Reintroduction of the red-billed chough (Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax) to Jersey, Channel Islands.

Red-billed choughs (Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax) are a rarity in the British Isles having a fragmented population of less than 500 breeding pairs. Choughs died out in Jersey, a British Channel Island, at the turn of the 20th century after changes in agricultural practices led to a drastic loss of food sources (i.e. soil and dung invertebrates). Egg collecting and farmers’ general discrimination against corvids also impacted numbers.

Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust managed several soft releases of captive-bred choughs (2013 to 2018). Continued post-release veterinary care, close daily monitoring, supplemental feeding, and stakeholder engagement have all contributed to the success. After an absence spanning a century, Jersey once again has a resident chough breeding population and conservation grazing in action along the north coast.

Choughs are the flagship species for a multi-partner project, Birds On The Edge, which aims to restore Jersey’s depleted coastland bird populations through habitat management.

Context

Challenges addressed

- Lack of suitable foraging habitat to maintain a viable chough population. Only 18% of Jersey’s land cover is natural vegetation the majority of which is dominated by bracken.

- Limited captive-breeding success at Jersey Zoo resulted in (1) a reliance on importing birds from a UK zoo, (2) a reduced capacity to select suitable candidates for release, (3) releasing sub-adults and adults in the first cohort, not juveniles (<6months old) which are more manageable and adaptable to change.

- Choughs are an intelligent, social species quick to learn when not under stress. Recapture techniques for the initial releases and continued post-release management constantly change as the birds learn how staff operate, e.g. which side of the aviary the release hatches are operated from, and try to evade capture.

Location

Process

Summary of the process

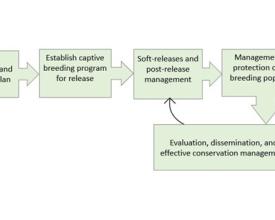

The success of the reintroduction to date has required five key components. The first step was a feasibility assessment to ensure a reintroduction was the most appropriate tool. Once established, a clearly defined plan was developed and implemented involving captive breeding for release, soft releases over several years and intensive post-release management.

Durrell’s commitment to restoring the species continued after the birds began breeding in the wild. Support for the population now consists of nest management and protection as well as supplemental feeding and veterinary assistance if needed.

Throughout the reintroduction, there has been a continuous need to evaluate and feedback into the management of the releases and the breeding population. The future of the population and the effectiveness of the wider Birds On The Edge objectives will rely on analysis, evaluation, and continued commitment by the project partners, stakeholders, and Jersey islanders.

Building Blocks

Assess feasibility and develop a strategic plan

Jersey farmland bird transects have been conducted by Durrell staff, partners and volunteers since 2005. This data combined with other datasets highlighted declining population trends leading to the publication of The Conservation Status of Jersey’s Birds.

In 2010, a partnership between Durrell, the National Trust for Jersey, and the Government of Jersey established Birds On The Edge, a conservation initiative to restore depleted coastal farmland bird populations. The reintroduction of chough acting as a driving force to implement change.

Feasibility studies supported the need to reintroduce chough; natural colonization was not a feasible option. They also identified a release site at Le Don Paton on the north coast. The National Trust for Jersey introduced a free-ranging flock of Manx loaghtan sheep to graze the site ensuring the birds had natural foraging habitat once released. The National Trust also purchased adjacent agricultural fields to avoid any land management conflicts and to sow conservation crops (another component of the initiative).

A reintroduction plan was created following IUCN Guidelines for reintroductions and other conservation translocations. This document assisted in securing licensing for the release, initial funding, and provided a way of clearly communicating intentions to stakeholders.

Enabling factors

- Accessible baseline data to make informed decisions.

- Visionary and experienced project leaders.

- Existing guidelines for a reintroduction.

- Land ownership by a project partner makes it easier to determine and carry out management decisions.

- Jersey is a small island with relatively less bureaucracy than other countries and a smaller network of players.

Lesson learned

There is a lack of baseline data for habitat quality pre-grazing and pre-reintroduction particularly habitat mapping and invertebrate biodiversity. This is evident when evaluating the success of Birds On The Edge and assessing the long-term needs of the reintroduced chough population. With hindsight, more could have been done.

More formality between the Birds On The Edge partnerships would help with strategic planning, clarity for donors, and improve communication and outreach. There is no contracted position to oversee the management of Birds On The Edge. There is no team specifically dealing with marketing and education which has limited the effectiveness of our outreach, especially with social media an increasingly important tool for engagement and funding resources.

Establish a captive breeding program for release

Paradise Park loaned two pairs of choughs to Jersey Zoo in 2010 to begin a captive breeding program. To establish a wild population, it was estimated 30 to 50 juveniles needed to be released over a 5 to 7-year period. Any shortfalls in numbers would be supplemented by importing juveniles from Paradise Park.

Jersey Zoo transformed two aviaries into dedicated breeding aviaries and created a display aviary to house the flock over winter mimicking natural behavior. Nest boxes were fitted with cameras for remote monitoring. Nestlings are susceptible to aspergillosis and nematode infections in captivity. Cameras allow staff to monitor for clinical signs and intervene as soon as possible to ensure survival.

Paradise Park, with decades of experience breeding choughs, provided guidance, training, and financial support. Jersey staff spent time behind the scenes at Paradise Park to learn about chough husbandry reciprocating once the release was underway with staff from the UK visiting Jersey.

Despite releases ending in 2018, Jersey Zoo continues to breed chough in captivity providing a backup in case there is a renewed need to release. It also allows a conservation message to be communicated to the public through educational talks at the display aviary. Surplus juveniles are returned to Paradise Park’s breeding program.

Enabling factors

- A support network of skilled and experienced conservationists enabling efficient planning with the ability to adaptively manage.

- Strong partnerships with a commitment to succeed.

- An enthusiastic team willing to go above and beyond for the species.

Lesson learned

- Initial breeding success was limited for various reasons one being incompatibility and/or inexperience of breeding pairs. Inexperience was initially a problem with the keepers as well. Not with techniques, but with nuances of the species which was why learning from others and a willingness to try different things is crucial.

- Double-clutching is not documented in wild choughs but is possible in captivity and could be an effective tool for increasing productivity.

- Choughs are intelligent and quick to learn. This can be problematic for management, e.g. learning to avoid entering catch-up enclosures. On the other hand, it can be beneficial if exploited, e.g. crate trained.

Soft-releases and post-release management

Between 2013 and 2018, captive-bred choughs were soft-released in small cohorts replicating normal family group size.

The plan was to release chicks shortly after fledging although sub-adults (< 4 years old) were used for the first release. Captive breeding at Jersey Zoo was not successful until 2014.

Cohorts acclimatized and socialized in the release aviary for a minimum of 2 weeks and trained to associate a whistle with food, enabling staff to call birds back to the aviary if needing re-capturing. Each cohort was initially given a set amount of time outside then called back in for food and confined until the next release. Duration outside increased day by day until reaching full liberty. Staff followed any bird that failed to return attempting to lure it back if feasible. If it had gone to roost, staff would return at sunrise to retry.

All birds were fitted with leg rings. Tail-mounted VHF transmitters were fitted to all birds released between 2013 and 2016. Initially, they received three supplemental feeds a day, as in captivity, reducing to once a day. This continues to the present day permitting close monitoring.

Jersey Zoo’s Veterinary Department conducted pre-and post-release faecal screening to monitor parasite levels, administer wormer if necessary, and have also treated physical injuries.

Enabling factors

- Dedicated staff willing to go above and beyond for the species.

- Supportive public with a means and willingness to report sightings away from the release site

- Jersey Zoo has its own veterinary department with expertise in avian medicine and experience of working with the species.

Lesson learned

- VHF tracking had limitations. GPS technology was not available for the species at the time. With regards to dispersal data, staff were often more reliant on public sightings than VHF tracking methods. However, VHF tracking was invaluable when locating missing individuals recently released. The team were able to locate birds and provide supplemental feed or on one occasion recover a dead bird allowing vets to carry out a post-mortem.

- Supplemental feeding should continue post-release to support the population during times of limited wild food availability. Survival rates were high during the release phase. Losses were attributed to starvation when the individual could not access supplemental feed.

- Greater success is achieved by releasing choughs under six months of age.

- Individuals reared alone without siblings are more likely to fail in the wild even if parent-reared in captivity.

- Adaptive management is key. Have a plan but be prepared to deviate in reaction to the species needs.

Management and protection of the wild breeding population

Captive reared birds tend to use the same type of nest in which they were raised. Based on this theory, nest boxes were installed along cliffs and a working quarry adjacent to the release site. Ronez, the quarry owners, paid for a UK expert to visit Jersey to help plan, design, and install the boxes.

The first nests, in 2015, were inside quarry buildings, not the boxes. Boxes began to be used as competition for nest sites increased. When two nests failed due to being built on dangerous machinery, staff installed boxes and successfully encouraged the pairs to nest in them, allowing quarry staff to continue operations.

Nesting activity is closely monitored allowing staff to estimate incubation, hatch, and fledge dates based on pair behavior at the supplemental feed and/or from direct nest observations. Chicks are ringed and DNA sexed in the nest where feasible. Alternatively, fledged chicks that visit the supplemental feed site can be trapped in the aviary when called for food, ringed, and immediately released. This option was used in 2020 and 2021 when COVID-19 prevented access to the quarry.

The recently revised Jersey wildlife law gives full protection to chough nests. Staff are now working to increase public awareness and offer nest boxes as mitigation when choughs nest on private property.

Enabling factors

- Bringing in outside expertise

- Developing a strong stakeholder relationship - Ronez appointed a liaison officer who works with Durrell to access, monitor, and protect nest sites.

- An enthusiastic team willing to go above and beyond for the species.

- Accessible nest sites with an alternative option for ringing juveniles/adults, i.e. the aviary at the supplemental feed site.

- A supportive public equipped with species knowledge, the means to report sightings, and are respectful of the wildlife laws.

Lesson learned

- Public awareness and support have resulted in additional invaluable data about dispersal, roost and nest-site selection, and habitat use. In 2021, a new roost site was discovered at an equestrian yard when the owner contacted the project officer questioning the presence of an ‘unusual crow’. A single female chough was identified roosting in the stables with a visiting pair attempting to nest nearby. Despite this, an evaluation of the reintroduction in 2019 identified an overall lack of public awareness. As the reintroduced population grows and new territories form away from the protected release site it will become increasingly important to have an informed and engaged public supporting the conservation management.

- Staffing has been very limited and restrictive. There is no dedicated marketing or educational outreach team. During the breeding season, monitoring multiple sites is only possible if there is a student placement assisting the project officer.

Evaluation, dissemination, and effective conservation management.

Release management techniques, data collection, and the need for intervention are continuously being assessed to facilitate effective adaptive management on a day-to-day basis.

Dissemination of methods and results is an important tool to communicate to donors, attract new funding or stakeholder support, and increase awareness at a national and international level.

Monthly reports to project partners are published online at www.BirdsOnTheEdge.org in a reader-friendly format that engages with the public. As a result, the project has received funding, attracted post-graduate research, helped network with international practitioners and inspired other organizations.

Work is currently underway to analyze existing data, identify data gaps, and carry out research that will aid the development of a long-term management plan.

Durrell recently incorporated the Open Standards for the Practice of Conservation into their strategic planning using Miradi software.

Enabling factors

- An existing organizational ethos to assess, plan, implement, evaluate, and disseminate projects.

- A supportive network of people with a wide variety of skills.

- Financial backing to set up, run, and develop online tools and resources.

Lesson learned

This building block is ongoing and hard to review at present.

Impacts

The red-billed chough is no longer locally extinct in Jersey. There is now a resident breeding population of ten pairs consisting of both captive-reared and wild-hatched birds. Conservation grazing was initiated in Jersey to ensure suitable foraging habitat is maintained for the choughs. Together these actions contribute to safeguarding the island’s biodiversity.

In 2020, a wild-hatched Jersey chough was discovered living in Normandy, France. Natural re-colonisation in Normandy and across the Channel Islands is now a feasible option potentially reconnecting the depleted French and British populations.

The success of the project has inspired other organisations to plan chough reintroductions in the UK (Kent and Isle of Wight) and potentially the Julian Alps, Slovenia. Both locations using the species to drive habitat restoration.

Local stakeholder engagement has enabled greater public awareness of Jersey’s conservation issues and knowledge of corvids, a group unfairly persecuted by islanders.

Capacity building through participation and teaching is a valuable resource. Jersey Zoo student placements regularly assist the reintroduction and post-release monitoring acquiring new skills such as radio-tracking and husbandry techniques.The Durrell Conservation Academy integrate the project into their curriculem including field trips for course participants and visting University groups.

Beneficiaries

Red-billed choughs

Associated coastal grassland bird species in Jersey

Jersey’s island biodiversity

Islanders

Tourists

Students

Story

Hand-rearing has played an important role in the reintroduction’s success. Eight of the forty-three choughs released were hand-reared. All eight survived for at least three years or more post-release and six went on to breed in the wild.

Jersey Zoo developed artificial incubation and hand-rearing techniques through a need to encourage double-clutching in captivity and to intervene when an egg or chick was compromised. Some critics questioned the suitability of hand-reared corvids for release due to their notoriety for imprinting.

Precautions were taken to avoid imprinting (feeding with a hand puppet, audio playback of chough calls in-between feeds and creche rearing). Chicks moved to an enclosure within the release aviary pre-fledge so that when they did fledge, they strongly associated the aviary as home. This makes it easier to manage the initial release phase. Whilst confined to the aviary they could safely observe and interact with the previously released cohort who returned for supplemental food and, in some cases, to roost. They then strongly associate the release aviary as home making it easier to manage their release.

In 2016, an imprinted female called Gianna was used to help foster rear four chicks for release. She effectively formed a pair bond with her keepers allowing them to co-parent the chicks as a sire and dam would in the wild. The chicks, hatched in an incubator, were hand-reared for the first five days then moved to a nest box in Gianna’s aviary. At four weeks of age, they moved to the release aviary where keepers continued to hand-feed.

Compared to fully hand-reared or parent-reared chicks, the fostered chicks took longer to integrate into the flock already living at liberty. They would stay near staff (<5 meters) when foraging outside of the aviary rather than with the main flock. Day by day keepers would move closer to the main flock to encourage the chicks to join. Eventually, one by one, they joined the flock and began roosting with them away from the aviary.

One chick has since reared three broods. Another became the first to establish a breeding territory away from the release site. Using hand-reared and/or foster-reared birds has clearly paid off. In addition, via monthly blogs and social media, their story has engaged stakeholders and the general public strengthening support for Birds On The Edge.