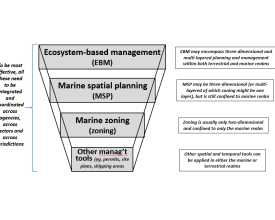

Effective zoning as a key spatial planning/management tool

Context

Challenges addressed

Location

Process

Summary of the process

Building Blocks

Multiple-use zoning

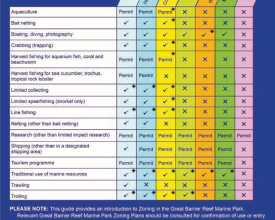

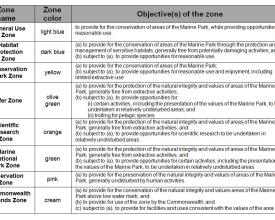

In some parts of the world, zoning is based solely around allowing, or prohibiting, specific activities in specific areas. In the GBR a spectrum of zones exists, each with differing zone objectives; these zones allow a range of activities to occur provided each activity complies with the relevant zone objective. The provisions of the Zoning Plan apply to all users in the GBR. The Zoning Plan sets out in detail two specific lists of ‘use or entry’ provisions for each zone; these help determine the types of activities that are appropriate in that particular zone. 1. The first list indicates activities that are allowed to occur in that zone (‘as of right’) and which do not require a permit; 2. The second list stipulates which activities may occur in that particular zone but only after a permit has been assessed and, if the application meets all the necessary requirements, a permit has been granted. The regulations specify the assessment process and criteria for a permit; these vary depending on the proposed activity. Some zones may also stipulate restrictions on types of fishing gear which also provides differing levels of protection. If an activity is not listed in either (1) or (2) above, it is prohibited in that zone.

Enabling factors

The 1975 legislation specified that a plan depicting spatially derived zones (i.e. zoning) was to be a key management tool for the GBR Marine Park, and zoning plans were required by the legislation to define the purposes for which certain areas may be used or entered. The objectives of zoning have ‘evolved’ since the 1975 version of the Act (refer Day 2015) recognizing a need today to protect the full range of the biodiversity of the GBR rather than just keystone species or habitats.

Lesson learned

- To assist public understanding, the allowable activities in the Zoning Plan have been summarized into a simple activity/zoning matrix (see Photos below). However, the statutory Zoning Plan (i.e. subordinate legislation under the Act) must be the legal basis for determining which activities are appropriate in a zone.

- Zoning maps are a publicly-available form of the statutory Zoning Plan; however, to legally determine exactly where a zone boundary occurs, the actual zone descriptions detailed in the back of the statutory Zoning Plan must be used.

- Just because the Zoning Plan states an activity is able to occur with a permit, it does not automatically mean a permit will always be granted; the application still needs to be assessed and only if it meets all the necessary criteria, is a permit granted.

Zone assignment by objective rather than by activities

The difference between zoning by objective rather than zoning by activity is best explained by example; a ‘no-trawling’ zone may indicate clearly one activity is prohibited (i.e. all trawling is banned in that zone), but it may not be clear as to what other activities may be allowed or not allowed. The objective of the Habitat Protection Zone enables a range of activities that have (relatively) minimal impacts on the benthic habitat(s) to occur within that zone; for example, boating, diving, and limited impact research are allowed, as well as allowing some extractive activities like line fishing, netting, trolling and spear-fishing (i.e. some but not all, fishing activities). However the zone objective and related zoning provisions clearly prohibit bottom trawling, dredging or any other activity that is damaging to the sensitive habitats in that zone. In most oceans there are many existing or potential marine activities that need to be managed but many of these activities are complementary and can occur within the same zone; if zoning is used to address all existing activities (and ocean zoning is certainly one important tool to do so), then it is preferable that zoning be by objective rather than by each individual activity.

Enabling factors

The Zoning Plan is a statutory document that includes all the specific details of the zoning (e.g. Zone objectives (see Resources below), the detailed zone boundaries, etc.). The Act provides the ‘head of power’ to prepare a zoning plan and includes a section on the Interpretation of zoning plans (section 3A) and details about the objects of zoning, what a zoning plan must contain and how a zoning plan must be prepared (sections 32-37A).

Lesson learned

- If a zone objective has multiple parts, there must be a clear hierarchy within the objective. For example, if the objective is to provide for both conservation and reasonable use (as shown for most GBR zones - see Resources below), the second part is always subject to the first (i.e. reasonable use can only occur if it is subject to ensuring conservation).

- The GBR Zoning Plan also has a special ‘catch-all’ permit provision in (“any other purpose consistent with the objective of the zone…”). This provides for new technology or activities that were not known when the Zoning Plan was approved. It provides an important ‘safety net’ enabling an activity which is not in one of the two lists explained in BB1 to still be considered for a permit provided it is consistent with the zone objective.

Resources

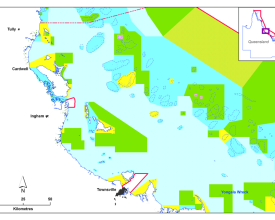

Coordinated-based zone boundaries

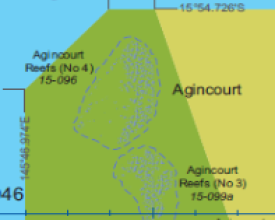

Zone boundaries may be described as a specified distance from the edge of a geographical feature (e.g. ‘500 m from the reef edge’). This normally results in an irregular shaped zone boundary. Depicting a reef or a group of reefs in this way may look ecologically appropriate on a map, but using the edge of such features to draw zone boundaries has proven very difficult to interpret on the water. For example, many reef parts are fragmented or at times submerged, so it is difficult on the water to determine the reef edge, and then use that to estimate a distance. Furthermore it is not easy to estimate 500 m (or even 100 m) on the water. Coordinate-based zone boundaries, based on longitude/latitude and shown in degrees and decimal minutes were therefore introduced in the 2003 GBR Zoning Plan. These fully encompass ecological features (i.e. well outside the edge of entire reefs/islands). Zone boundaries are orientated north, south, east and west for ease of navigation or comprise straight lines between two easily determined coordinates. Straight lines look less ‘ecologically appropriate’, but they are easier to locate and enforce in offshore areas, especially if using electronic devices e.g. global positioning system GPS or plotter.

Enabling factors

Building on the existing zoning, it is important that every zone has a unique number, referenced to a detailed description in the statutory Zoning Plan (see Resources) and with a unique zone identifier (e.g. MNP–11–031): a) MNP refers to the zone type (Marine National Park Zone) b) the first two numbers refer to its latitude (example shown above is at latitude 11°) c) The last number (031) enables a specific zone to be identified on the zoning maps and cross-referenced to the Zoning Plan.

Lesson learned

- Not every zone coordinate is shown on the freely available zoning maps; however the most important zone coordinates for most users are shown (e.g. no-fishing zones and no-access zones).

- Recognizing that not everyone has a GPS, inshore zone boundaries, however, are aligned with recognizable coastal features or identifiable landmarks or boundary markers (e.g. ‘the zone extends north from the eastern extent of the headland at xxx’).

- Signs showing the nearby zones are put at boat ramps along the coast (see Photos below).

- All zoning coordinates are provided to commercial suppliers of electronic navigation aids, enabling zones to be loaded into a GPS.

- In addition, all zone coordinates are freely available on the web or available as a CD to enable any user to plot the coordinates on their own navigation chart, or to locate a zone using their own GPS.

- All coordinates must be referenced to a specified official Geocentric Datum for accuracy (e.g. GDA94 in Australia).

Biophysical, socio-economic & management planning principles

The new network of no-take zones (NTZ) in the GBR was guided by 11 Biophysical Operational Principles developed using general principles of reserve design and the best available knowledge of the GBR ecosystem (see Resources). They included:

- Have a few larger (rather than many smaller) NTZs

- Have sufficient replication of NTZs to insure against negative impacts

- Where a reef is within a NTZ, the whole reef should be included

- Represent at least 20% of each bioregion in NTZs

- Represent cross-shelf and latitudinal diversity in the network of NTZs

- Maximise use of environmental information like connectivity to form viable networks

- Incorporate biophysically special/unique places

- Consider adjacent sea uses and land uses when choosing NTZs

Four Social, Economic, Cultural and Management Feasibility Operational Principles were also applied:

- Maximise complementarity of NTZs with human values, activities and opportunities;

- Ensure that final selection of NTZs recognises social costs and benefits;

- Maximise placement of NTZs in locations which complement and include present and future management and tenure arrangements; and

- Maximise public understanding and acceptance of NTZs, and facilitate enforcement of NTZs.

Enabling factors

An independent Scientific Steering Committee, including scientists with expertise in the GBR, helped to develop these principles, basing them upon expert knowledge of the ecosystem, available literature and their advice as to what would best protect the biodiversity. Careful consideration of the views of Traditional Owners, users, stakeholders and decision-makers was an essential pre-requisite before deciding the final spatial configuration of NTZs that could fulfil these principles.

Lesson learned

- Having a publicly-available set of planning principles assists everyone to understand how the NTZ network is developed.

- The principles are based on the best available science and expert knowledge but can be improved.

- A principle should not be considered in isolation; they all need to be treated collectively as ‘a package’ to underpin the number, size and location of NTZs.

- None of these recommendations is for ‘ideal’ or ‘desired’ amounts and they refer to recommended minimum protection levels. Protecting at least these amounts in each bioregion, and each habitat, helps achieve the objective of protecting the range of biodiversity.

- The “minimum of 20% per bioregion” principle is often misunderstood – it is NOT saying that 20% of every bioregion in NTZs must be protected; rather it recommends no less than 20% should be protected. In some instances that is only the minimum amount and in some less contested bioregions, a higher percentage protected is more appropriate.

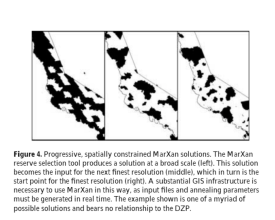

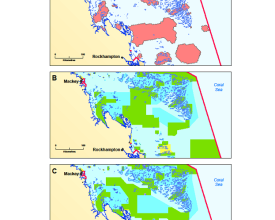

Use and limitations of decision support systems/tools

Decision-support systems (DSS) or analytical tools, such as Marxan or SeaSketch, are often promoted as a pre-requisite for effective marine spatial planning, providing a quick and reliable solution to a planning problem. It is natural for DSS users to hope that using the DSS will generate ‘the answer’ and hence provide the solution to their planning problem. More often than not, DSS produce simplistic results which need to be modified using other planning methods. All DSS tools have limitations and cannot compensate for missing or incomplete data. They can produce unintended side-effects and often are unable to match the complexity of real-world planning problems. Planning outcomes are of little practical value if social, cultural and economic values are not considered – however rarely is such data readily available in a form amendable to a DSS or at the an appropriate spatial resolution. In the GBR, the DSS generated a ‘footprint’ of various ‘no-take’ zone options, but it could not cater for the eight zone types, so other planning methods needed to be applied. However the real benefit was the ability to generate metrics to inform the development of the best possible no-take zoning network.

Enabling factors

Marxan was developed by the University of Queensland as a modified version of SPEXAN to meet the needs of the GBRMPA during the Representative Areas Program and the development of the 2003 Zoning Plan. The images below show that Marxan did not produce the final zoning network in the GBR, but it did provide invaluable decision support through post-hoc accounting of various options, enabling a rapid assessment of the implications of each option in terms of each of the planning objectives.

Lesson learned

In reality a DSS cannot undertake the fine scale tuning and political trade-offs that inevitably occur in the final stages of planning, so it can never produce the final pragmatic solution for any planning task. Some shortfalls of DSS are:

- Some planning information, especially socio-economic data, may not easily be applied into a DSS.

- While a DSS may generate a ‘solution’, it is inevitably refined if/when socio-economic values are introduced. These values are often not represented in the data yet are often some of the most fundamental values for a socially-acceptable outcome.

- Poor data will always lead to a poor result.

- Most contemporary DSS tools are unlikely to meet all the needs of a user; in the GBR planning program even simple ‘rules’ such as ‘all reserves should be no smaller than ...’ were not able to be directly implemented by a DSS.

- Some stakeholders are wary of ‘black-box’ models or DSSs (e.g. Marxan or Seasketch) that they do not understand.

Working with the best available information/knowledge

When undertaking a planning or zoning task, rarely does a planner have access to all the information or knowledge that they would like for the entire planning area. Whether it might be more consistent ecological data across the entire planning area or a more complete understanding of the full range of social and economic information, a planner is often faced with the following choices:

- Waiting until they have more data (with the ultimate aim of accumulating ‘perfect’ information across all the required datasets); or

- Working with the best available scientific knowledge and accepting that while it is not perfect, it is adequate provided the deficiencies of the data are understood (by the planners and the decision-makers) and clearly explained to the public and to the decision-makers. Insufficient knowledge about marine ecosystems can impede the setting of meaningful objectives or desirable outcomes when planning. David Suzuki in 2002 questioned how can we effectively plan and manage when “… to date all we have actually identified are ... about 10–20% of all living things”, and “… we have such a poor inventory of the constituents and a virtually useless blueprint of how all the components interact?’’

Enabling factors

A good understanding of the wider context within which the MPA is situated is an important factor when planning. Due to the levels of ‘connectivity’ in the marine environment and the biological interdependency upon neighbouring communities, an MPA can only be as ‘healthy’ as the surrounding waters. Even a well-planned MPA will be difficult to manage if the surrounding waters are over-utilised, polluted or are themselves inadequately managed.

Lesson learned

- The reality is if you wait until you have ‘perfect’ information for planning, you will never start.

- Recognise that marine areas are dynamic and are always changing; and with technological advances, the levels and patterns of use are constantly changing, as are the social, economic and political contexts, so having perfect data is realistically an impossible aim.

- In virtually all planning situations, it is better to proceed with the best available information than to wait for ‘perfect’ data. However, if new data becomes available during the planning process, then incorporate it rather than ignore it.

- Those who are frequently on the water (like fishers and tourist operators) often know as much (if not more) about the local environment than the researchers – so draw upon their knowledge and use it to augment the best available scientific data.

- When resources are limited, seeking new data should focus on providing information that will be useful for ongoing management.