Creating direct incentives through ecotourism for protecting wildlife

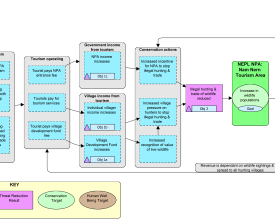

The Nam Nern Night Safari is a tour in Nam Et-Phou Louey NPA, Lao PDR, designed to give communities incentives to reduce illegal hunting and sale of endangered species. Tourism has been initiated as a measure to reduce threats in addition to enforcement and outreach activities. Incentives are created through a contract signed with the 1,186 families of 14 forest-edge communities, which ensures income to families for every tourist and wildlife sighting on the tour.

Context

Challenges addressed

Location

Process

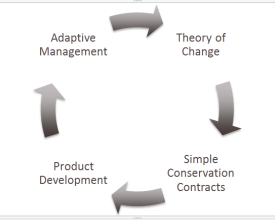

Summary of the process

Building Blocks

Creating a Theory of Change Model with Your Team

Enabling factors

Lesson learned

Creating Simple Conservation Contracts with Communities

Enabling factors

Lesson learned

Developing and promoting the tourism product

Enabling factors

Lesson learned

Revise Contracts with Community Input (Adaptive Management)

Enabling factors

Lesson learned

Impacts

There are three measures used for determining project impact. The first is the average number of wildlife sightings by tourists plus income earned by communities. If income to communities increases, wildlife sightings by tourists should also increase. In the first four years, income and wildlife sightings increased overall. However, increases in wildlife sightings alone do not indicate a positive impact, as more tourists along the river might only serve to scare hunters into other areas, with no actual reduction in threats. So, threats are also monitored. The ecotourism contracts create negative incentives for breaking protected area regulations through reductions in communal and individual benefits. As a result, the project was able to reduce hunting infractions from six to zero in the first four years. The project also compared total hunting signs (threats) between patrol sectors to determine the comparative advantage of a sector with tourism versus those sectors without. The project was able to demonstrate a flat-lining of threats in the tourism sector, in contrast to the average increases of threats found in non-tourism sectors