Financing Urban Park Management with Private Sector Participation

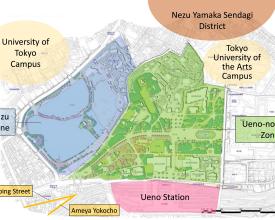

Ueno Park is one of the five oldest parks in Tokyo, first designated over 140 years ago. With about 12 million visitors annually, the park area is seen as the nation’s cultural and education center, containing seven museums, a zoo, a botanical garden, and several social facilities. When the sphere of Japan’s local autonomy was expanded in 2003, many local governments started to contract out park operation and management works to private companies with more than 90 parks managed by private contractors in Tokyo. Nevertheless, Ueno Park is directly operated by the Tokyo Metropolitan Government (TMG), due to their large-scale sites and diverse functions. Instead of contracting out, it adapts flexible legal settings and innovative collaboration with private sector. This solution explains how TMG manages Ueno Park in light of its historical background and meets current social needs for urban parks.

Contexte

Challenges addressed

In the 1990s, the public need for safe, clean and comfortable urban parks increased as an element of safe and livable cities, while problems such as deterioration of park management quality and aging park facilities were pointed out. Local governments responsible for management of urban parks struggled to find funding sources to manage the parks with its rapid growth and economic stagnation starting in early 1990. With a series of revisions to related laws and regulations encouraging private sector involvement in public service provision, many local governments started to contract out park operation and management works to private companies through competitive bidding process. Private-based park operation and management are expected to meet a wide range of public needs, provide better quality urban park services, and maintain public properties cost-efficiently.

Emplacement

Traiter

Summary of the process

Urban parks are increasingly expected to meet multiple social needs, such as increasing city amenities, disaster resilience, environmental conservation and restoration, international tourism promotion, local economic development, community improvement, and social cohesiveness. However, growing financial pressure is likely to make it difficult to sustain the quality of urban parks. Ueno Park directly managed by the local government called for flexible legal setting to meet its historical background and current social needs, and innovative endeavors to cost-effectively collaborate with private sector on urban park management.

Building Blocks

Flexible Legal Setting for Park Management

Ueno Park is flexibly managed to meet its historical background and current needs. To cover part of the expenses to manage urban parks, TMG allowed some private entities to run their businesses such as a restaurant and make a profit inside the park. While the Urban Park Act of 1956 prohibits any kind of private business activities in urban parks to avoid uncontrolled development, the government identified restaurants and small shops as part of the park facility that can be built, operated, and managed by private operators to meet public interest under government controls and allowed them to continue their commercial activities. This actions by TMG follows the Urban Park Act that allowed local governments to grant third party use or occupation of property, and construction and management of facilities. Consequently, several restaurants and small shops exist as park facilities in Ueno Park.

Enabling factors

- Proper balance of Government supervision and flexibility to enable private sector involvement

Lesson learned

In principle, public park management is not for profit-seeking activities, and uncontrolled private business practices may distort the original purpose of the public parks and exacerbate social inequity in urban contexts. The case of Ueno Park shows us that urban parks as public goods/services should be managed under government supervision in a proper manner but there also needs to be flexible and adaptive management in consideration of economic, social and cultural aspects of individual parks. Overly-strict operational regulations would diminish the diversity, attractiveness, and competitiveness of urban parks and limit the positive influence of park services on local communities and economies.

Creative Collaboration with Private Enterprises on Urban Park Management

For the creation of a new open space where people can get together, the local government coordinated open-air dining spots through a unique two-step management system allowed by the revised Local Autonomy Act. In the first step, the government built two one-story houses (Photo 1 and 2) to be used for cafes inside the park by special permission from the governor. Meanwhile, the government designated a public interest incorporated association as the permitted operator of the new buildings. In the second step, the association contracted out the café operation to two private companies selected from 15 applicants through a competitive bidding process. Selection criteria of the operating companies included consistency to the park’s basic revitalizing plan as well as profitability and quality of services to be provided to park visitors. Notably, with this two-step management a part of the profit from these two cafes can be efficiently reinvested to maintain and upgrade the park environment.

Enabling factors

- Designated Administrator System provided by the revised Local Autonomy Act of 2003

- Specifying an idea of dining spots in basic plans and obtaining a special permission for new profit-making activities in public park.

Lesson learned

Urban park management under public-private partnership schemes is obviously effective and more governments may adopt the scheme to meet the local needs to improve urban parks. However, merely contracting out park operation and maintenance services to private companies does not ensure desirable results for users. Local governments should develop plans and principles for urban park management with the participation of local stakeholders and experts, and the contracted private sector should follow the plans and principles. It is also important to manage urban parks with local specific and creative ideas along with the promotion of new private enterprises and business clusters in surrounding districts to maximize the local benefits.

Impacts

Economic Impact: This innovative public-private partnership system enables the local government to maintain the park assets more cost-efficiently and provide high-quality urban park services to a variety of visitors effectively. Improved park facilities and services, well-integrated with the surrounding environments and institutions including museums and universities, also significantly contribute to the local economy by attracting tourists.

Social Impact: The park contains many recreational and cultural spaces and contributes to improving both the mental and physical conditions of various age groups who can be refreshed and enjoy outdoor activities. The amenity setting also attracts diverse users and creates spontaneous interactions, which enhance social cohesiveness across urban communities. In addition, the park plays an important role in improving urban safety against potential disasters by functioning as evacuation sites and pathways for local residents.

Environmental Impact: The basic plan of the park revitalization includes rehabilitation of cherry blossoms and other green areas. The vast green spaces provided by the park are expected to reduce Tokyo’s heat island effect and to absorb greenhouse gas emissions from the urbanized areas. These spaces can also conserve indigenous species of plants and animals in central Tokyo.

Beneficiaries

- Residents in the vicinity of Ueno Park

- Visitors to Ueno Park and surrounding areas

- Private entities in Ueno Park and surrounding areas