A Suitable Home for Antonio: A Community-Based Biocultural Corridor for Wild Felid Conservation in Private Reserves within the Serranía de los Paraguas KBA, Colombia

This project is developed on rural farms and Civil Society Natural Reserves within the KBA Serranía de los Paraguas, part of the Tropical Andes and Biogeographic Chocó biodiversity hotspots and the DRMI Serranía de los Paraguas protected area. Unsustainable livestock near forests safeguarding water sources has triggered human-wildlife conflicts (HWCs), tied to land-use change, biodiversity and ecosystem service loss, livestock predation, and retaliatory poaching. To address this, we propose a bottom-up approach involving landscape planning, adaptive livestock practices, sustainable energy for rural homes, behavior change toward wildlife, and community-based jaguar monitoring. This promotes long-term coexistence and improves life quality for people and jaguars, contributing to the Global Biodiversity Framework targets and Sustainable Development Goals, aligned with coexistence principles: do no harm, collaborate, understand context, integrate science and policy, and ensure sustainable pathways.

Context

Challenges addressed

Our solution focuses on the jaguar as a focal landscape species to address underlying HWCs ( level 2, IUCN), including gaps in adaptive planning and monitoring of public and private protected areas that supply water and support nearby productive systems (Targets 1, 4, 10, 14). It also addresses consequences such as forest conversion for production, agricultural expansion into preservation zones, wildlife hunting, and the introduction of domestic species into natural ecosystems (Targets 2, 3, 6, 10). This contributes to improving rural communities' quality of life by focusing on smallholder farmers whose lands ensure water supply but whose livelihoods are affected by HWCs (Targets 8, 11). The project also generates social and ecological baseline knowledge for governance and enhances access to electricity and clean water for rural families through the implementation of technological tools.

Location

Process

Summary of the process

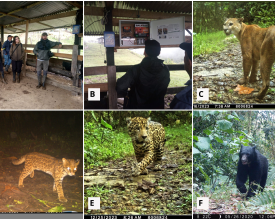

Our project’s motto is “Biocultural Corridor for Antonio,” highlighting the jaguar as a focal species to promote both biological (structural and functional) and cultural connectivity (adaptive farming, tolerance to negative interactions, and local recognition of the jaguar as an indicator of water sources). Developing a transdisciplinary plan for managing human–jaguar interactions at the DRMI Serranía de los Paraguas is key to integrating science, policy, and sustainable solutions. This plan will guide the logistics of the other components. Implementing community-based monitoring of jaguars and other mammals using camera traps will help identify priority areas for adaptive livestock management strategies, directly involving local farming families. These efforts will serve as key entry points to apply a behavioral change approach in strategic sites with jaguar presence. Farms where these strategies are implemented will serve as open classrooms for other producers and local educational actors.

Building Blocks

Development of a transdisciplinary plan for managing human–jaguar interactions at the regional scale in the DRMI Serranía de los Paraguas

Both the expansion of agricultural systems and the declaration of new public and private protected areas contribute to the intensification of HWCs. In this context, the development of regional plans that address territory-specific problems and contexts, and integrate all relevant stakeholders, will enable a preventive,comprehensive and sustainable management of human–jaguar interactions, improving quality of life for both people and jaguars

Enabling factors

- The stakeholders are willing to work together

- Protected areas management groups including comunity based, agrucultural, gender based, and government authorities at regional and local scale working together to make management plans

- Fund finding: The co management cometee works together to find financial and technical support to handle with HWI within protected areas

- Local initiatives with a bottom-up approach are prioritized over top-down initiatives that favor the interests of companies external to the territory.

Lesson learned

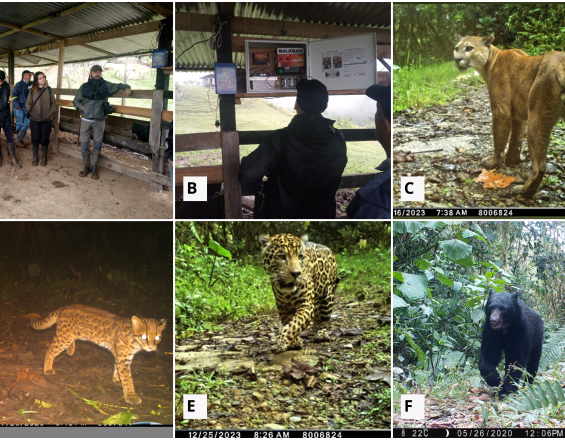

National funding sources have primarily supported top-down initiatives, with plans designed outside the territory by external groups. Through a bottom-up approach, an initial pathway has been developed to address level 1 HWCs, involving environmental authorities, agricultural extension units, and grassroots farmer organizations. This has facilitated the collection of reports on jaguar presence and attacks on domestic animals, enhancing our understanding of how jaguars use the territory. Between September and November, the group designed a pilot regional community-based monitoring of wild mammals using trap cameras (TC) within water resource conservation areas and private reserves, recording Antonio after two years since his last sighting. In 2025 (or 2026).

We aim to expand our planning to a more operational and administrative scale through the Plan4Coex approach, building on the positive partial results achieved so far.

Implementation of community-based monitoring of jaguars and ,mammal diversity using camera traps

We develop wildcats and potential prey community based monitoring with the families associated with Serraniagua in their private natural reserves by employing a small set of five trap cameras.

Enabling factors

Natural reserve land owners willingness to develop monitoring activities within their lands

Trap cameras availability, this is a limited resouce for our organization

Financial resources availability

Public Order

Favorable climatic conditions

Lesson learned

Through community-based biodiversity monitoring, many new, endemic, and/or endangered species of plants, amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals have been recorded, contributing to scientific knowledge and the implementation of technologies that support wildlife identification and habitat conservation.

A notable result of this effort is the documentation of six out of the seven felid species of Colombia within the area, including the rediscovery of the jaguar in the Andean region of Valle del Cauca, Colombia. Antonio, identified as an individual preying on livestock, has been tracked, revealing a movement route. We intend to explore this route as a landscape management strategy by implementing a robust trap camera monitoring program to identify potential anthropogenic impacts on wild mammals.

Applying a behavior change approach to address human dimensions related to jaguars in strategic areas where the species is present

According to IUCN guidelines for coexistence with wildlife, educational approaches are more effective when focused on promoting behavioral change towards wildlife. This can be achieved through well-designed processes targeting key stakeholder groups and addressing specific actions—such as the killing of jaguars or their potential prey, or the implementation of changes in production systems—within a defined time frame.

This approach is grounded in the Theory of Planned Behavior, which posits that human actions are influenced by intentions, which in turn are shaped by attitudes, subjective (or social) norms, and perceived behavioral control.

Our objective is to develop educational strategies for jaguar conservation that focus on these three key determinants of human behavior. In this way, we aim not only to ensure structural but also functional connectivity for the jaguar by promoting a culture of coexistence with other forms of life

Enabling factors

- Identification of key stakeholders

- Informed consent from the community

- Appropriate public order conditions to ensure participants' safety

Lesson learned

Most environmental education approaches developed in the territory to address human–wildlife conflicts (HWCs) have focused on providing information about the ecology of wild cats and promoting short-term deterrent methods. However, these activities have shown limited contribution to fostering long-term coexistence. In contrast, experiences that involve more in-depth processes—such as the active participation of local community in wildlife monitoring and the implementation of adaptive livestock management strategies on private reserves—have demonstrated positive effects on behavioral change, particularly among former hunters.

Resources

Implementation of adaptive livestock management strategies on farms adjacent to water source protection forests and public and private reserves

Due to their location near forests that protect water sources and public and private reserves, many agricultural productions are vulnerable to human-wildlife conflicts (HWCs). This vulnerability, combined with a lack or inadequacy of farm planning and the prevalence of outdated livestock management practices, puts at risk productivity in these mountain systems, biodiversity conservation, water resources, and associated ecosystem services

We include renewable energy technologies such us solar panels to power electic fences, improve livestoc water availability and sensored lights to mitigate economical loses in livestoc farms caused by predation over domestic animales, at the same time, we help rural farmer families to access electricity serveces and improve their food productivity, economicla and food founts

Enabling factors

Funding availability

Landowners willingness to include new technologies in their agricultural system

Adaptive livestock management strategies designed collaboratively with agricultural extension units, local small-scale farmers, and other professionals with relevant experience.

Lesson learned

The predation of domestic animals by wild predators has been addressed by local authorities and external foundations as a technical issue, through the implementation of “anti-predation strategies” such as electric fences, corrals, and other protective measures. However, these actions are rarely monitored for effectiveness or continuity and often end with the conclusion of contracts with private implementing entities. Our experience has shown that these measures are more effective when focused on improving farm productivity and the quality of life of small-scale farmers, based on the specific context of each property. Furthermore, monitoring and evaluation are more sustainable and efficient when carried out by local actors such as agricultural extension units, environmental authorities, and community-based organizations, increasing the likelihood of long-term success and continuity of these strategies.

We have implementing replicable technological strategies to mitigate economical losses by wild felids predation reaching a reduction of the 100% of attacks from cougar and jaguar over cattle in the Cerro El Inglés Communitary reserve, protecting vulnerable individuals by solar powered electric fences and motion-sensor lights and limiting the access of domestic animals to the forest by technifying water provision for livestock and solar powered electric fences. Having a demonstrative and replicable system used for education purposes with farmers from the region.

Impacts

By this solution we expect to establish key actions for coexistence with wild cats through a transdisciplinary plan adapted to the DRMI Serranía de los Paraguas. Advocate for its adoption as part of the DRMI management plan. Expand knowledge on jaguar ecology through scientific research. Assess mammal diversity and identify jaguar corridors near water sources and protected areas via baseline studies. Reduce threats to forests, biodiversity, and water by implementing adaptive livestock practices on at least 4 farms in El Cairo, Versalles, and El Dovio. Strengthen biological corridors through forest restoration in degraded areas and productive planning for conservation. Establish 4 sustainable, adaptive production models and sign 4 conservation agreements to protect riparian forests. Improve access to renewable energy for 4 farming families. Promote positive perceptions of jaguars among students from 3 nearby schools. Strengthen coordination with environmental authorities and local actors. Increase incomes from sustainable agroecological practices. Reinforce Serraniagua’s grassroots base through the project's results.

Beneficiaries

- Owners of Community-based Natural Reserves

- Owners of farms near water sources and public or private reserves

- Smallholder farmer associations

- Local educational institutions

- Environmental groups

- Regional co-management committee of the Serranía de los Paraguas

Additionally, explain the scalability potential of your Solution. Can it be replicated or expanded to other regions or ecosystem?

By developing a pilot landscape plan based on Antonio's movement route, we expect to provide a replicable, multidimensional regional conservation example for large predators in human-used landscapes, that may be applied to nearby conservation areas as the Tatamá Natural Park. In addition, through the integration of science and policy, we aim to influence local public policies that ensure the long-term financial sustainability of these processes, creating a replicable model for other regions of the country

Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF)

Sustainable Development Goals

Story

Local stories and old black and white pictures of hunted "tigers" (Panthera onca) where the only records of the presence of jaguars within the andean region of the department of the Valle del Cauca of Colombia, however, after establishing many prived protected areas, forest and water resources began to recover the landscape in El Cairo municipality. In recent years, the domestic animals of the guardabosques family in the RC Cerro El Inglés began to experience losses in their production animals, losing heifers, some of which simply disappeared, while others were found with signs of being attacked and consumed by a large wild predator. Thanks to the support of public and private organizations, a small set of seven camera traps was acquired to begin monitoring wild mammals. On one occasion, a dead colt was found near a water source with injuries on its neck and head. A camera trap was placed in front of the carcass, and to our surprise, there it was—a very large male jaguar with a distinctive A-shaped mark on its right cheek, defying all scientific predictions about the presence of the king of the American jungle in this region of the country. For us, it was both the most beautiful and problematic news: a jaguar in our territory... What message was it bringing us? How could we share this message with the community without causing adverse effects on the conservation of the species? After this wonderful encounter, we dedicated all our efforts to keeping track of Antonio by moving the few camera traps we had available in the reserves that showed signs of our emblematic male jaguar's presence. In 2022, we registered him again within the RNSC Cerro El Inglés, but lost track of him until 2024, when residents from the neighboring municipality of Versalles reported a dead colt with signs of jaguar consumption. Through collaborative efforts between public and private institutions, we registered Antonio once again in Versalles, sending a message of resilience and calling for the implementation of landscape planning and management methods that allow coexistence not only for Antonio but also for the other five wild cat species with local producers in their activity areas, addressing both social and ecological dimensions. We invite you all to come and be part of this ambitious project, which aims to combine technology, traditional knowledge, and scientific expertise to conserve one of the last individuals of this iconic species that is resisting extinction.