Promotion de l'agrobiodiversité et de la restauration des berges dans le bassin fluvial binational de Sixaola

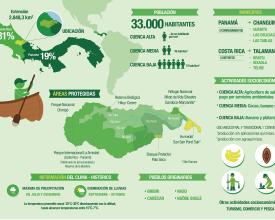

Les communautés du bassin de la rivière Sixaola (2 848 km2), partagé entre le Costa Rica et le Panama, sont métisses et indigènes, avec des taux élevés de pauvreté et de vulnérabilité. La région présente une incidence croissante d'événements climatiques extrêmes, en particulier des sécheresses, des températures élevées et des inondations, qui mettent en péril les moyens de subsistance locaux. Une solution globale est proposée pour accroître la résilience socio-environnementale. Elle consiste à combiner le dialogue, les capacités, les connaissances, les alliances et le travail de terrain pour promouvoir l'agrobiodiversité et reboiser le bassin. Avec les producteurs de 7 communautés, l'autonomisation locale et la coordination interinstitutionnelle, les mesures d'EbA sont mises en œuvre, leur impact sur la sécurité alimentaire est contrôlé et la coopération transfrontalière est facilitée. L'EbA est encouragée par des processus d'"apprentissage par l'action" visant à améliorer et à diversifier les pratiques de production, à sauver l'utilisation de semences autochtones et à restaurer les forêts riveraines par le biais d'actions binationales.

Contexte

Défis à relever

- La fragmentation de l'habitat, les fortes pluies et les mauvaises pratiques agricoles augmentent l'érosion des sols, la sédimentation et l'obstruction des voies d'eau, ce qui nuit aux moyens de subsistance locaux.

- Les menaces climatiques, telles que les sécheresses, les inondations et les pluies extrêmes qui réduisent la qualité de l'eau et affectent la production, sont en augmentation.

- Dans les bassins moyen et inférieur, la population dépend fortement de l'agriculture et est confrontée à l'insécurité alimentaire en raison des pertes de récoltes et de la dégradation des écosystèmes agricoles.

- La perte de la diversité génétique et des connaissances traditionnelles en matière d'agriculture avec des espèces indigènes suscite une inquiétude croissante.

- La région est très vulnérable sur le plan socio-économique et marginalisée (manque d'opportunités économiques et niveaux de pauvreté élevés).

- La capacité de gestion des municipalités et des gouvernements locaux indigènes est faible et nécessite une meilleure coordination intersectorielle et avec le gouvernement central.

Emplacement

Traiter

Résumé du processus

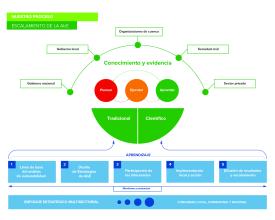

La solution intègre 3 blocs de construction (BB) : 1. apprentissage par l'action, 2. appropriation des mesures d'adaptation par la communauté et 3. La mise à l'échelle, afin d'améliorer la sécurité alimentaire et hydrique dans 7 communautés locales d'un bassin versant partagé. Le BB1 est transversal puisque le renforcement des capacités et l'échange d'expériences concernent et nourrissent tous les BB, en particulier lorsqu'ils sont entrepris par le biais d'une approche d'"apprentissage par la pratique". La mise en œuvre de mesures EbA au niveau des exploitations agricoles et des paysages forestiers (BB2) faisait partie de ce processus d'apprentissage et a permis d'accroître la résilience des écosystèmes locaux et des moyens de subsistance, en réalisant - des deux côtés de la frontière - des améliorations dans les forêts riveraines, la diversification de la production et la récupération des semences criollo (indigènes). Le projet BB2 a également permis de valoriser les connaissances traditionnelles et de promouvoir l'EbA à différents niveaux de gouvernance, en utilisant les expériences de terrain pour enrichir la gestion des bassins versants et justifier la mise à l'échelle de l'EbA (BB3). Ainsi, grâce à l'EbA et aux actions de gouvernance, il a été possible d'équilibrer les avantages immédiats pour les communautés afin de relever les défis quotidiens, avec une vision à l'échelle du bassin qui, à moyen/long terme, consolide le capital social et les capacités locales de prise de décision.

Blocs de construction

Apprentissage par l'action" et suivi pour accroître les capacités et les connaissances

En plus de former et d'aider les communautés à mettre en œuvre des mesures d'AEB par le biais de leurs pratiques productives, l'objectif est de produire des preuves des avantages de ces mesures et de créer les conditions nécessaires à leur durabilité et à leur extension.

- La vulnérabilité socio-environnementale de sept communautés du bassin de la rivière Sixaola est examinée afin d'identifier et de hiérarchiser les mesures d'atténuation des effets du changement climatique.

- Des diagnostics sont réalisés (productifs, socio-économiques et agro-écologiques) afin d'identifier les familles qui s'engagent à transformer leurs exploitations et de sélectionner celles qui ont le plus grand potentiel pour devenir des exploitations intégrales.

- Un soutien technique est apporté aux communautés, complété par des connaissances traditionnelles, afin de garantir que les mesures d'AEB contribuent à la sécurité alimentaire et hydrique.

- Des échanges et des formations sont organisés pour les producteurs (hommes et femmes), les autorités autochtones, les jeunes et les municipalités sur le changement climatique, la sécurité alimentaire, la gestion des ressources naturelles, les engrais organiques et la conservation des sols.

- Le suivi et l'évaluation sont effectués pour comprendre les avantages des mesures d'EbA et informer sur la mise à l'échelle horizontale et verticale.

- Les activités, telles que la foire de l'agrobiodiversité et les événements binationaux de reboisement, sont menées en collaboration avec les acteurs locaux.

Facteurs favorables

- Les années de travail de l'UICN et de l'ACBTC avec les communautés locales ont été un facteur clé pour garantir des processus de participation efficaces et inclusifs, atteindre un niveau élevé d'appropriation des mesures d'EbA et responsabiliser les parties prenantes (dans ce cas, les producteurs, les groupes communautaires, les municipalités et les ministères).

- L'accord binational entre le Costa Rica et le Panama (datant de 1979 et renouvelé en 1995) facilite le travail au niveau binational et la coordination intersectorielle, et approuve la Commission binationale pour Sixaola qui fonctionne depuis 2011.

Leçon apprise

- L'autodiagnostic des vulnérabilités face au changement climatique (dans ce cas, par le biais de la méthodologie CRiSTAL) est un outil puissant qui permet aux communautés de hiérarchiser ensemble les priorités les plus urgentes et les plus importantes et d'obtenir de plus grands bénéfices collectifs.

- L'application de l'approche de "l'apprentissage par l'action" au niveau communautaire permet de mieux comprendre les multiples concepts liés à l'EbA et de créer une communauté de pratique qui valorise et s'approprie les mesures d'adaptation.

- Il est important de reconnaître la complémentarité entre les connaissances scientifiques et traditionnelles pour la mise en œuvre des mesures d'EbA.

Ressources

Appropriation par la communauté des mesures d'adaptation basées sur les écosystèmes et la biodiversité

Les communautés se sont approprié les mesures d'EbA suivantes, une fois qu'elles ont été classées par ordre de priorité et mises en œuvre de manière participative dans le bassin :

- Restauration des forêts riveraines. Des manifestations binationales de reboisement sont organisées avec la participation des communautés locales et des écoles. Ces efforts réduisent l'érosion, atténuent le risque d'inondation et renforcent la coopération transfrontalière et l'autonomisation locale, notamment des jeunes. La durabilité de cette action est intégrée dans une stratégie de reboisement pour le bassin intermédiaire.

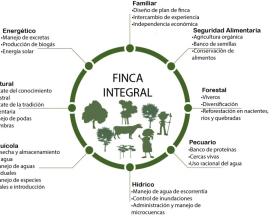

- Fermes intégrales / systèmes agroforestiers. Des pratiques sont intégrées pour gérer les services écosystémiques et générer une grande diversité de produits (agricoles, forestiers et énergétiques). Les pratiques de conservation des sols et la transition vers des systèmes agroforestiers avec une diversification des cultures et des arbres, des vergers tropicaux, des semis de céréales de base et des banques de protéines sont encouragées.

- Récupération et valorisation des semences et variétés autochtones. Des foires de l'agrobiodiversité sont organisées pour promouvoir la conservation de la diversité génétique( semencescriollo ) et de leurs connaissances traditionnelles. L'impact attribué à la foire est visible dans l'augmentation de la participation (exposants), de la diversité des espèces (> 220) et de l'offre de produits à valeur ajoutée.

Facteurs favorables

- La Foire de l'agrobiodiversité est née de la nécessité, identifiée par les communautés, de souligner l'importance de la diversité génétique pour les moyens de subsistance et l'adaptation au niveau local.

- Depuis sa première organisation en 2012, la Foire gagne en notoriété et se consolide avec l'implication d'un nombre croissant d'institutions (associations indigènes, municipalités, institutions gouvernementales telles que les ministères, les instituts de développement rural, d'apprentissage ou de recherche agricole, les universités et le CBCRS) ainsi que de visiteurs.

Leçon apprise

- La sagesse locale relative à la variabilité du climat et aux événements extrêmes provient des connaissances traditionnelles sur la résilience et l'adaptation, et constitue un ingrédient clé dans la mise en place de réponses communautaires au changement climatique.

- Le travail avec les familles a été un modèle efficace, tout comme la promotion de 9 fermes intégrales de démonstration (reproduites dans 31 nouvelles fermes). La ferme intégrale produit une grande diversité de produits (agricoles, forestiers et énergétiques) et optimise la gestion des ressources naturelles. S'il est encadré au niveau du paysage, ce modèle de production consolide l'approche EbA et facilite sa mise à l'échelle.

- La foire de l'agrobiodiversité s'est révélée être un espace précieux pour les producteurs ; ils peuvent y créer des contacts directs pour l'échange d'expériences, d'informations et de matériel génétique, ce qui explique le nombre croissant d'exposants provenant d'un nombre de plus en plus élevé de communautés.

- Le niveau d'engagement institutionnel observé dans les organisations impliquées donne de l'importance à la conservation et au sauvetage des semences indigènes et à leur relation avec l'adaptation.

Amplification et durabilité des mesures d'adaptation

La promotion des mesures d'EbA avec un niveau élevé d'implication communautaire et de liens binationaux a été un moyen efficace de parvenir à une plus grande interaction entre les acteurs communautaires, municipaux et nationaux, ainsi qu'entre pairs (réseau de producteurs résilients ; rencontre avec le gouvernement local). Les résultats sont, d'une part, une plus grande responsabilisation au niveau local et, d'autre part, l'extension des mesures d'EbA à la fois verticalement et horizontalement. Des contributions sont ainsi apportées à l'institutionnalisation de l'EbA et à la création des conditions de sa durabilité. La reproduction du modèle de ferme intégrale est le fruit d'un travail en réseau entre les producteurs, les communautés et les autorités locales, et d'un projet régional avec la Commission binationale du bassin de la rivière Sixaola (CBCRS), qui a fourni le financement. La foire de l'agrobiodiversité, le travail des producteurs en réseau et les événements binationaux de reboisement, qui sont désormais tous placés sous l'égide d'institutions locales et nationales, ont été d'importantes forces mobilisatrices du changement et des espaces d'échange et d'apprentissage. Sur le plan vertical, l'expansion de l'EbA a consisté à travailler avec le CBCRS pour intégrer l'EbA dans le plan stratégique de développement territorial transfrontalier (2017-2021) et avec le MINAE dans la politique nationale d'adaptation au changement climatique du Costa Rica.

Facteurs favorables

- Une grande partie du travail a été accomplie grâce au rôle de canalisation et d'orientation du CBCRS (créé en 2009) en tant que plateforme binationale pour la gouvernance et le dialogue, et de l'ACBTC en tant qu'association de développement local. Tous deux défendent les intérêts locaux et territoriaux et connaissent les lacunes et les besoins qui existent dans la région. Grâce à ce projet, ils ont pu relever les défis auxquels les communautés sont confrontées et améliorer la gouvernance dans le bassin, en promouvant une approche écosystémique et une large participation des acteurs.

Leçon apprise

- La coordination des efforts par le biais du CBCRS a montré qu'il est plus rentable de travailler avec les structures et les organes de gouvernance existants, dotés de pouvoirs et d'intérêts dans la bonne gestion des ressources naturelles et dans la représentation appropriée des acteurs clés, que de chercher à créer de nouveaux groupes ou comités pour traiter les questions liées à l'EbA.

- L'amélioration de la gouvernance à plusieurs niveaux et multisectorielle est un élément fondamental d'une adaptation efficace. À cet égard, il convient de souligner le rôle des gouvernements infranationaux (tels que les municipalités), qui ont un mandat de gestion du territoire, mais aussi des responsabilités dans la mise en œuvre des politiques et des programmes d'adaptation nationaux (par exemple, les CDN et les PAN).

- L'identification de porte-parole et de leaders (parmi les hommes, les femmes et les jeunes) est un facteur important pour encourager efficacement l'adoption et la mise à l'échelle de l'EbA.

Impacts

- Le système agricole intégral a été mis en œuvre, puis reproduit, afin d'accroître l'approvisionnement en nourriture, la formation des sols et la lutte contre l'érosion.

- Augmentation des capacités de : 40 agriculteurs qui mettent en œuvre des fermes intégrales et des systèmes agroforestiers, 20 jeunes formés au changement climatique qui mènent des projets dans leurs communautés, 3 municipalités et > 200 personnes formées à l'EbA, à la gouvernance pour l'adaptation et à la gestion de l'eau.

- Augmentation du dialogue, de l'échange, de la sensibilisation et de l'appréciation de la biodiversité grâce à la foire annuelle de l'agrobiodiversité (> 1 000 personnes) avec échange de semences indigènes entre > 100 agriculteurs depuis 2015.

- 7 500 arbres indigènes plantés dans le cadre d'événements annuels de reboisement binationaux pour restaurer les forêts riveraines.

- Preuve des avantages de l'EbA pour la sécurité alimentaire, en appliquant une méthodologie de suivi et d'évaluation dans 9 fermes intégrées.

- Renforcement du capital social, les communautés et les producteurs étant mieux organisés et informés.

- Engagements pris par des entités interinstitutionnelles pour assurer la durabilité des actions.

- L'élargissement des actions de l'EbA et des enseignements tirés à travers un réseau de producteurs résilients (40 fermes), la Commission binationale du bassin de la rivière Sixaola et les entités responsables des politiques sur le changement climatique à plusieurs niveaux de gouvernement.

Bénéficiaires

- 7 communautés (~400 personnes) comprenant des indigènes Bri Bri y Cabécar : Yorkín, Shuabb, Catarina, Paraíso (Costa Rica). El Guabo, Washout, Barranco (Panama).

- Commission binationale de Sixaola

- Municipalités de Talamanca et Changuinola (~33 000 hab.)

Objectifs de développement durable

Histoire

Les communautés indigènes et métisses du bassin de la rivière Sixaola dépendent fortement de l'agriculture de subsistance (céréales de base) et de la culture du cacao, de la banane et de la banane plantain. Cependant, la variabilité climatique affecte la production, en raison d'événements extrêmes, de l'incidence accrue des ravageurs et des maladies dans les cultures et des changements dans le débit de la rivière Sixaola. Pendant les périodes de sécheresse, le bassin moyen devient impraticable, ce qui entrave la commercialisation des produits, tandis qu'en cas de précipitations extrêmes, les quantités élevées de sédiments rendent la navigation dangereuse et diminuent la qualité de l'eau. Cette situation, combinée à de mauvaises pratiques agricoles, a rendu nécessaire l'introduction de mesures d'EbA dans les fermes et sur les berges des rivières afin de réduire l'érosion, de restaurer les forêts riveraines et de diversifier la production, augmentant ainsi la résilience des agro-écosystèmes et la sécurité alimentaire. Les communautés valorisent les connaissances traditionnelles et souhaitent promouvoir l'utilisation d'espèces indigènes, adaptées aux conditions locales, de sorte que toutes les mesures EbA mises en œuvre utilisent des espèces indigènes et/ou des semences autochtones.

Jeimy Carranza (BriBri) : "Dans le contexte du changement climatique, la question de la conservation des semences indigènes, des fermes intégrales et de l'agriculture familiale est très importante. Il s'agit d'un sujet dont l'impact positif sur l'environnement a été démontré depuis longtemps. ...... Les fermes intégrales et l'agriculture familiale sont des moyens de restaurer le paysage. Plus il y aura d'initiatives de ce type dans le bassin binational, plus les communautés seront en mesure de se rétablir ou de résister aux effets négatifs du changement climatique.

Milton Hernández (Yorkin) : "Je vois maintenant ce qui est vraiment important : cela m'a amené à changer personnellement. J'arrive maintenant à ma ferme, quelle beauté ! Je le vois moi-même. J'ai ceci, j'ai l'autre, j'ai l'autre, j'ai ? Avant, je n'avais pas cela. Et nous avons des terres pour faire une très bonne ferme. Maintenant, nous le voyons. Et j'en suis très heureux".

Miriam Morales (Yorkin): "Pour nous, la foire est très importante parce qu'elle nous permet de collecter des semences ; les semences viennent d'ici, de la région, et parfois nous ne cultivons pas et les semences se perdent, alors de cette façon nous pouvons sauver les semences perdues ? C'est une façon de partager avec d'autres producteurs, et de partager les semences, parce que c'est aussi dans notre culture. Lorsque nous avons des semences, nous les échangeons toujours... "