics between stakeholders. By using them in a virtual workshop, participants deliberated on their roles and power relations around conservation governance and how these may be reconciled to improve collaboration;

- A context-specific boundary object to facilitate collective action for conservation governance. Using this graphical tool in a workshop, participants assessed their level of willingness to put several strategies into practice. The tool visualized the results graphically as a proxy of the potential willingness to move from theory to practice.

Enabling factors

- The analytical tool to characterize governance arrangements requires data collection about the existing decision-making mechanisms behind each arrangement identified, the stakeholders engaged and how they are engaged;

- The art-based approaches and context-specific boundary object require a process based on co-learning and knowledge co-production approaches through which stakeholders deliberate on power dynamics, conservation challenges and define collaborative strategies to address them.

Lesson learned

- Analyzing both formal and informal-based governance arrangements serves as a means to understand how participation in conservation decision-making is actually shaped within protected areas governance and how to improve stakeholder engagement given the context;

- It is important to consider informal governance mechanisms to understand potential trade-offs because they can lead to both positive and negative outcomes for conservation;

- Stakeholders’ responsibility and influence are key analytical axes to delineate participatory mechanisms in order to identify opportunities for more socially inclusive conservation;

- Art-based methods are useful to incorporate power relations aspects into conservation debates;

- Elucidating unequal relations for conservation governance offers opportunities to clarify stakeholders’ roles and their responsibilities and facilitate a better understanding of how these may be reconciled to improve collaboration;

- The assessment of stakeholders’ willingness to be involved in putting the strategies into practice is a crucial factor to guide collective action.

Strengthening the science-policy interface for socially inclusive governance

The elaboration of a plan for creating understanding and collaboration between researchers and decision-makers was a necessary tool to promote that scientific knowledge can have impacts on the policy domain. This plan entailed the following actions:

- Face-to-face or online meetings to formally introduce the research project to the protected area decision-makers and managers while using media (e.g., radio and press), and developing seminars to inform local residents and other stakeholders about the project;

- Invitation to decision-makers and managers to be involved in the project activities (e.g. local knowledge alliance, film and meetings);

- Tailoring the research activities to the decision-makers agenda to facilitate their participation;

- Organization of regular meetings, webinars and newsletters in local languages to inform about the project advances and findings;

- Development of workshops with decision-makers to analyze the applicability and usability of resulting tools and other research outcomes within the protected area;

- Dissemination of research reports in local language before academic article publications to validate the results;

- Writing posts in the national park’s blog and other related websites to disseminate research findings within the protected area channels.

Enabling factors

- Conducted key-informant interviews with staff from the Sierra de Guadarrama National Park to identify the interests and needs of decision-makers and align our research activities;

- Involved key staff from the National Park with the capacity to promote institutional changes and decisions to facilitate that our scientific insights might reach impacts on the management setting;

- Organized a workshop with decision-makers to evaluate research tools in terms of applicability in the management cycle in order to facilitate their use by them.

Lesson learned

- An early exploration of the management and decision-making setting is relevant to plan for and develop solution-oriented research that can be implemented within the management cycle;

- Periodical meetings between researchers and decision-makers help scientists gain awareness of the variety of directions in which their research can impact the policy domain, and decision-makers gain access to the best available evidence to make decisions. This is crucial to align research to the decision-makers' needs and facilitate the use of science in the management setting;

- Producing scientific outcomes that are translatable into real outcomes in the management can motivate decision-makers to participate in the research;

- Writing policy reports to introduce scientific insights into the native language facilitates the use of scientific information by decision-makers;

- Planning the research activities so that overwhelming decision-makers with multiple requests is avoided.

Impacts

Part of the research findings related to participation has served as practical guidance to understand participatory mechanisms and support some strategies/actions included in the participation and volunteering subprogram of the Sierra de Guadarrama National Park developed by the protected area managers and decision-makers. Specifically, the set of decision-making tools detailed in the building blocks (1 - 4) were considered of interest by them based on their potential applicability within the protected area. As the subprogram has just been initiated, we do not yet have an understanding whether all of these tools will be utilized.

In addition, over 100 people have been actively engaged in our research activities. Through such activities, they have reflected and learned about different stakeholders' visions, preferences, tensions, responsibilities and power relations to move towards better social engagement in conservation decision-making.

Beneficiaries

Protected areas’ managers and practitioners can directly benefit from the toolbox to practice socially inclusive conservation. Stakeholders and local communities may also benefit since these tools can facilitate their participation in decision-making.

Sustainable Development Goals

Story

Judit Maroto studied Forest Engineering and a Master of Science in ecosystem restoration. She has dedicated herself to environmental conservation throughout both research and management activities. She currently works at the Sierra de Guadarrama National Park management unit in the region of Castilla and León (Spain). As a staff member of the National Park, she is responsible for the day-to-day management of this protected area. Among her functions, she is in charge of the participation and volunteering subprogram of the National Park. From the beginning of the ENVISION project, she has been involved in our research activities as a member of our local knowledge alliance, has taken part in regular meetings with us, and has participated in diverse dissemination activities related to the ENVISION project (e.g. video and webinars). In addition, she has participated in: 1) semi-structured interview aimed to get a better understanding of formal and informal participatory mechanisms implemented in the National Park; 2) participatory scenario planning exercise with local stakeholders to deliberate collectively about plausible and desired futures/visions for the National Park; and, 3) workshop with decision-makers and experts on protected areas management to analyze the main challenges and opportunities of the current participatory setting within the protected area, define management strategies for facilitating social engagement in management, and assess research tools that might be useful to support more socially inclusive conservation approaches. Feedback from her and other experts on protected areas management has facilitated that our research might better respond to some of the management needs and challenges of the National Park. This facilitates research applicability into the management cycle to craft participatory mechanisms and management actions in an inclusive manner. In May 2021, she confirmed the usability of our findings to reinforce the development of the participation and volunteering subprogram of the Sierra de Guadarrama National Park, so these are being considered to support such subprogram. We hope that our recent science-policy collaboration can continue in the future so that research can support the creation of socially inclusive models of governance in the Sierra de Guadarrama National Park and other protected areas.