Associated Mangrove Aquaculture

Expanding shrimp aquaculture has driven mangrove loss worldwide, making tropical deltas and coastlines vulnerable to erosion, flooding and land-loss, thus reducing livelihood options for the coastal populations. In Demak district in Central Java, Indonesia, we introduced the Associated Mangrove Aquaculture (AMA) systems. Farmers were asked to give up part of their aquaculture pond by building a new dike with new gates while creating a sloped space for a riparian mangrove greenbelt. To create willingness and capacity, local shrimp farmers were trained on the job through Coastal Field Schools that promoted environmentally friendly aquaculture practices and could boost their income. In the first year, about 100 farmers in Demak converted about 10% of their total 104 ha of ponds into mangrove habitat, where sediments settle and mangroves recruit (regrow?) naturally within one year.

Context

Challenges addressed

The first challenge, farmers willingness to reduce pond size, was levied through the increased yields and incomes after the fieldschool training. The 2nd, enough capital for the building of the new dike and watergates, was relieved with a Bio-Rights subvention (see building block Bio-Rights). For the 3rd challenge, technical implementation, we prepared guidelines, held a training for the fieldworkers and conducted practical workshops for the participating farmers in each community. The 4th challenge relates to removing the old dike as this may lead to loss of landrights and to exposure of the bunds(?) of neighboring ponds. As a first step, farmers opened the water gates in the old dikes more frequently or permanently; when all ponds along a waterway are converted into Associated Mangrove Aquaculture Systems and the community has ruled on the property rights, farmers can stop maintaining the old dikes or remove them.

Location

Process

Summary of the process

The CFS created knowledge and awareness on the importance of mangrove, and built the capacity of farmers to sustainably increase their yields and income. Overall, this gave them the willingness to contribute to greenbelt recovery either by giving up entire ponds or building AMAs. The Bio-rights contracts provided these farmers a compensation either for the lost income, or for the investment in the extra dike with new water gates. The latter was organised, as traditionally, in groups who helped each other. [I don't understand this sentence. Is it necessary?]

Thus, these resource-poor farmers were given the human, social and financial capacity to transform their aquaculture production system and contribute to the recovery of the riparian greenbelts by making an AMA from their ponds. As fishermen benefit from improved catches, they support innovation at a community level; attribute budgeting for greenbelt recovery; and rule on property or user rights of mangrove products.

Building Blocks

Coastal Field Schools

Most aquaculture farmers in Indonesia achieve low yields or benefits due to insufficient training, poor practices and the use of chemicals and antibiotics that disturb the ecological balance. CFS is a learning process that builds the capacity of local small-scale pond farmers and trains small groups on good practices. During one production cycle (12-16 sessions), farmers learn pond ecology, pond management using low external input sustainable aquaculture (LEISA), and the ecology of coastal waters, including the functions of mangrove greenbelts (raising awareness for mangrove rehabilitation). Farmers study the agro-ecosystem, design aquaculture production systems, observe demonstration ponds, synthesize data, and debate with colleagues. They learn to make liquid and dry compost to cure, fertilise and manage the soil and water of their ponds. Finally, they make informed decisions on next steps of pond management. Through this process participants can determine the new practice(s) that are practical for them to apply straight away. Farmers also acquire more confidence in decision making and public speaking. In this project, after finishing the curricula, alumni continued to engage in post-field-school activities (such as on AMA and practicing forms of Integrated Multitrophic Shrimp Aquaculture (IMTA).

Enabling factors

- BwN Indonesia was the first project to show that disastrous coastal erosion can be reverted with permeable structures, which created trust.

- Resource persons supplemented the curriculum, which incited farmers to experiment further with new techniques and species.

- Pre-and post-testing enabled timely identification and adressing of problems

- A final meeting to identify follow-up activities resulted in the creation of independent platforms of farmers who continue to experiment and discuss their learnings.

Lesson learned

- In Demak, over 80% of the participants adopted LEISA to some extent; and these adopters tripled their gross margins compared to most of the non-adopters. This meant that the cost of the training was recovered within one year, making the CFS one of the most efficient rural training interventions. Moreover, the increased income encouraged efforts to restore mangroves for coastal safety.

- Some of those who didn’t adopt LEISA, were linked to other projects offering free seedlings of shrimp and milkfish on condition to follow project guidelines for aquaculture.

- Recruiting 50% women was a challenge. In its last year, the project’s female trainers recruited participants for two CFS that focused on women, including women among the early adopters as co-facilitators.

- After a CFS training, farmers continue to innovate, e.g., by fattening Blue swimming crab and becoming active in social (learning) networks. The CFS impacts both family and community livelihoods.

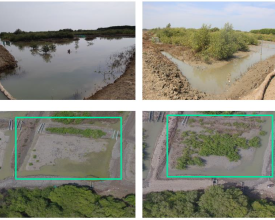

Associated Mangrove Aquaculture (AMA)

AMA connects aquaculture with mangrove greenbelts along shorelines in estuaries. Greenbelts are nonexistent in most farms. In contrast to most silvo-aquaculture systems where mangroves are planted on dykes and in ponds, in AMA they are located outside the pond, where magroves contribute to climate mitigation. Mangroves on dykes and in ponds hamper pond maintenance and their litter and shade reduce productivity. Leaves decompose in ponds, providing feed sources to shrimp and cultured organisms. However excessive litter increases ammonia levels, decreases dissolved oxygen content, and reduces pond productivity.

In AMA, the pond management is not hampered by leaves or shade, and benefits from an improved quality of inflowing water. A single farmer can practise AMA, but ideally all farmers along a canal improve the landscape. As farmers need to give up part of their pond area, which represents production potential, they are compensated with improvements in yield. Profits are obtained from the smaller pond, applying best practices from the Coastal Field Schools.

Enabling factors

- The CFS showed pond farmers how to increase their yields using LEISA and smaller ponds. AMA farmers were able to stabilise their income, despite extreme flooding.

- AMA provides farmers with additional income through forestry products and increased catches in their gate-traps, and higher fish catches.

- In Tanakeke Island (South Sulawesi), fish farmers that gave up all or a portion of their ponds for mangrove recovery could register for a tax break (Conservation Easement).

Lesson learned

- Farmers hesitated to remove the old dike bordering the waterway, as it limits their parcel. Leaving the old gates open most of the time was enough for a new sediment layer of 10 cm/year, and influx of seedlings for natural mangrove regrowth.

- The Bio-Rights financing mechanism and group collaboration are essential accompanying measures to recruit poor pond-farmers.

- When the pond dyke is under heavy protection or bears a large road, moving the dyke needs district planning and major investment.

- Pond dyke(s) carrying roads suitable for carts can be moved in unison by the neighbouring owners, even though this requires planning and incurs costs. Dykes with footpaths or bike roads can be moved more easily.

- Pond bunds that are shared with neighbours who are reluctant to change their system will need structural reinforcement, as the changing water level may cause erosion or uneven pressure.

- The remaining pond should have a width of 20m or more. Narrower ponds are costly to transform or become economically unviable. We advise complete transformation to the mangrove greenbelt.

Resources

Bio-Rights

Many of the rural poor are caught in a ‘poverty trap to meet short term livelihood needs and forced to unsustainably exploit the natural environment. The exploitation leads to increased vulnerability and further constrains their development opportunities. Therefore, to reconcile aquaculture productivity with mangrove conservation and restoration, we introduced the Bio-rights financial incentive mechanism in Demak. In return for active engagement in conservation and restoration measures, communities received financial and technical support to develop sustainable livelihoods. Bio-rights agreements are conditional: payments to communities are only completed after successful restoration. The approach covers part of the costs the farmers or the community face to change their current unsustainable practice (degrading the very mangrove greenbelt that they rely on for coastal safety) into long-term sustainable livelihood strategies. This motivates them to take a long-term interest in their conservation work as well. Some community groups set aside a portion of the capital in a group savings fund.

Enabling factors

- Community groups in 9 villages along the Demak coast were supported by Indonesian staff from the Building with Nature consortium who resided in Demak district throughout the project timeline.

- Local communities appointed individuals to participate in the programs.

- All community groups should be well organised and able to access, receive and manage government funds.

- The Bio-rights approach relies on capacity and awareness of community members; both were raised through Coastal Field Schools.

Lesson learned

- Previously, after conversion of mangrove into ponds, farmers didn't reflect on links between their livelihoods and the mangroves. They passively accepted floods and decreasing yields of aquaculture and fishery.

- After the CFS had raised awareness, creativity and willingness, the Bio-rights approach was the last push for communities to dedicate areas for greenbelt restoration.

- Funds made available to community groups in return for performing ‘ecosystem services’ to boost livelihoods, enabled through Bio-rights 'package deals'.

- To ensure sustainable finance for mangrove rehabilitation, part of the funds can be set aside into a group savings fund and/or used for profitable economic activities. In Demak, one village started a commercial mangrove walk; others bought machines to prepare the (liquid) compost for their ponds.

- By including policy and advocacy in the package deals, communities managed to get measures rooted in village development plans. As a result, communities already receive ad hoc or annual village and district government funds for various measures.

Impacts

Associated Mangrove Aquaculture (AMA) creates a habitat where mangroves can recruit naturally, thus restoring mangrove greenbelts along the waterways in the estuary. These riparian greenbelts contributed to the conservation of biodiversity, sedimentation and thus the protection of the adjoining ponds, and improves water quality. The restored mangrove landscape with good connectivity between coastal and riverine habitats enhanced capture fisheries. AMA is a type of silvo-aquaculture, but in contrast to the usual systems promoted in Indonesia, where the mangroves are planted on the dykes and in the pond, the mangroves in AMA are located outside the pond and thus have more ecosystem functions. Moreover, separating the mangroves from the pond allows better management of the water quality for the cultured species, and smaller ponds generally provide higher yields. Through good aquaculture practices, the productivity of the remaining pond and farmers' incomes were boosted (see Building Block Coastal Field Schools). The coastline protected by mangroves and the increased incomes helped communities to adapt to and mitigate the impacts of climate change.

Beneficiaries

Fish farmers along shoreline (stable yields), further away (protected ponds)

Fishermen (improved fish stocks)

Entire community: reduced risks (flood, erosion), biodiversity.

Local authorities: reduced risks, local economy boosted

Sustainable Development Goals

Story

AMA and IMTA changed family livelihoods

Since 2000, pak Abdul Kohar did not stock shrimp or milkfish in his 2 hectare pond. In the second month after stocking shrimp, most of these died; while some were lost during spring tides. So, he harvested the wild seafood that got trapped in his pond and in the gate traps at full moon. In 2017, the Building with Nature Indonesia project proposed to the village group to apply AMA in ponds adjacent to rivers. The location of his pond matched the criteria, and he built the extra dyke and gates using money from the Bio-rights mechanism. In 2018, he started emptying his gate traps daily. The results made him very happy, next to fish, such as mullet and white snapper, he caught tiger prawns (Penaeus monodon) and white shrimp (P. merguensis); the last two he hardly ever caught in the last years. This made Kohar think that his pond could be used again for cultivation.

Also, in 2017, UNDIP-FPIK-Aquaculture looked for farmers who would pilot IMTA. In this IMTA, shrimp, milkfish, seaweed, cockle and a cage with tilapia are combined to take advantage of all nutrients in the water. Pak Kohar tried to grow the tiger prawns, milkfish, blood clams and seaweed together. In the first cycle, the shrimp did not die; in the third month, he harvested 50 kg of tiger prawns and 500 kg of blood clams, of which he initially stocked 200 kg. In addition, the milkfish harvest, which used to be only 200 kg before 2000, reached 600 kg.

Pak Kohar also succeeded in cultivating seaweed, and in producing enough volume to interested factory buyers. Later, he proposed to several other farmers to add seaweed in their shrimp pond. This initial success encouraged Kohar to manage his pond more seriously. After preparing the pond, he added tilapia to his other crops. His second year was even more successful: His yields doubled for shrimp and milkfish, and tripled for blood clams. In addition, the daily catches in his traps increased both in volume and variation. He also caught blue swimming crabs, which have a high selling price.

This overall success gave Kohar the capital to improve his other pond. Kohar also applies AMA, IMTA, and his other learnings from the AFS. From the remaining money, he bought a new motorbike for the daily transport of his small family.