Public participation to strengthen and legitimize planning processes

This solution ensured the local communities were actively engaged throughout the most recent planning process for the GBR Marine Park. Going above and beyond what is normally required for public engagement in the legislation guaranteed high legitimacy for this planning process. It also provided detailed information for the park planners, and facilitated the engagement of many others (locally, nationally or internationally) which subsequently led to a better planning process overall.

Context

Challenges addressed

Ensuring the wider community is actively engaged throughout the planning process. The process for public participation when preparing a Zoning Plan in the GBR is set out in the legislation and is a requirement to legitimize the planning process. The most recent public participation process exceeded expectations and led to challenges like an unprecedented number of public submissions, mis-information, unrealistic expectations and the silent majority.

Location

Process

Summary of the process

These building blocks outline how effective public participation is an important part of achieving a good outcome in any planning process. Dealing with written public submissions is discussed in BB1, including receipting submissions and coding the information. A focussed form for submissions is also suggested to assist both submitters and planners (while not precluding any other information that anyone may wish to submit). BB2 discusses how to deal with those who do not write a submission (the ‘silent majority’) but who still have interests in the planning area. Further aspects for effective public participation are also discussed, including:

- possible ways to address deliberately distorted or mis-represented information (BB3);

- the benefits of continuing public engagement throughout the process and why this is more effective (BB4);

- the value of preparing targeted educational material but also the essential need to ensure the planning team has a good understanding of the various industries who may be affected (BB5);

- the critical role of politicians and the need to have them engaged throughout the planning process rather than involving them only at the end (eg. when hoping for legislative ratification) (BB6).

Building Blocks

Written public submissions during the planning

Given that GBRMPA had previously never received so many public submissions (> 10,190 in the 1st phase and 21,500 in the 2nd phase commenting on the draft zoning plan), the following multi-stage process was used to analyse all the submissions:

- Contact details from each submission were recorded in a database, a unique identification number was assigned, and an acknowledgment card was sent to whoever made the submission.

- All submissions were individually scanned and the electronic files were saved into an Oracle submissions database.

- Trained GBRMPA staff analysed each submission using a coding framework consisting of keywords for a range of themes and attributes. The framework was developed from a stratified random sample of submissions based on place of origin and sector. The database linked the scanned PDF with the relevant contact details and analytical information (i.e. keywords)

- A search and retrieve ability based on the keywords enabled planners to search and retrieve PDFs of specific submissions or to run various queries of all the information in the submissions.

- Many submissions involved spatial information, including some 5,800 maps in the formal submission phases; these maps were digitized or scanned.

Enabling factors

The legislation outlines a comprehensive process for community participation in the planning process. The fact that the locals were ‘familiar’ with two phases of public participation and written submissions from previous experiences with GBR planning processes did assist this most recent planning process. Many groups assisted by submitting joint submissions. Consistency of analysis across the analytical team was ensured by the team leader checking a sample of the analysed submissions.

Lesson learned

- The analysis method must consider the substance of submissions rather than the number of times a comment is made. The submission process is not a numbers game but more about the quality of any argument that is made.

- In the first public phase, many open questions on the submission form led to long rambling answers; these proved hard to code, as were the large maps that were also distributed.

- The 2nd phase was more effective as a simple two page A3 size submission form asked more specific questions. Not everyone used the submission form, but it did make scanning and coding easier.

- Many pro-forma submissions were received; easy to code but not helpful.

- Linking spatial information with a qualitative coding system in the GIS was important.

- Coding was based on seven key themes and a range of sub-themes, allowing a detailed analysis of each submission and all information provided.

- Public feedback is important to demonstrate that all comments were considered.

Assessing the views of those who don’t want to get involved

It should not be assumed that all those who have an interest in an area or the planning process will necessarily provide a written submission. Around 1 million people live adjacent to the GBR and many millions of people elsewhere in Australia and internationally are concerned for the future of the GBR. However the 31,600 written public submissions represented only a small proportion of all those concerned citizens (noting many individual submissions were prepared on behalf of groups representing many hundreds of members). At many public events during the planning or in the media, it was a small ‘noisy minority’ who dominated the discussions. Different techniques were therefore applied to determine the views of the ‘silent majority’, many of whom were interested or concerned but did not bother to write a public submission. This included commissioning telephone polling of major population centres elsewhere in Australia to determine the ‘real’ level of the wider public understanding and support. In addition, community attitudes and awareness were monitored through public surveys. These showed that many stakeholders were misinformed about the key issues/pressures and what could, or should, be done to address their concerns.

Enabling factors

Telephone polling in major population centres around Australia is an approach used by political parties for political purposes. The same polling companies who undertake these surveys were used in the rezoning, with the planners working closely with them to determine the most useful questions. The results helped politicians to understand the wider public perspective, not just the noisy minority or the media reports. Community attitudes were also monitored through public surveys.

Lesson learned

- Don’t ignore those stakeholders who choose to remain silent.

- Remember that politicians are usually more interested in what the wider community thinks than just those who send submissions.

- Recognise the ‘noisy minority’ usually does not represent the silent majority comprising all those with an interest in the future of the MPA.

- Public meetings are often dominated by a few – ways are needed to allow wider concerns to also be heard.

- Some stakeholders ‘leave it to others’ to send a submission – either because they think everything is fine, or else they believe changes are unlikely and so are not motivated to act.

- Telephone polling of the wider public or internet surveys can determine the real level of understanding and support.

- Tailor your key messages for different target audiences (take a strategic approach).

- Monitor wider community attitudes and awareness through media analysis, via the internet (e.g. Survey Monkey) or face-to-face interviews or surveys.

Correcting misinformation and unrealistic expectations

During any planning exercise, some key messages or information may become deliberately (or inadvertently) distorted or mis-represented by those who are opposed to the process. Many people believe everything they hear (without always checking the accuracy) and are also suspicious of any changes proposed by bureaucrats. Every time these concerns are passed onto others, they are embellished, leading to distortions from the original facts. Furthermore some stakeholders selectively quote from ‘research’ when it suits their concerns whilst ignoring evidence with a contrary position. Some stakeholders have unrealistic expectations and do not understand what is possible, or impossible, as part of the planning process. Unless this misinformation is addressed, the public may only hear the distorted or unclear messages which may then become reinforced by others with similar perspectives. Such misinformation, and the consequent fear and uncertainty, resulted in some of the largest public meetings during the GBR planning process. To counter some of these problems and address unrealistic expectations, GBRMPA produced a fact sheet titled ‘Correcting the mis-information’ - this was widely distributed, especially at large public meetings.

Enabling factors

During the rezoning, the scientific experts were unable to provide 100% certainty. They did, however, provide a strong scientific consensus for the recommended levels of protection based on theoretical and empirical evidence. In doing so, they also took into consideration:

- the national and international expectations associated with managing the GBR, the world’s largest coral reef ecosystem; and

- international experience and opinion advocating increased protection of the world’s oceans.

Lesson learned

- Many stakeholders were initially misinformed about what were the key issues and pressures and what was needed to address them.

- People needed to understand: there was a problem with biodiversity before they would accept that a solution was required (i.e. a new zoning plan was needed); that the rezoning was not about managing fisheries, but about protecting all biodiversity; to focus on the problem (protecting biodiversity) rather than on what the consequences might mean (i.e. reduced fishing areas).

- Be prepared to refute contrary claims and correct misinformation, irrespective of whether it is due to a misunderstanding or deliberate mischievous behaviour – and address it as soon as possible (leaving misinformation out in the community just exacerbates the issue).

- A lack of perfect data or lack of 100% scientific certainty may sometimes be given as reasons to delay progress or to do nothing; but if you wait for ‘perfect’ data, then nothing will ever happen.

Ongoing/continuing public engagement during the planning

The GBR legislation mandates 2 formal phases of public engagement when planning – one seeking input prior to developing a draft plan, and the second to provide comments on that draft plan. However previous planning processes in the GBR demonstrated that public engagement was more effective if undertaken throughout the process. This included the preparation of various brochures, technical information sheets (some tailored for different target audiences), periodic updates (see Resources below) and graphics explaining concepts like connectivity. Throughout the planning process (1999-2003) the public were engaged by a variety of methods e.g. newspapers, radio, TV, the website (refer Resources below). Planners knew a revised plan was needed. However, communication experts pointed out that the wider public did not understand why a new zoning plan was needed when there already was an existing plan. Rather than progressing the new draft plan, communications experts advised the planners to pull back for several months to conduct an awareness campaign called “Under Pressure”. Once the public were more aware of the problems facing the GBR, they were more accepting of the need for a new plan but also understood they could have their say.

Enabling factors

The supporting role of experts in public education and communications was critical throughout the planning program. These specialists are experts in public engagement, so their perspective on a number of issues (e.g. ensuring the public understood the problems facing the GBR and why a new plan was necessary) was invaluable during the GBR process. Keeping the public informed and on-side using a range of methods were key components for success before, during and after the planning program.

Lesson learned

- Public engagement was more effective when undertaken throughout the planning process.

- The ‘Under Pressure’ campaign was successful in raising public awareness as to why a new plan was needed.

- The support from communications experts throughout the planning program is invaluable.

- The periodic updates were useful to keep the public informed of progress between the formal engagement periods.

- The media can be a great/influential ally – or a potent opponent. Work closely with all forms of local media so they get to know you and how you work.

- A trained media spokesperson in your team who knows both the topic and how to present well is important.

- Expect that some media will be critical or opposed to what you are doing – and be prepared to counter those views with clear and concise messages.

- Keep a running list of all meetings/engagement events and the numbers present – politicians are usually interested to see how many people you have engaged.

Targeted educational material

Throughout the GBR planning program, targeted educational material was prepared and widely distributed. For example the map of the 70 bioregions across the GBR was a key foundational document upon which a lot of subsequent public engagement was based. The preparation of Technical Information Sheets (see below) helped to explain concepts like ‘biodiversity’ in layman’s terms as many people did not understand what it was nor its importance. Similarly trying to explain the importance of ‘connectivity’ in the marine environment was greatly enhanced by a poster entitled ‘Crossing the Blue Highway’ (see Photos below). It used a combination of digital art, photos and words to explain the importance of connectivity between the land and the sea, and within habitats of the GBR - this reinforced the need for the ‘representative’ approach to the zoning. Different stakeholder groups have differing interests so the communication messages were appropriately tailored by experts who understood the sectors e.g. what was presented to fishers was different to how a very similar message was presented to researchers or to politicians.

Enabling factors

Having experts within the planning team who understood the issues facing the key sectors proved invaluable:

- For ‘tailoring’ key messages (e.g. an ex-fisheries manager really understood the concerns of all types of fishers; an ex-tourism employee knew what was important for tourist operators; Indigenous persons in the team helped engagement with Indigenous groups).

- Having a good understanding of each industry was also reassuring for those who felt their livelihoods might be affected.

Lesson learned

- Many stakeholders initially were misinformed about the key issues and what could, or should, be done.

- People needed to understand there was a problem before accepting that a solution was required and that new zoning was necessary.

- It is essential to tailor key messages for different target audiences – a blend of technical and layman’s information was produced and made widely available.

- Having experts on the planning team who could tailor information relevant to the various stakeholder sectors was critical.

- The rezoning was not about managing fisheries, but rather about protecting all biodiversity.

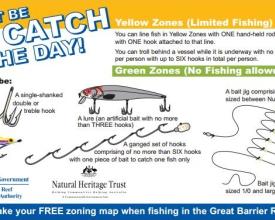

- The use of graphics to explain complex issues like ‘connectivity between habitats’, or the legal definition of ‘a hook’, proved invaluable to educate a range of audiences.

- Some elements of how GBRMPA undertook public participation/education were more successful than others (e.g. minimising public meetings whenever possible), so learn from other’s experience.

Engaging politicians and champions throughout the planning

It is important to engage the key political players from the start of the planning process rather than wait until nearer the completion of any such process. Soon after the start of the GBR planning process, a formal ‘Leader’s Guide’ was delivered to all State and federal politicians along the GBR coast and wherever possible, personal briefings were undertaken by senior GBRMPA staff. This helped ensure all politicians had the correct information, had extra materials to give to their constituents and had a contact within GBRMPA if further information was required. While some decision-makers would prefer all planning decisions to be consensus-based, or achieve a ‘win-win’ for all concerned, neither consensus nor ‘win-wins’ are achievable goals for stakeholder processes dealing with issues of such magnitude and complexity as most MPA planning processes. In the GBR, it was important to explain to politicians early in the planning process that compromises were the expected outcomes. At the end of the GBR rezoning, no one stakeholder group felt they got exactly what they wanted; but every group knew they had ample opportunities to become engaged and to provide input – and most understood the compromises all sectors had made.

Enabling factors

The formal ‘Leader’s Guide’ delivered to all politicians along the GBR coast ensured they had the best available information and a person to contact within GBRMPA for further information. Maintaining contact with the key political players throughout the planning process was also invaluable and paid dividends when the final plan was presented to parliament. The use of telephone polling (outlined in Building Block 2) was invaluable to demonstrate the wider public views to politicians.

Lesson learned

- Do not raise false expectations with stakeholders or politicians as to the likely outcomes.

- Consensus and ‘win-wins’ for all those concerned in MPA planning processes are unlikely to be achievable goals when dealing with issues of such magnitude and/or complexity.

- The timelines favoured by politicians are often not compatible with comprehensive planning processes.

- Compromise is essential – but recognise that this is considered by some to be winners and losers.

- The use of ‘Champions’ (e.g. sporting heroes, national identities) to endorse the planning process or deliver key messages is helpful to raise the planning profile.

- At the end of the day, almost all planning processes are political, and whether planners like it or not, there will be political compromises imposed at the end of the process – how much your political masters are aware of the issues, the implications of the recommended plan and the full range of public views will help them make the best possible decisions.

Resources

Impacts

Significant changes were made between the draft zoning plan and the final zoning plan, primarily due to high levels of public participation. Many of the modifications to the draft resulted from the detailed information provided in public submissions and from other information received during the planning process. The final zoning plan came into effect in July 2004 and achieved its objectives; it protected the range of biodiversity of the GBR in a way that minimized the impact on the users as far as was practicable. The final plan included many compromises and no one group got exactly what they wanted; everyone felt somewhat aggrieved. However, there was also widespread recognition that the public input had effected huge changes during the planning process and everyone had multiple opportunities to have their say. The high levels of community involvement and visibility of the process due to media attention ensured that members of parliament were well aware of the extent of public participation and the significant changes that occurred between the draft and the final plan. Media attention, interest-group lobbying and government involvement all lead to legitimacy, not only for the plan, but also for implementation and enforcement.

Beneficiaries

Planners and local communities, and everyone with an interest in the future of the GBR

Story

To facilitate and encourage public participation, the GBRMPA embarked on a comprehensive community awareness campaign. Considering the interest in the GBR at local, national and international scales, the consultation program was designed and conducted to reach all interested groups, but with a focus on local communities. During the two formal phases of community participation, staff visited every major town adjacent to the GBR and conducted over 600 meetings in some 90 locations, with thousands of people attending. During these consultation periods, the GBRMPA distributed thousands of submission brochures and there were over 2,000 media items in newspapers, on TV and radio, and on the web. In addition, there were hundreds of other meetings, update newsletters and other communications outside the two formal consultation phases. The GBRMPA knew that the rezoning of the Marine Park would generate public interest. However the level of interest far exceeded expectations. What eventuated was the most comprehensive process of community involvement and participatory planning for any environmental issue in Australia’s history. The 31,600 written public submissions received - 10,190 in the first formal phase and 21,500 in the second phase commenting on the draft zoning plan - were unprecedented compared to previous planning programs in the GBR. All these comments necessitated the development of faster and more effective processes for analysing and recording the information that was received by the GBRMPA. A large number of submissions involved spatial information, including some 5,800 maps in the second formal phase alone. The GBRMPA considered, coded, and analysed all submissions, including this spatial information, and digitized or scanned the maps. Many modifications were made to the draft plan - in some locations, limited options were available to modify the proposed no-take areas, particularly in inshore coastal areas, while still achieving the recommended minimum levels of protection. In November 2003, the revised zoning plan and a regulatory impact assessment were presented to the federal minister and tabled in the Australian Parliament. At this time, the federal government also introduced a Structural Adjustment Package to assist fishers, fishery related businesses, employees, and communities adversely affected by the rezoning. The final zoning plan achieved its objective of protecting the range of biodiversity and formally came into effect 1 July 2004