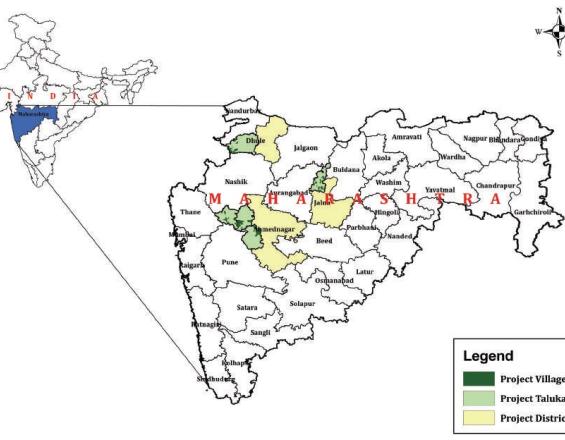

Water Stewardship Initiative (WSI) in semi arid regions of Rural Agrarian Maharashtra, India

With climate change events posing new threats to Water Ecosystem, Watershed Organization Trust (WOTR) realized that water management and agriculture production needed focus. Moreover, it was observed that the post-project period increased groundwater levels benefitted few who could dig open wells and bore wells. This led WOTR to initiate the Climate Change Adaptation project, having an important component- ‘Water Stewardship’ along with groundwater governance and climate-resilient agriculture overlaying Watershed Development. For establishment of an effective, efficient, and transparent governance mechanism, WOTR and WOTR’s Centre for Resilience Studies (W-CReS) launched the ‘Water Stewardship Initiative’ (WSI) and piloted it in 100 rain-fed villages of Maharashtra. The initiative helped to sensitize communities about the causes of their fragile ‘water health’ status, develop pedagogy to nudge them towards more efficient harvesting and use of water, and evolve a set of norms and regulations to manage water sustainably.

Context

Challenges addressed

Maharashtra state is facing repeated droughts over the years, resulting in crop failure and farmer suicides. All this is despite the extensive and successful water harvesting models implemented through watershed development projects. With groundwater has become the mainstay of survival and progress of farmers, there is drastic depletion of groundwater which has led to an increase in tanker dependency of numerous villages for drinking water and livestock needs. Although the Maharashtra Groundwater (development and management) Act is in place since 2014, there is an overall absence of local governance, particularly as groundwater is considered private property. Of particular concern is that, if groundwater management is not practised, land degradation will expand leading to poverty and loss of the natural resource base. Livelihoods are disturbed and outward migration increases in search of income. These issues need comprehensive ecosystem-based solutions to balance human and environmental development.

Location

Process

Summary of the process

The active community engagement in Water Stewardship starts with thorough understanding of Village water health chart that underlines the need for local water governance. In view of this, the Village Water Management Team (VWMT) is formed as village representation to take responsibilities to establish the governance. Water caretakers who monitor overall processes involved in WSI and look after if VWMT is taking efforts in right direction, provide guidance in technical as well as social components. VWMT and Water caretakers also conduct water budgeting seasonally for total planning of the resource. Depending on the outcome of the Water budget, water harvesting structures and water-saving techniques on farm level are designed and implemented. This has certainly incurred fruitful outcomes to achieve demand-side management.

Further the action plans, ShE workshops, continuous follow up, capacity building and training are key components to keep villagers in active participation and bring about personal behavioural and perception changes. The Maharashtra Groundwater Act, 2009 which is a very comprehensive state-level regulation finds its way of meaningful implementation in appropriate course through Water Stewardship.

Building Blocks

1. Village Water Health Chart

For understanding the local situation of quality and quantity of water resources, climate aspects and water needs in order to plan judicious and sustainable use of water, it is a key to gather all information. Therefore the Water Health Chart is prepared by the Water Caretakers and the Village Water Management Team (VWMT) in a cluster level event including participation of villages. The process involves answering key questions of the Water Health Chart, mostly common rural pattern of water resource management. Parameters like domestic water access including that of people living in hamlets, water needs for agriculture, water levels in dug wells and bore-wells during the year and many more reflect the ‘health status of water’ in a village. But it also includes social aspects with questions like “Is the education of girls affected by having to fetch water?”

The Water Health Chart makes a village community aware of the real situation of their water resources and water availability for their living and livelihoods. Thus, understanding the situation and problems related to water, triggers a ‘call to action’ to achieve prudent water management. The process also focuses on the behavioural change of users towards the adoption of appropriate water use practices.

Enabling factors

As villagers assess the parameters and rate their situation on the Water Health Chart, they better understand the difficulties of their daily life related to water scarcity and unavailability which they have gotten accustomed to. People become aware of how the water situation impacts their lives and livelihoods. Carrying out this exercise and displaying the chart in public has been very interesting component that immediately triggers the need for change. The use of the chart makes the community aware of and responsible for resolving the problems they face.

Lesson learned

So far, the Village Water Health Chart has been the foremost component of the WSI that shows immediate response of the villagers to the need of local water governance. Most of the project villages adopted the Village Water Health chart positively and took actions on each parameter of deteriorating status of water health. Almost 100 villages in 5 districts improved their water health within the first two years of the project through active participation in enhancing the water quality and quantity and by gaining support from WOTR, other practitioners, government bodies and schemes. The positive impacts were noted, but a few villages struggled to understand the chart completely considering the management of water resources at village level, the responsibility of local government and improvements in resource as privately accessible. This has led to confusion amongst villagers in initial phases of performing Village Water Health Chart. However, after in-depth discussions and repetitive execution of the exercise, villagers could sort their perceptions about their ownership and responsibilities towards water resources.

2. The Village Water Budget (WB)

The water budget focuses on central issues of environmentally sustainable and efficient management of available water. They are accepted by the local general body (Gram Sabha), the most important step in water governance.

The WB process has two steps:

1. The WB prepared in March / April calculates the water requirement for the whole year including that for the proposed Kharif (Monsoon), Rabi (winter) and summer crops. This exercise presents the water deficit which encourages the village to undertake repairs and maintenance of the water harvesting (WSD) structures earlier constructed, to meet the demand estimated in the water budget.

2. The water budget prepared in October (post monsoons) helps in planning for the Rabi season and to decide whether cultivating summer crops would be viable. This water budget calculates the total water available for use within the village for: (a) the water requirement is prioritized for domestic, livestock, and other livelihood needs after which the net water balance is considered available for agriculture. (b) Crops are selected and the area for their cultivation decided upon for the Rabi and summer seasons.

Enabling factors

General awareness programs and capacity building workshops create immense interest among villagers and Village Water Management Team (VWMT) members. Their willingness and active participation lead to various training programs and preparation of water budgets on regular basis. The water budget prepared in October (post monsoons) helps in planning for winter season and to decide whether cultivating summer crops would be viable. Such planning reduces stress of farmers regarding crop failure and irrigation requirements.

Lesson learned

While watershed development (WSD) may have been implemented to enhance the supply of water, it falls short of water management when the project is completed, unless the water budget is implemented. Since it has become mandatory by the Maharashtra Groundwater Act, the general framework of WB is accepted thoroughly by all project villages.

Villagers have started coming together more often to discuss water availability concerns. After facing economic losses from frequent dry spells and drought conditions, they obtained consensus on cultivation of low water requiring crops such as chickpea and sorghum instead of wheat and onion. Drinking and other domestic needs are given priority over irrigation water in view of possible water scarcity in the summers. Even in informal gatherings, villagers are confident and open to discussing alternatives to adopt efficient water use techniques.

3. Water Harvesting

Harvesting water through Watershed Development (WSD) is an important and widely accepted technique to increase the supply to meet the water requirements and make a village water secure. WSD is based on the principle of catching rainwater on ground surface; by constructing locale appropriate area treatments (Close Contour Trenches, Farm bunding, Tree plantation, Terracing, etc.) and drainage line structures (Gully plugs, Loose boulder structures, check dams, etc.), thus increasing the water stock on the surface and in aquifers. To implement water stewardship effectively, WSD plays a major role as it primarily strengthens supply side management. However, having implemented watershed treatments, regular repairs and maintenance are important to continue receiving the benefits.

Once the water budget of the village is calculated, the repair and maintenance requirement of water harvesting structures are documented. If village is water deficit, repairs and maintenance works are taken up in summer season for structures to function to their full potential. If the deficit is high and runs for longer period, new soil and water conservation structures are erected. All these works are done through Shramdaan (local contribution generally in kind) and convergence with the government and other donor projects if available.

Enabling factors

The recent drinking water scarcity due to erratic rainfall in most of the project villages motivated villagers to provide shramdaan and work to enhance the water storage potential. The convergence with government programmes during 2016 & 2017 has contributed to harvesting 8.62 billion liters in the project villages. Since convergence brought huge monetary contribution to the villages, it motivated villagers to take additional efforts and boosted their confidence to establish linkages with government projects to implement WSD activities.

Lesson learned

While WSD activities are always beneficial to improve the supply of surface and groundwater, with experience of more than 3 decades in the Watershed Development sector, some key points were learnt in the field. Appropriate water harvesting structures are constructed only as and where required, since it requires great human force and financial investments. Biophysical characters change with different geographies and hence WSD has been modified as per local needs. This considers water requirements by mankind by also securing water for local ecosystems and water base flow. While following the drainage line treatments, utmost care is taken to construct only minimum required structures so as to maintain flow for the downstream ecosystem and communities.

4. Stakeholder Engagement (ShE) Workshops

Management of surface and groundwater resources is a serious concern to local communities. Efforts at the individual or household level are not sufficient to plan and manage water. Hence it is essential that the diverse groups associated with a particular water resource come together to understand, plan and manage the resource judiciously, equitably and sustainably.

Watershed development, for example, through the Village Watershed/ Development Committee supported by the local governing body, brings all inhabitants of the entire village(s) together to regenerate their degraded watershed to enhance soil and water harvesting potential.

Two types of ShE events are:

1) Engaging the primary and secondary stakeholders at cluster level: these involve participation of direct water users and the neighbouring (upstream and downstream) communities to understand the scientific knowledge shared and active engagement in exercises.

2) Engaging representatives of the primary, secondary and tertiary stakeholders at block or district levels: These are mainly the government officials, experts in water, agriculture and allied sectors, practitioners, academics and research institutes. At this level of stakeholder engagement, participants discuss the larger perspectives of policy, advocacy and legal dynamics of water resources.

Enabling factors

Stakeholder Engagement workshops include group exercises, games and discussions. Open and healthy discussions are encouraged around common concerns. The scientific information regarding socio-economic, local biophysical and hydro-geological findings is shared by WOTR’s researchers to enable participants to make informed decisions. During the process, VWMTs and Water caretakers prepare water budgets followed by the water harvesting and water-saving plans. In all our workshops we promote women participation as a criterion for successful implementation.

Lesson learned

With more information and knowledge received through ShEs, the local stakeholders make informed decisions; immediate actions and development at the village level have taken place. Several water budgeting plans were made and followed through, which improved water sufficiency, provided drinking water security, and reduced crop losses. Introduction of villagers to water-saving and harvesting techniques improved water availability and water-use efficiency through the changed behavior of farmers. The rules and regulations made at the village level enhanced the power and reliability of local institutions in water management by increasing unity among the village community. However, adoption to new pathways and bringing about behavioral change is a very slow process. Villagers have insecurities of losing their ‘private’ share of water because of water budgeting. It is thus still anticipated to take a longer time to establish local water institution and informed communities to accept WSI completely.

Impacts

The village water health chart is a summary of water availability, its quality, types of uses and resource management set up, etc. which played an important role in mobilizing and motivating the community to design and implement interventions like water budgeting and water efficiency measures. The year 2018 was a drought year that posed serious water scarcity issues on local communities. However, 78 out of 100 project villages had water available within villages for domestic use in January 2019 due to planning and management through water budget. Repairs, maintenance and new constructions through volunteer work and convergence with government programmes during 2016 and 2017 have contributed to a total harvest of 61.44 billion litres in the project villages. The irrigation water demands were met using efficient micro-irrigation techniques resulting in saving 3.24 billion litres of water by 2000 farmers between October 2015 and March 2018. Total 78 project villages set rules for water use and crop management and have these rules ratified in their records of the local general body. The Stakeholder Engagement (ShE) events brought various stakeholders together on a common platform. These workshops provided them with an opportunity to deliberate and discuss ‘water’ as a ‘shared problem’. The activity also helped them to develop a common understanding of the ‘unseen’ sub-surface water i.e. an aquifer.

Beneficiaries

The main beneficiaries of this solution are rural agrarian communities (primary water users and neighbouring stakeholders that influence and/or are affected by primary users) of Maharashtra, particularly from semi-arid climatic regions.

Sustainable Development Goals

Story

The district of Jalna in Maharashtra state experiences dry and tropical climatic conditions. In the past 5 to 7 years, local communities faced severe droughts due to low and erratic rainfall with gradual temperature rise in the region. This climatic pressure has led communities to become more dependent on local groundwater systems which given the natural hydro-geological setting is very limited. Moreover, farmers switching from rain-fed to cash crops to increase their household income have resulted in the over-exploitation of groundwater. Irrigation water is given priority over domestic water requirements; also the access across various community classes or parts of villages (hamlets, settlements, etc) has become inequitable.

To address these social and behavioral challenges deliberately under WSI, intensive awareness programs and stakeholder engagement workshops were conducted. With rigorous thought sharing, scientific and traditional knowledge exchange, people started realizing the importance of a participatory approach and behavioral changes in order to sustain available water resources.

Participants shared that they now understand water as a common property and that everyone has a right over it; therefore water should be used judiciously. Mrs. Meera Shinde, from Lingewadi village, Jalna, describes how the situation has changed in her village -“Earlier, for fetching drinking water, no private well owners allowed others to draw water from their wells. After exposure and learning about this in stakeholder engagement workshops and discussions of the same within the village, some well owners allow others to take water from their private wells for domestic use.”

She further quotes “As water is needed for all, even for the animals and birds, we have made special water troughs for the animals in a remote hilly area where monkeys, wild boar and deer face difficulties in finding water in summer. They now frequently come and drink water from these troughs”.

The exercises of Water budgeting, Village Water Health chart and village level stakeholder engagement workshops indirectly helped more women like Mrs. Shinde who are now able to secure the water share for domestic need which has greatly reduced their stress for fetching water from long distance and rather have some additional personal and family time.