Hunter and Community-Based Early Warning System Expands Ebola Mortality Monitoring in Great Apes

In northern Republic of Congo, hunters and community members were recruited to report morbidity and mortality events in wild animals. In the region, great ape die-off events were found to precede human cases of Ebola virus disease. Through the community engagement program, reporting channels were developed, relaying information from small villages to connector communities via radio, messages carried by commercial drivers or other contact routes with national authorities. This facilitated information flow to veterinarians so that diagnostic sampling could occur within the short timeframe needed before carcasses degrade. Reporting of events expanded the surveillance system to empower local people and allowed for early warning through sentinel surveillance for possible disease threats to humans and wild animals. Accompanying community outreach also helped to raise awareness about the dangers of hunting certain species or eating animals found sick or dead, particularly in epidemic periods, thereby promoting safer practices.

Context

Challenges addressed

Subsistence hunting provides a critical protein source for communities living in parts of Central Africa, and extractive industry concessions have resulted in increased access to forest areas. Given the endangered status of some animals in the region, hunting could be at odds with the goals of conservation. An opportunistic finding of a wild animal carcass was often viewed as good luck, reducing the physical effort needed for a hunt. Additionally, integration in modern healthcare systems was limited, partially due to the remote location. Suspicion and superstitions in the region also affected perceptions and practices. This program worked to engage communities and hunters in an early warning system, expanding animal mortality monitoring and creating awareness to reduce disease risk to humans and animals. To avoid inadvertently incentivizing hunting, no compensation was issued for reporting; instead, the importance of information from carcass reporting was emphasized in regard to community wellbeing.

Location

Process

Summary of the process

Stakeholder engagement and participation was a crucial part of the early warning system. Event reporting by hunters provided ongoing monitoring information that would not otherwise be available, helping to make the early warning system robust and inclusive of multiple species for a true One Health approach. At the same time, having a formal system in place provided the technical infrastructure for field and laboratory investigation of mortality reports, with public and animal health action as needed. Awareness of the risks posed by sick and dead animals not only helped to protect individuals involved in hunting, but likely also increased broader community support in the case of needed management actions.

Building Blocks

Early warning system

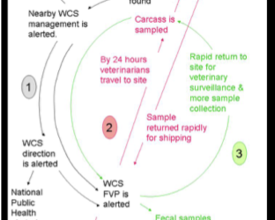

Components of the system involved mortality reporting by hunters and community members, investigation of reports by veterinarians trained on specimen collection and handling protocols, specimen transport to national laboratories, and laboratory screening for disease diagnostics. Each of these involved specialized inputs, but the coordination between entities created the system. Information management and communication were conducted throughout the process. A Carcass Data Collection and Reporting Protocol was integral to the process, ensuring consistent reporting.

Enabling factors

- A local team, supported by a global program, ensured continuity of the broader Animal Mortality Monitoring Network and technical expertise to develop and implement disease investigation protocols

- Full integration and support of Congolese government officials from multiple ministries helped prioritize the animal-human link for public health and conservation outcomes

- Availability of functional national and international laboratories and the ability to move specimens rapidly, including from remote areas, supported diagnostics in endangered species

Lesson learned

In this setting, hunters and some community members were the key eyes on the ground for wild animal mortality detection, having some of the only human presence in forest areas where carcasses may degrade rapidly, providing a limited window for detection and investigation. While the overall Animal Mortality Monitoring Network included a broader scope of reporting, only reports meeting certain criteria (such as being a great ape species, the extent of carcass degradation, and other factors) prompted disease investigation, keeping the scale of the program feasible and cost-effective. Unfortunately, despite its demonstrated value, sentinel detection in wild animals is not routinely a formal part of public and animal health surveillance in many parts of the world, missing a critical source of potential information that could promote early warning for disease threats in humans and other species. Training was also an important component of the project, including on biosafety protocols for safe disease investigation and diagnostic screening.

Stakeholder engagement and participation

Program personnel visited villages in areas considered at-risk for Ebola virus outbreaks. This engagement helped to identify community interest in contributing to animal mortality reporting and assess the potential role of hunters in the network. While researchers and ecoguards initially provided some reports of carcasses, the majority of reports were ultimately received from hunters, allowing for more focused engagement of this demographic group. In addition to reporting, outreach was conducted to reach hunters and communities in several ways to support awareness of risk reduction strategies. For example, in the Étoumbi region, the Field Veterinary Program provided outreach education on Ebola and livestock husbandry to the Étoumbi Hunters’ Association, as well as hunters and other villagers of Mbomo and Kellé. Communities around national parks (Nouabalé-Ndoki and Odzala-Kokoua) were engaged, and visual posters and books were also provided to a village nurse for further dissemination.

Enabling factors

- Long-term efforts in the region fostered trusted relationships with the community that likely facilitated successful engagement and participation.

- Sensitivity to the needs and priorities of local stakeholders, including food security and cultural traditions, promoted practical solutions that supported buy-in and uptake.

- The reporting process established clear channels for information flow, minimizing the burden for community participants providing reports while ensuring information was communicated from local to national levels.

Lesson learned

This program was initiated in 2005. There may be updated regulations regarding hunting and other subsistence or commercial use of wildlife in the region that could affect practices, and additional technologies (e.g. vaccination) are now available that could change the management strategies for humans and potentially wild animals in the event of Ebola virus or other disease detection. However, the program reinforces the utility of locally-relevant approaches and solutions, as well as the role of involving stakeholders that may be perceived as far outside of the conservation or public health sectors. In this case, hunters and community members living in Sangha district were among those at greatest risk of exposure to infection from handling carcasses, making their awareness and engagement in risk reduction practices critically important. Given the importance of food security and cultural traditions, top-down approaches were and likely still are unlikely to be effective, instead requiring stakeholder engagement and locally-accepted solutions.

Impacts

In the early 2000s, Ebola virus was recognized as a major threat to health and survival of Central African great apes, with thousands of gorilla deaths associated with the virus. Ebola outbreaks were also being recorded in human populations, with reports of mortality in great apes preceding human cases. The opportunistic collection of carcasses by hunters, particularly during epidemic or epizootic periods, put their communities at heightened risk of infection. With government authorities responsible for health and wildlife, an Animal Mortality Monitoring Network was leveraged to enhance detection of Ebola virus via disease investigation of carcasses reported by hunters and community members. Engaging hunters helped reduce the practice of carcass collection for food or income and facilitated new information coming into the surveillance system for early warning for possible disease threats. Over the course of several years, dozens of carcasses were sampled. The relatively high participation of hunters – who generated the majority of reports – was a sign of trust built with this stakeholder group. In concert with ecological surveys and fecal sample screening, the program generated information to monitor and help reduce potential for spread among endangered great ape and human populations.

Beneficiaries

- Communities

- Great apes

- Human and animal health system

Sustainable Development Goals

Story

The connections between Ebola virus, great apes, and humans made apparent to me the need for a holistic approach, and in a Washington Post interview the term “One Health” was borne out of a quote I gave that "Human or livestock or wildlife health can't be discussed in isolation anymore…There is just one health. And the solutions require everyone working together on all the different levels." The term has since gained traction globally, but at its core it reminds us that many stakeholders can play a role in improving health outcomes for humans, animals, and the environment. This program successfully demonstrated how a One Health approach could be put into practice in a local context, expanding the benefits of conservation programs to generate information also important for public health. The effective engagement of local stakeholders allowed for buy-in, while respecting the needs and values of the communities we were working with. As head of the Field Veterinary Program, it was also rewarding to work with colleagues and friends such as Dr. Alain Ondzie and Dr. Jean-Vivien Mombouli, seeing them grow in their roles and make such significant contributions to wildlife and human health.