Crear un turismo sostenible en el delfinario de Samadai (Egipto)

Espoleado por la necesidad de garantizar la sostenibilidad de las visitas turísticas en Samadai, el gobierno local decidió denegar el acceso al arrecife hasta que se estableciera y aplicara un plan de gestión. Se adoptaron medidas de gestión basadas en la ciencia, como la zonificación y la estructuración de las visitas, sobre la base de la precaución, se reorganizó el turismo sin eliminarlo como fuente de ingresos y se mantuvo el hábitat de descanso del delfín tornillo.

Contexto

Défis à relever

Las visitas incontroladas, incluso de nadadores, al hábitat de descanso de los delfines se habían disparado hacia finales de 2003. Los delfines mostraban claros signos de incomodidad y existía un riesgo real de que acabaran abandonando la zona.

Ubicación

Procesar

Resumen del proceso

La interacción entre los elementos constitutivos era directa. El primero demostró que Egipto estaba comprometido con la protección de las especies carismáticas marinas en sus aguas y dio los pasos correctos para abordar la cuestión. El segundo logró la implicación de las partes interesadas a pesar del enfoque autoritario de la gobernanza del país. Al final, el esfuerzo tuvo mucho éxito y jugó a favor tanto de los delfines como de las economías locales, ya que se puede suponer que en ausencia de gestión los delfines podrían haber abandonado su zona de descanso habitual, que se espera que sea una fuerte candidata a Área Importante para los Mamíferos Marinos (IMMA) en la región del Mar Rojo.

Bloques de construcción

Colaboración de las autoridades con expertos internacionales

El Director del Sector Egipcio de Conservación de la Naturaleza, a instancias de la comunidad turística internacional y de las autoridades locales, se comprometió a abordar el problema, buscando el asesoramiento de expertos internacionales. Se tomó la decisión de intervenir y recabar asesoramiento; los contactos iniciales y las conversaciones con los expertos se completaron rápidamente. Se organizaron visitas de expertos para facilitar la mejor comprensión posible de las condiciones subyacentes y las limitaciones para intervenir y recabar asesoramiento.

Factores facilitadores

Oportunidad de reunirse y debatir con un experto de la UICN en el Congreso Mundial de Parques celebrado en Durban (Sudáfrica) en septiembre de 2003.

Lección aprendida

A menudo no es posible encontrar expertos a nivel local. Las organizaciones internacionales de expertos, como la UICN, pueden proporcionar asesoramiento útil.

Participación de las partes interesadas mediante consultas y reuniones

Recopilación de conocimientos, problemas y circunstancias locales específicos; viajes de reconocimiento realizados sobre el terreno por expertos, diversas reuniones con las partes interesadas locales y nacionales (operadores turísticos, guardas forestales, turistas seleccionados, funcionarios gubernamentales), recopilación de la (escasa) información de fondo ecológica y socioeconómica existente, comprensión de las limitaciones técnicas y logísticas a tener en cuenta para las visitas.

Factores facilitadores

Intervención gubernamental y facilitación

Lección aprendida

Las contribuciones de las partes interesadas locales fueron a menudo caóticas; la información facilitada, a menudo infundada o contradictoria, en intentos de proteger intereses personales. Es esencial que los expertos realicen investigaciones in situ.

Elaboración, adopción y aplicación de planes de gestión por expertos

Factores facilitadores

Lección aprendida

Impactos

- La creación y correcta gestión del delfinario de Samadai ha demostrado a la población local que las zonas protegidas no sólo pueden coexistir, sino que incluso mejoran las economías locales; y

- Una modesta cuota de entrada, que repercute mínimamente en el coste del paquete turístico de un día, está contribuyendo significativamente al presupuesto de los Protectorados del Mar Rojo de la región, pagando también los estipendios de los guardas empleados en las áreas protegidas adyacentes.

Beneficiarios

- Delfines tornillo utilizando Samadai como zona de descanso;

- beneficios económicos para la población local y los Protectorados del Mar Rojo (ingresos económicos derivados de las tasas de entrada);

- turistas

Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible

Historia

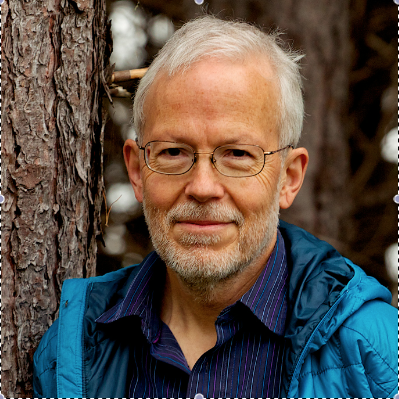

En septiembre de 2003, en el Congreso Mundial de Parques de la UICN celebrado en Durban, el Dr. Moustafa Fouda, jefe del Servicio de Conservación de la Naturaleza de Egipto, me pidió consejo sobre la gestión del delfinario de Samadai. Expresé mi disponibilidad para ayudar. Tres meses después estaba en Samadai, y pude comprobar en persona que a) el arrecife contenía claramente un hábitat de delfines tornillo que hoy se consideraría claramente una Zona Importante para los Mamíferos Marinos (IMMA) según más de un criterio; b) el arrecife era un sitio marino hermoso, aunque vulnerable, donde la gente podía tener encuentros cercanos con estos delfines; y c) el entonces Gobernador del Mar Rojo estaba decidido a hacer todo lo posible para tener éxito. Cuando llegué, el acceso al arrecife ya había sido prohibido, y al ser visto por los interesados locales como un conducto hacia una posible solución (y la reanudación de sus negocios) mi tarea se vio facilitada. Mi principal problema era que no existían datos: nada sobre el alcance del uso de la zona por parte de los delfines (por ejemplo: ¿cuál tendría que ser el tamaño mínimo posible de la zona de descanso y cuántas visitas de nadadores podrían tolerar los delfines? También había pocos datos sobre los nadadores. Al final se redactó un plan de gestión sencillo, provisional y cautelar que incluía la zonificación, el establecimiento de límites máximos de visitantes diarios y personas en el agua y el uso de un código de conducta. El Gobernador lo aprobó inmediatamente y en enero de 2004 Samadai volvió a abrirse a las visitas. Ese mismo mes impartí un curso de formación a los guardas, enseñándoles a recoger datos mínimos sobre la presencia diaria de delfines y turistas en el arrecife. Dos años de esos datos me permitieron emitir recomendaciones sobre cómo mejorar la gestión y cambiar el plan de gestión de provisional a definitivo, pero eso nunca ocurrió. Hoy en día, la gestión podría mejorar, aunque el plan original sigue siendo viable; sin embargo, las autoridades egipcias han omitido modificarlo basándose en mis recomendaciones. Con un ejemplo tan bueno de gestión eficaz, la ausencia de un enfoque similar en las localidades cercanas de Fanous Reef, cerca de Hurghada, y Sattaya Reef, cerca de Hamata, me deja totalmente perplejo. Se espera que ambas zonas sean candidatas a IMMA, respectivamente, para el descanso de los delfines mulares del Indopacífico y el descanso de los delfines tornillo, ambos muy afectados por un turismo irresponsable y de mala calidad (Giuseppe Notarbartolo di Sciara).