Creating sustainable tourism at the Samadai Dolphin House in Egypt

Spurred by the need of ensuring the sustainability of tourist visits in Samadai, the local government decided to deny access to the reef until a management plan was in place and enforced. Science-based management actions, including zoning and structuring of visits, were adopted on the basis of precaution, tourism was reorganised without eliminating it as a source of income, and the spinner dolphin resting habitat was maintained.

Context

Challenges addressed

Uncontrolled visits, including by swimmers, into the dolphins’ resting habitat had skyrocketed towards the end of 2003. Dolphins exhibited clear signs of discomfort, and there was a real risk that the dolphins might eventually abandon the area.

Location

Process

Summary of the process

The interaction amongst the building blocks was straightforward. The first demonstrated that Egypt was committed to protect marine charismatic species in its waters and went through the correct steps to address the issue. The second achieved the involvement of the stakeholder despite the authoritarian approach of the nation’s governance. In the end the effort was very successful and played to the advantage of both dolphins and the local economies, since it can be supposed that in the absence of management the dolphins might have abandoned their habitual resting area, which is expected to be a strong candidate for an Important Marine Mammal Area (IMMA) in the Red Sea region.

Building Blocks

Collaboration of authorities with international experts

Director of Egyptian Nature Conservation Sector, upon prompting by the tourist international community and local authorities, engaged to address the issue, seeking international expert advice. The decision was made to intervene and gather expertise; initial contacts and discussion with experts was expeditiously completed. Expert visits were organised, to facilitate the best possible understanding of underlying conditions and constraints to intervene and gather expertise; Initial contacts and discussion with experts is completed.

Enabling factors

Opportunity provided for meeting and discussions with IUCN expert at World Park Congress in Durban, South Africa, September 2003

Lesson learned

Expertise often cannot be found locally. International expert organisations such as IUCN can supply useful advice.

Stakeholders involvement through consultations and meetings

Gathering of specific local knowledge, issues, and circumstances; Reconnaissance trips made on site by experts, various meetings with local and national stakeholders (tourist operators, rangers, selected tourists, government officials), gathering of (scant) existing ecological and socioeconomic background information, understanding technical and logistic constraints to consider for visits.

Enabling factors

Government intervention and facilitation

Lesson learned

Local stakeholder contributions were often chaotic; information provided often unsubstantiated or contradictory, in attempts to protect personal interests. In situ investigations by experts are essential.

Expert management plan drafting, adoption, implementation

Enabling factors

Lesson learned

Impacts

- The establishment and correct management of the Samadai Dolphin House has demonstrated to locals that protected areas not only can coexist but also even enhance local economies; and

- A modest entry fee, impacting minimally on the tourist’s day-trip package cost, is accruing significantly to the budget of the region’s Red Sea Protectorates, paying also the stipends of rangers employed in adjacent protected areas.

Beneficiaries

- Spinner dolphins using Samadai as a resting area;

- locals gaining economic benefits and Red Sea Protectorates (economic revenues deriving from entry fees);

- tourists

Sustainable Development Goals

Story

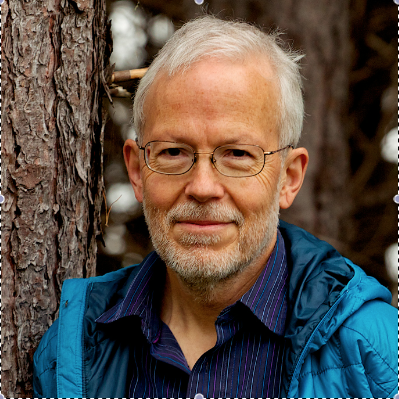

In Sept. 2003, at the Durban IUCN World Parks Congress, I was approached by Dr. Moustafa Fouda, head of Egypt Nature Conservation Service, asking for advice concerning the management of the Samadai Dolphin House. I expressed my availability to help. Three months later I was in Samadai, and could verify in person that a) the reef clearly contained spinner dolphin habitat that today would clearly be considered an Important Marine Mammal Area (IMMA) under more than one criteria; b) the reef was a beautiful, yet vulnerable, marine site where people could have close encounters with these dolphins; and c) the then Red Sea Governor was determined to do all that was possible to succeed. By the time I arrived, access to the reef had already been forbidden, and by being viewed by the local stakeholders as a conduit to a possible solution (and resumption of their business) my task was facilitated. My main problem was that no data existed: nothing on the extent of the dolphins’ use of the area (for example: how large would the minimal possible resting area have to be and how many swimmers’ visits could the dolphins tolerate? There were also few data on the swimmers. In the end a simple, provisional and precautionary management plan was drafted including zoning, setting upper limits for daily visitors and people in the water, and the use of a code of conduct. This was immediately adopted by the Governor, and in January 2004 Samadai was reopened to visits. In that same month I held a training course for the rangers, instructing them on how to collect minimal data on the dolphins’ and the tourists’ daily presence in the reef. Two years of such data allowed me to issue recommendations on how to improve management and change the management plan from provisional to final, but that never happened. Management could definitely improve today, although the original plan is still workable; however, Egyptian authorities have neglected to modify it on the basis of my recommendations. With such a good example of effective governance, the absence of a similar approach in the nearby locations of Fanous Reef near Hurghada, and Sattaya Reef near Hamata leaves me totally puzzled. Both of these areas are expected to qualify as candidate IMMAs, respectively, for resting Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphins and resting spinner dolphins, both heavily impacted by poor quality, irresponsible tourism (Giuseppe Notarbartolo di Sciara).