Food Sovereignty through Community Gardens in São Paulo/SP

The NGO Cities Without Hunger sets up community gardens on vacant urban land in the city of São Paulo's socioeconomically deprived East Zone (Zona Leste) to provide jobs, income, and to enhance food sovereignity.

Cities Without Hunger aims to enhance local residents' spatially and economically restricted access to high-quality fresh produce (high rates of unemployment, a low density of farmers' markets or supermarkets, low mobility).

The NGO provides agricultural training for people who have poor chances on the regular job market as community gardeners. Since 2004, the NGO has implemented 25 community gardens together with about 115 local residents who have started earning their livelihoods as community gardeners. After one year, gardeners are able to manage their plots autonomously and sell their produce directly to the people from the neighbourhood. Along with gardeners’ families, some 650 people benefit from the project by having their livelihood guaranteed.

Context

Challenges addressed

The city of São Paulo is economically and socially divided. The East Zone stands out as grim sprawl of poverty and violence in the municipal context. Poor social conditions, mobility infrastructure, and low economic activity keep it segregated from the rest of the metropolis. Some 3.3 million people (33% of the city’s population) live here. The unstructered growth of the urban sprawl left vacant urban land, subsequently often abused as dump site. Income levels are low. More than 90% of the residents earn less than 1530 R$ (470 US $), and 11% to 35% less than 255 R$ (80 US $) per month (Censo 2010). Often domestic migrants from Brazil's Northeast seeking jobs and income opportunities in the city end up living in this area and doing odd jobs due to their age, poor health, or lack of formally recognised education. Malnutrition and poor physical and economic access to fresh fruit and vegetables have negative impacts on citizens' health, especially on child development.

Location

Process

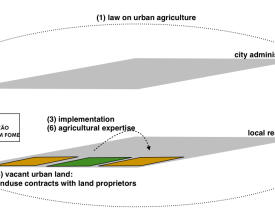

Summary of the process

The Law on Urban Agriculture for the city of São Paulo sets the legal framework within which urban agriculture is actually rendered officially possible (BB 1).

The foundation of Cities Without Hunger as NGO acting on the ground in São Paulo's East Zone closes a gap between city administration and local residents (BB 2).

Visibility of the community gardens, communication among residents and through the media, and guidance through Cities Without Hunger lead to replication: People see and understand the change that is possible within the urban environment (BB 3).

Vacant urban land and landuse contracts for these areas are the prerequisite for the implementation of a community garden (BB 4).

The community gardens are financed through donations and are self-supporting after a one-year implementation phase (BB 5).

Agricultural training courses for project participants as well as potential prior knowledge in agriculture on their side facilitate the implementation of a community garden (BB 6).

Building Blocks

Law on Urban Agriculture for the city of São Paulo

CITIES WITHOUT HUNGER contributed to the passage of a bill on urban agriculture in São Paulo in 2004 (Lei 13.727, de 12 de Janeiro de 2004). By this law, the institutional and legal framework for urban agriculture in São Paulo was created.

Enabling factors

Hans Dieter Temp, founder of CITIES WITHOUT HUNGER, made an effort to push for the implementation of that law, i. a. going to Brasília to support his case.

Lesson learned

The key lesson learnt here is that a well-functioning and transparent communicative connection with governmental institutions is crucial for achieving far-reaching goals of urban planning. The need for urban agriculture projects, though, was recognised by citizens at a local level, whereas the city administration had not realised such action on their own account.

Closing the gap between city administration and local residents

Before he founded Cities Without Hunger, Hans Dieter Temp had worked as project coordinator in the city of São Paulo's public administration, supporting the creation of the Secretaria de Relações Internacionais da Prefeitura de São Paulo, the mairy's secretary for international relations. He found that the effort put into administrative tasks could do little to tackle the actual problems of local people in

the city districts, because the city administration was lacking staff responsible for such tasks, and because residents were lacking basic prerequisites to improve their situation. He wanted to close this gap and to be present on-site as coordinator to support the local network. In December 2003 he quit his job at the city administration and began the foundation process of Cities Without Hunger.

Enabling factors

- on-site experience in the socioeconomic deprived East Zone of the city

- personal contact to residents of the East Zone

- experience in city government and administration allowing for identification of a gap between administrative level and the local level of residents' daily life

Lesson learned

- In order to ensure the efficacy of administrative and governmental action, a close connection to local people is crucial.

- Personal relationships to people whose situation shall be improved by administrative and governmental action can be very helpful in identifying actual needs and starting points for action.

Visibility, communication, and guidance lead to replication

The first community garden was built by Mr. Temp and his brother on their own initiative on a plot of vacant urban land in front of Temp's house in São Paulo's East Zone.

Both have experience in organic agriculture: His brother runs their great-grandfather's farm in Agudo in the South of Brazil, and Temp, after having studied business management in Rio de Janeiro (1985-88), completed a two-years course in organic agriculture on a farm in Tübingen, Germany (1993-95).

The garden area had been abused as a dumping site. When neighbours saw the garden being built there instead, they became aware of and interested in this alternative kind of landuse. A group of people got together to help and to replicate the implementation of gardens. Temp guided them.

Today, having implemented 25 community gardens, he considers guidance crucial for the success of the gardens. Furthermore, this guidance needs to be continuous and intensive especially in the first year of a garden's implementation. Afterwards, community gardeners are able to manage their garden autonomously, but it is important for Cities Without Hunger to be present as contact persons and to lend bigger machines when needed.

Enabling factors

- guidance for the implementation of gardens: practical knowledge and experience in organic agriculture

- visibility of garden in the neighbourhood

- word-of-mouth communication between neighbours spread the word of the possibility to build community gardens

Lesson learned

- interested neighbours need continuous guidance on the ground for the implementation of gardens

- visibility of gardens is crucial for people to understand that alternative landuses are possible, and evoke the desire to replicate these

- gardens are successfully implemented on residents' own initiative rather than using top-down approaches

Vacant urban land and landuse contracts

Vacant urban land is the essential building block required for the implementation of a community garden. The urban sprawl offers spaces where such gardens can be created. Areas include land below electricity lines, near oil pipelines, city-owned land, or private properties.

Cities Without Hunger makes contracts with land owners on the use of the respective area. The land is given to the NGO for free. In turn, land owners can be certain that their land is going to be used as a community garden, avoiding the misuse of areas as dumping sites, and helping prevent wilful damage of infrastructures such as electricity lines or oil pipelines. On such areas, other landuses such as housing are prohibited. That way, landuse conflicts do not occur.

Land use contractors include e. g. the energy supplier Petrobras, Transpetro, or Eletropaulo.

With a growing number of community gardens and strong media presence within São Paulo and beyond, Cities Without Hunger earned a reputation as an NGO with who private and public land proprietors want to collaborate. Hence, getting access to new areas is usually unproblematic.

Enabling factors

- vacant urban land

- land proprietors willing to sign a landuse contract with Cities Without Hunger

- trust in Cities Without Hunger: a good reputation as reliable partner through strong media presence and word-of-mouth both within citizens' circles and the corporate and public realm

Lesson learned

- Due to soil contamination, not all areas within the city can be used for plant cultivation. Hence, it is necessary to take soil samples and have them tested in a laboratory before starting a garden. Gardens will not be built on soil which does not meet the requirements.

- Public relations work with the media, primarily television and newspapers, matters: It helped and still supports the NGO's good reputation.

Financing the community gardens

The implementation of a community garden of about 6000 square metres costs around 33 000 USD. This includes working devices (e. g. spades and hoes), irrigation system and sun protection, measures of soil improvement such as organic fertilizer and humus, construction timber for the compost heap and planting beds, plants, seeds, petrol for the delivery of materials and machines, and personnel costs for two agricultural engineers who help residents create the garden. Costs vary depending on the size of the garden.

The implementation of the community gardens is financed through donations from private and public persons and foundations. In 2015, a German branch was founded in Berlin (Städte Ohne Hunger Deutschland e. V.) with the objective to support Cities Without Hunger's work in Brazil financially and public relations work abroad, especially in Germany, but increasingly at an international level.

After one year, community gardens are self-supporting. Gardeners earn their income selling their produce. Cities Without Hunger still provides technical support and lends bigger machines like tractors when needed. The NGO also supports network-building actions to integrate the gardens in São Paulo's wider economy, e. g. through delivery partnerships with restaurants.

Enabling factors

- Cities Without Hunger depends on donations to finance the implementation of community gardens.

- After one year, the gardens are self-supporting and gardeners earn their livelihoods by selling their produce.

- The NGO keeps providing technical support and fostering socioeconomic integration of the garden projects after the one-year implementation phase.

Lesson learned

- Financing the implementation of the garden projects through donations does not guarantee planning security. If this building block is to be replicated, attention must be given to finding reliable sources of funding.

- Even though community gardeners manage their gardens autonomously after a year, technical support and machines are shared amongst them via Cities Without Hunger. In that resepct, the NGO plays an important role as project coordinator.

Agricultural Training Courses and Prior Knowledge in Agriculture

When implementing a new community garden, Cities Without Hunger offers agricultural training courses to the people interested in becoming community gardeners. Those selected for the projects are often domestic migrants who have come from rural regions to the city in search of employment but have little chances on the regular job market due to their age or education. They often have practical experience in agriculture, which facilitates their activities as community gardeners. Their knowledge is complemented by Cities Without Hunger's agricultural engineers, who train people to run urban community gardens.

Enabling factors

- Cities Without Hunger's team includes agricultural engineers, who support the implementation of community gardens and offer agricultural training courses to project participants.

- Project participants often have a background in agriculture and thus work in a familiar sector as gardeners.

Lesson learned

- It is crucial to offer technical guidance to the people who are to become community gardeners, as the urban realm differs in many respects from the rural one (e. g. plant roots must not exceed a certain length in some areas due to buried pipes or cables, the urban soil must be checkd and enhanced, irrigation systems need to be connected to the city's infrastructure, etc.).

- Prior knowledge in agriculture on the side of project participants facilitates their work as community gardeners and contributes to confidence and self-esteem.

- Even though prior knowledge in agriculture is an asset, it is not necessarily a requirement to participate in the project community gardens. The agricultural training courses offer ample practical learning opportunities and support.

Impacts

Since 2004, Cities Without Hunger has created 25 community gardens in São Paulo's East Zone. Run by a collective of 115 community gardeners, the gardens directly support the livelihood of some 650 marginalised people, including mothers and children. Furthermore, Cities Without Hunger has organised about 50 professional qualification courses, having trained over 1,000 individuals in agriculture or commerce.

The organic mixed culture gardens have contributed to enhancing local biodiversity. Special consideration is given to old or indigenous varieties like arruda or cerejeira, medical plants, flowers, and herbs. As 'green islands' within the city, the gardens improve local microclimate and water regime. Created on abandoned public and private land, e. g. under electricity lines, or on unused areas previously abused as dumping sites, local environment is both embellished and cared for.

The gardens are social spaces fostering communication and social coherence within the neighbourhood. The gardens' substantial lighthouse effect improves the socioeconomic integration of the area: interested parties from city government or other organisations visit them as best-practice examples; or delivery partnerships like the one with pizza restaurant Carlos Pizza from upper middle class Vila Madalena district contribute to this.

Beneficiaries

- People who are marginalised in the labour market due to their age, poor health, or lack of formally recognised education

- People from the neighbourhood whose economic and physical access to fresh produce is limited

Sustainable Development Goals

Story

Agriculture from the country to the city: In search of a better livelihood

Ivone Maria Getúlio coordinates the 3,500 square metre community garden Horta Sapopemba. The garden provides jobs and income opportunities for 13 families from the immediate neighbourhood. Ivone is in her late 50ies. She was born in the municipality of Borrazópolis in the state of Paraná in the Southern Region of Brazil. As a child, she helped out her parents on their small family farm, fed the chicken and pigs, and lent a hand for the work on the fields. She only went to primary school and did not follow further education. As young woman, she moved to the city of Sao Paulo and soon got married. As mother of three children, she stayed at home to take care of her family. Whenever she found an opportunity, she worked as a seller in small shops to support her family's livelihood. She would also gather disposable materials like PET bottles and cardboard on the streets and sell them to recycling cooperatives.

The plot of land where the community garden is implemented today used to be a desolate area bordering a favela above an oil pipeline. Big signs saying "ATENÇÃO – Dutos Enterrados – Não acender fogueiras – Não jogar lixo ou entulhos" (ATTENTION – Buried Pipelines – Do Not Light Fire – Do Not Dump Waste or Rubble) are reminders of the city's uncontrolled sprawl.

In order to implement a community garden here, CITIES WITHOUT HUNGER concluded a contract for the area's use with the proprietor, petroleum supplier Transpetro. Crucial for the agricultural cultivation of this area is CITIES WITHOUT HUNGER's technological know-how, since plant roots must not exceed a certain length due to the oil pipeline. Within a year, the organisation brought together a group of local residents who, similar to Ivone, sought to find jobs and income opportunities allowing for a dignified life for themselves and their families. Supported by the NGO's expertise, agricultural training courses, and machines, they prepared the soil, planted and sowed. Within a year, the garden became self-supported, managed by Ivone. The community garden gave Ivone a new perspective, not least because she is able to work in an area she knows a lot about from her childhood. "I grew up in agriculture. The community garden is my life. It nourishes me and my family and gives me great joy", she smiles.