Loon Translocation

In 2013, BRI began one of the largest loon studies ever conducted. The initial 5-year scientific initiative, Restore the Call, aimed to strengthen and restore Common Loon populations within their existing and former range. Through this research effort, BRI has developed detailed translocation protocols and practices. This method of loon restoration can be replicated in ongoing and future projects.

Context

Challenges addressed

This scientific initiative laid a strong foundation to help researchers identify major threats to loons and to create solutions that strengthen populations and to restore loons to their former breeding range.

Location

Process

Summary of the process

Translocation involves multiple teams conducting source population surveys, capture and transport, and the difficult task of safely rearing the chicks, with numerous steps and processes in between. The major steps to develop a viable translocation and restoration process: 1) identify the restoration site and source populations; 2) safe capture and transport of loon chicks; 3) develop plans and equipment for captive rearing; 4) release chicks once they are ready to feed on their own; 5) monitor chicks until they fledge; 6) monitor for returning adult loons; and 7) plan for restoration.

Building Blocks

Identify Restoration Sites and Source Populations

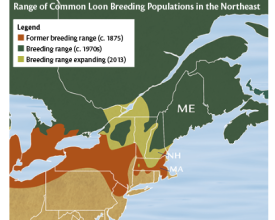

In 1974, New Hampshire marked the southern edge of the range for Common Loons, and at the time that range was retracting. Recovery efforts carried out by loon conservation groups in New Hampshire and Vermont helped restore loon populations in those states.

In Massachusetts, extirpation has made recovery in that state much slower. Currently, loon recovery in Massachusetts is still dependent on breeding success in northern New England and New York. BRI’s translocation research being carried out in Massachusetts provides an example of how a population at the edge of its range can be restored.

Enabling factors

Working with state and local agencies as well as lake landowners helped facilitate the process of identifying restoration sites and source populations.

Lesson learned

Initial planning is critical to success.

Resources

Capture and Transport

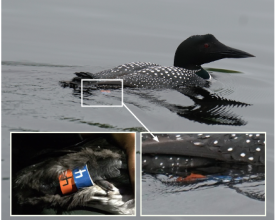

Using traditional nighttime techniques, BRI researchers captured chicks 5-8 weeks old from source lakes. Once chicks are in hand, a BRI attending veterinarian performs a physical examination and administers fluids to prevent dehydration during transport.

Enabling factors

Extensive knowledge and expertise in capturing and determining age of chicks.

Innovative techniques to transport the chicks long distances. To keep chicks calm and healthy enroute to the relocation site, BRI staff designed vented containers fitted with suspended mesh netting to protect the loon’s keel and feet and to allow excrement to fall through.

Lesson learned

The transport carriers reduce the risk of injury during long trips and help preserve feather quality. Cold packs beneath the mesh help chicks from overheating.

Resources

Captive Rearing of Loon Chicks

Translocated loon chicks are raised in specially designed aquatic pens until they are old enough to feed on their own (9-10 weeks old).

Enabling factors

The BRI team devised an innovative technique to monitor and feed the loons without being seen, which ensures that the chicks do not become habituated to humans during the rearing process.

Lesson learned

Feeding chicks in captivity was a trial and error process. Finally, researchers figured out that the sound of the splash made by the fish when a parent loon dropped food next to the chick was the catalyst for the chick to go after the fish.

Resources

Release and Monitoring

Chicks are reared for various lengths of time depending on age and how well they acclimate to the pen. Prior to release to the wild, chicks are given a full health assessment, and banded with a unique color and number combination.

Once released, chicks adapt quickly, foraging on their own almost immediately. BRI biologists monitor the chicks daily when first released, then weekly until they fledge.

Enabling factors

Making sure the chicks are healthy and well fed before releasing them. A wildlife veterinarian is on staff.

Lesson learned

Closely monitoring is critical to be sure of the chick's health, but to learn more about loon ecology.

Loon chicks acclimate quickly to the wild.

Monitoring for Returning Adults

A total of 24 Common Loon chicks were successfully moved from New York and Maine to southeastern Massachusetts as part of BRI’s Massachusetts loon translocation project conducted from 2015-2017 --

- 15 were reared in aquatic enclosures before being released onto Pocksha, Assawompset, or Little Quittacas Ponds (APC).

- 9 older chicks were directly released after being transported.

In 2017, an immature loon chick translocated the previous year was re-confirmed on the APC, marking the first record of a loon chick returning to the release site after its release year.

As of spring 2020, nine adult loons returned to the lakes in Massachusetts to which they were translocated and captive-reared, and then from which they fledged. Their return marks a major milestone in the efforts to translocate Common Loons.

Enabling factors

Translocation involves multiple teams conducting source population surveys, capture and transport, and the difficult task of safely rearing the chicks, with numerous steps and processes in between.

Lesson learned

This is a long-term study and needs careful thought and planning throughout the process. The most important factor is the health of the wildlife.

Restoration

Restoration using translocation methods helps jumpstart breeding loon populations in areas within their former range, such as the Assawompset Pond Complex (APC) in southeastern Massachusetts shown above. The APC, comprised of at least 11 lakes that are suitable for breeding loons, was historically an important breeding area for loons in the state.

Great Quittacas Pond was the site of one of the last known nesting loon pairs before their statewide extirpation in the early 20th century. Although breeding loons returned to Massachusetts in 1975, their recovery is primarily limited to the north-central part of the state.

Enabling factors

Lakes and ponds in the APC and nearby areas fulfill the criteria for high quality loon breeding habitat including: clear, clean water; abundant populations of small fish for prey; and shoreline habitat with coves and islands to provide suitable nesting areas. For these reasons, we estimate that at least 20 nesting pairs could occupy the APC surrounding area lakes in around 30 years. This population would thereafter form the basis for further recovery in the southeastern part of the state.

Lesson learned

Loons can be translocated to new breeding areas.

Impacts

Translocation: Expanding the Range of Common Loons in Massachusetts

In 1974, New Hampshire marked the southern edge of the range for Common Loons, and at the time that range was retracting. Recovery efforts carried out by loon conservation groups in New Hampshire and Vermont helped restore loon populations in those states.

In Massachusetts, extirpation has made recovery in that state much slower. Currently, loon recovery in Massachusetts is still dependent on breeding success in northern New England and New York. BRI’s translocation research being carried out in Massachusetts provides an example of how a population at the edge of its range can be restored.

Beneficiaries

Loon Conservation -- the Common Loon is an important bioindicator of the health of an ecosystem including fish and wildlife. People often share lakes with loons. This work will advance our understanding of loon ecology.

Story

Story in Audubon Magaine: https://www.audubon.org/magazine/winter-2020/an-innovative-effort-return-loons-massachusetts

Welcome Home Loons

New recovery techniques have helped the iconic waterbirds nest in Massachusetts' glacial lakes for the first time in more than a century.

Loons were once an iconic presence in the state’s glacial lakes. In Walden, Thoreau recounts playing hide-and-seek with the bird—its “demonic laughter” gives away its position. But a few decades later, due to deforestation, pollution, and human persecution, loons were gone from the state.

BRI's research efforts returned breeding loons to Massachusetts. In spring 2019 a male loon translocated from New York (in 2015) met a female, and in June of 2020, the pair hatched a bonafide hometown chick—the first known in the southern part of the state in more than a century.