Locally-based mapping and management of resources in Kenya's northern drylands

Pastoralist communities do not simply ‘cope’ with arid and semi-arid conditions; rather they tailor their production strategies to harness the benefits that variability in rainfall and plant nutrients can offer, to maximize livestock productivity over other livelihoods. Recognizing this, this solution comprises two tools for facilitating bottom-up climate change resource management, in which decision-making and planning is placed in the hands of pastoralists at the ward level. Transferring management power

from the central government to the local level (also known as devolved power) increases capacity of communities to respond rapidly and flexibly in highly variable and sometimes unpredictable climatic conditions – something which is difficult to achieve when such power is centralized and top-down. This solution is published as part of the project Ecosystem-based Adaptation; strengthening the evidence and informing policy, coordinated by IIED, IUCN and UN Environment WCMC.

Contexto

Défis à relever

- Climate change in this already dynamic and unpredictable [area] is threatening local ecosystem resilience and service provision, through e.g. variations in rainfall, droughts, well-drying, increase livestock disease (including mortality rates of 40-60% during prolonged drought 2008-11)

- Governance, institutions and legal frameworks are weak, both for protecting ecosystems and for supporting pastoral livelihoods – over time the adaptive capacity of drylands communities has been eroded, as local voices have been excluded from natural resource planning and management, and possible policy involvment for pastoralist livelihoods has decreased

- Pastoralism is wrongly perceived as ‘backwards’ and a cause of environmental degradation, despite evidence suggesting otherwise

- There is a disconnect between community and formal planning systems, with the central government sometimes imposing planning uniformly, in a way which is not able to address or account for locally special conditions

Ubicación

Procesar

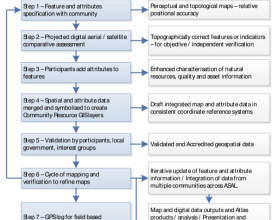

Summary of the process

The two building blocks are a community-led devolved climate change fund (Isiolo Community Climate Change Fund – CCCF) and a participatory mapping process. Participatory mapping has generated paper maps and GIS data layers depicting natural resource information; this data now supports strategizing and decision-making within the CCCF, facilitating spatially targeted, high-value and context-appropriate action. Both building blocks build capacity and foster community engagement, mutually supporting each other to empower communities and deliver devolved governance for climate change adaptation and building resilience. Importantly, both building blocks allow communities avoiding hard infrastructural strategies for climate-change adaptation by making a strong case for ecosystem-based adaptation.

Building Blocks

Isiolo County Climate Change Fund

Isiolo County Climate Change Fund (ICCCF) is a locally-managed (devolved) financial mechanism, allowing county and ward-level decision-making on investments for addressing climate change challenges. Piloted in Isiolo (2011-12) under the then Ministry of State for Development of Northern Kenya and Other Arid Lands, the mechanism was extended from 2013 to Garissa, Kitui, Makueni and Wajir counties and from 2018 is being scaled-out nation-wide by the National Drought Management Authority within the Ministry of Devolution and ASALs. Ward-level investments in Isiolo supported by the CCCFCinclude rehabilitation, fencing, sand damns, workshops, funding community radio and more.

Investment decision-making is participatory:

- WAPCs are formed through a public vetting process and consensus; male and female members are selected based on integrity, dedication, knowledge of the area and commitment to report back to the community.

- WAPCs identify priority investments which are submitted to the Isiolo County Planning Committee (CAPC) for review (the CAPC cannot veto proposals that meet jointly-agreed investment criteria).

- Once approved, investments are opened to competitive tenders. The successful provider receives payments in phases, based on certified completion of the previous phase.

Enabling factors

- Kenya’s new constitution mandates devolved (local, bottom-up) governance and climate change mainstreaming – core CCCF principles

- The engagement of the Climate Change Directorate, the Council of Governors, the National Environment Management Authority and the National Treasury in the scale-out of the CCCF mechanism are led by the National Drought Management Authority, which ensures the mechanism is being integrated into national and county-level planning

- Counties are setting aside between 1 and 2% from their development budget in support of CCCF

Lesson learned

- Communities drive planning and budgeting: through the Ward Climate Change Planning Committee (WCCPC) local Communities influence budgeting and ensure implementation of high-value, sustainable investments.

- CCCF anchored within and supportive of devolved (local) governance: The CCCF mechanism has led to the set-up of Ward Development Committees, and in existing CCCF pilot wards the WCCPC may be given the mandate to execute the development agenda at the county level; County Climate Change Planning Committees act as critical technical coordination units that ensure climate change activities are harmonized.

- Focus on public goods: public goods investments across the counties are delivering numerous economic benefits and have strengthened the local economies, supporting livelihoods or other important services.

- Inclusion: The CCCF is an inclusive mechanism, designed to include all social categories as well as technical experts, meaning critical planning structures are inclusive and investments are effective for all, including vulnerable groups like women and youth.

Resources

Participatory digital resource mapping

This building block builds on perception mapping, combining it with digital data and spatial tech to produce detailed and useful county and ward resource maps, documenting community knowledge of resources and attributes. The participatory mapping process allows traditional knowledge to enhance digital national-level data and vice versa.

Workshops introduced the project; Open Street maps satellite imagery was projected onto a wall alongside paper perception maps, and participants worked to transfer points of interest from the paper maps into GIS using coordinates to pinpoint locations in a way that could be verified and shared. Qualitative data on key resource points was then embedded into the spatial data. The maps were shared with participants and other stakeholders for feedback, before the process was repeated to refine.

Locally-grounded, scientifically-sound maps are useful in dryland contexts, where pastoralists must be able to utilize different resources at different times of year. Such maps also demonstrate– in a format understood by planners and others –where key resources are located, and how poorly planned/non-participatory development projects may restrict pastoralists’ access to resources.

Enabling factors

This building block was relevant to county planning processes and was an integral component of the CCCF mechanism. Being part of the CCCF mechanism meant that the process would have a tangible outcome, for example for guiding investments, and were available to other partners for technical support.

Lesson learned

Where necessary, e.g. when locations were covered by clouds in the satellite imagery, participants made quick ground-truthing visits by motorbike, using GPRS-enabled mobile devices to identify locations of important resources. Therefore, there is a need to make contingency plans for ground-truthing that would work in your context.

Identifying the appropiate scale is key; it isn’t always appropriate to stick to administrative boundaries when mapping, especially in pastoralists areas where administrative boundaries are frequently crossed to access resources. It’s important to think about which scale is suitable in your context.

Returning the maps to those who helped build them is critical, but technology could be a barrier. Leaving maps with communities usually means having to print them out.

Uptake and use of Open Maps was very quick, even among those with no prior experience of using digital technology – the 3D terrain model, which provided side-on views of familiar features was helpful here.

Impacts

Devolved (or locally-based) climate change planning allowed context-specific climate change adaptation activities to be planned, funded and implemented. This includes e.g. conservation of key water sources to prevent overgrazing, funding of local-led sustainable water resource governmence, operations and formal recognition of customary range-management institutions, and development (in collaboration with Kenya Meteorological Department) of a County Climate Information Services Plan for dissemination of climate-related information. Tangible adaptation and resilience benefits were experienced by an estimated 18,825 people from 2010-14. In 2014, Isiolo County managed to avoid reaching ‘alarm’ level of drought and its accompanying socioeconomic decline despite rainfall patterns that would be expected to bring this; this was attributed to good natural resource management. Devolved funding supported community-level planning through customary institutions and management for e.g. enforcement of grazing patterns and improved water governance, helping to avoid overgrazing. Overall, it was felt that land deterioration was slowed as a result of the devolved climate-change planning activities, and that resilience was improved as a result.

Beneficiaries

This solution benefits pastoralist communities in Isiolo and the neighbouring counties of Marsabit, Wajir and Garissa in particular