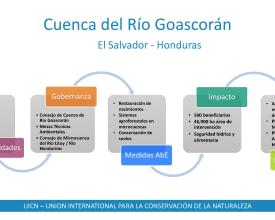

Governance for adaptation in the shared basin of the Goascorán River

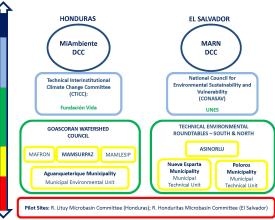

The lack of a border development agreement and the great diversity of actors are part of the governance challenges of the Goascorán River basin (2,345 km2), shared between Honduras and El Salvador. In order to adapt here to climate change, a governance model that is multidimensional (multilevel and multisectoral), participatory, flexible and ecosystemic is needed, one that integrates all basin stakeholders, periodically evaluates the adaptation strategies and measures implemented, and manages priority ecosystem services. In this solution, transboundary coordination was facilitated by establishing Environmental Technical Tables (El Salv.) and promoting their rapprochement to the Goascorán River Basin Council (Hond.). At a more local level, the Lituy River (Hond.) and Honduritas River (El Salv.) Micro-basin Councils were formed, creating capacities through a "learning by doing" approach. These experiences allowed adaptation actions to be up-scaled and strengthened the basin’s governance.

Context

Challenges addressed

- The basin’s binational nature implies collaboration and coordination challenges between Honduras and El Salvador, especially in the absence of a border development agreement that supports binational management.

- Only Honduras has a legal framework and a governance platform for the basin, although some structures have yet to be consolidated.

- There is little knowledge among decision makers about the multiple benefits of ecosystems for adaptation, which is reflected in municipal and national plans.

- There are degraded forests in water recharge zones and agricultural activities without soil conservation practices, which increase erosion and the tendency for migratory agriculture.

- There are climatic threats such as changes in rainfall patterns and rising average temperatures, which increase the risks of water scarcity and crops losses due to drought. Other threats include the poor solid waste management, contamination of water sources, and emigration.

Location

Process

Summary of the process

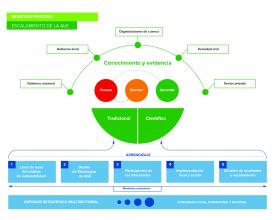

Governance for adaptation refers to the legal and policy frameworks, institutions, processes and mechanisms that allow power to be exercised, responsibilities to be distributed and decisions to be made, in order to respond to climate change. This solution is based on a governance model for adaptation that is multidimensional (BB1), participatory (BB2), flexible (BB3) and ecosystemic (BB4).

Adaptive governance in a transboundary context requires municipal and community management capacities (BB1 and 2) to be strengthened on both sides of the border, favouring local empowerment and inter-municipal and binational alliances. In this solution, multi-dimensional and participatory governance mechanisms were forged, incorporating more actors, creating new structures and adopting agreements and management instruments at various levels: micro-watershed, municipal, national and transboundary. In order to be flexible, these agreements and instruments must be subject to periodic reviews (BB3) in light of the results obtained and climatic variability. Additionally, results were achieved in the field following the implementation of EbA measures, which helped to consolidate adaptive governance using a basin ecosystem approach (BB4).

Building Blocks

Achieving multidimensional governance for adaptation

The work in Goascorán targeted several levels of decision-making to reinforce the basin’s governance through the vertical and horizontal articulation of socio-political platforms; all of this in order to achieve a multidimensional (multilevel and multisectoral) governance model for adaptation. At the community level, EbA measures were implemented in the field to improve food and water security. With municipalities, adaptation to climate change was incorporated into Environmental and Municipal Development Plans. At the micro-basin level, two Micro-basin Committees (one on each side of the border) were created as multi-stakeholder governance platforms, receiving training, preparing internal regulations and plans, and enabling wide-ranging advocacy (e.g. civil society, municipalities and municipal commonwealths). At the basin level, in El Salvador, where several Technical Tables operate, two Environmental Technical Tables were established for the north and south of La Union in order to articulate the basin’s shared management, and linkages were sought with the Goascorán River Basin Council that operates on the Honduran side. At the national level, the recent National Adaptation Plan of Honduras comprises the EbA approach, as does the new Regulation of the Honduran Climate Change Law

Enabling factors

- Honduras has a legal framework (Water Law) that creates the entities of Basin Councils and Micro-basin Committees, unlike El Salvador. With this, the Micro-basin Committee established in El Salvador, although very functional, lacks legal backing, which prevents it from managing projects and administering funds.

- Significant synergies were achieved with other projects in the Goascorán basin (e.g. BRIDGE and “Nuestra Cuenca Goascorán”), especially in coordinating actions to strengthen basin-wide governance and scaling up the EbA approach.

Lesson learned

- To strengthen governance at multiple levels, it is essential to initiate work with grassroots groups (community level) and with existing local governance platforms, such as, for example, Community Development Associations (El Salvador), to then scale-up to higher levels based on the experience acquired and the results achieved.

- The project known as BRIDGE left the following lesson learnt, which is also relevant here: "Water diplomacy does not necessarily follow a straight path. Effective strategies need to incorporate multiple dimensions and a phased approach, interconnecting existing structures and those under construction in the basin."

Achieving participatory governance for adaptation

The participation of all basin stakeholders has been at the core of the conformation and training of new governance structures for the Lituy (Honduras) and Honduritas (El Salvador) microbasins. The integration of grassroots (community-based) organizations, such as water boards, producer associations, women's or youth groups, Community Development Associations and educational centers, has been important. Locally, the leadership shown by teachers, women and community authorities contributed significantly to social mobilization and the adoption and scaling-up of EbA measures, making these actors an essential part of the "learning by doing" processes of communities. The result is self-motivated communities that participate and take on responsibilities. At the basin level, the Goascorán River Basin Council on the Honduran side was expanded, while in El Salvador, the most appropriate figure to accommodate the broad membership required was the Environmental Technical Table, which is why two Tables (for the northern and southern areas of La Union) were created and strengthened. Many of the members have become advocates for the work of the Tables with the aim to have these structures recognized by local authorities and legalized in the medium term.

Enabling factors

- Local actors are interested in coordinating actions and improving basin management, which contributes to making governance mechanisms and platforms effective and sustainable.

- MiAmbiente (Honduras) has the legal obligation to accompany the conformation of Micro-basin Committees across the country, and this must be preceded by a socio-ecological characterization that first allows each micro-basin to be delimited.

Lesson learned

- Having previous experience in carrying out participatory processes is an enabling factor for the successful conduction and conclusion of such processes (e.g. when prioritizing certain interventions).

- To have strategic alliances with different organizations is key, especially with municipality commonwealths (ASIGOLFO and ASINORLU), in order to promote spaces for dialogue and agreements regarding the waters shared between Honduras and El Salvador.

- The accompaniment of MARN (El Salvador) is necessary when addressing environmental issues and the adequate management of water resources, especially in a transboundary context. Once the negotiation with local actors had begun for the conformation of the Environmental Technical Tables, the support and participation of MARN’s Eastern Regional Office was important in order for these groups to be valued and regarded as governance platforms for the Honduritas River microbasin, in the absence of a formal institution for watershed management.

Achieving flexible governance for adaptation

Adaptation to climate change is immersed in a series of uncertainties regarding future climate impacts and development trajectories. Therefore, adaptation must proceed under a flexible “learning by doing" approach, integrating flexibility into legal and policy frameworks, and into sequential and iterative decisions that generate short-term strategies in view of the long-term uncertainties. In Goascorán, the lack of regulatory and policy frameworks for the management of shared basins limits the capacity to jointly respond to climate change - and therefore to be flexible and learn. This limitation was remedied by integrating adaptation into various management instruments at the micro-watershed, municipal and national level, and in transboundary agendas between local actors. The effectiveness of these (and other new) frameworks should be evaluated in interim periods, to allow for revisions and adjustments as knowledge about climate change increases; the same is true for EbA measures in the short term. The information that underpins these iterative processes must integrate Western science with local knowledge. In this way, it is possible to be flexible and identify new adaptation options and criteria for its evaluation.

Enabling factors

- A key aspect of governance for adaptation is the institutional and policy frameworks that back or facilitate it, and that confer it flexibility or not. In this sense, it was possible to take advantage of the window of opportunity offered by the updating of the Municipal Environmental Plans (El Salvador) and Municipal Development Plans (Honduras), the preparation of the National Adaptation Plan of Honduras, and the use of the legal figure of “Technical Tables” in El Salvador; all of which consecrate the value of governance for adaptation.

Lesson learned

- It is important to monitor and evaluate any improvements achieved through EbA, in order to use on-the-ground evidence to inform and substantiate changes to legal, policy and management frameworks, and in this way apply a flexible approach to adaptation governance.

Achieving ecosystemic governance for adaptation

Governance for adaptation requires an ecosystemic vision, whereby actions implemented in the field for building up the resilience of natural resources focus more on protecting watershed ecosystem services (forest-water-soil) and less on responding only to problems found at the level of individual farms. For this reason, the prioritization of restoration areas is key, since it must be with a view to improving water capture and also productivity (local livelihoods). The three types of EbA measures implemented in the Goascorán River basin were: 1) restoration of water sources, 2) soil conservation, and 3) agroforestry systems. This combination recognizes the interdependence of the forest-water-soil components and allows communities to witness positive changes over intermediate periods, which in turn increases their confidence in the "natural solutions" being introduced for water and food security. Territorial management with a basin or micro-basin vision also contributes to the ecosystem approach that is required for sustainable development, that is, one that is adaptive to climate change.

Enabling factors

- Climate change, and in particular, the availability of water for human consumption and agricultural use, are factors that concern most micro-watershed stakeholders, which increases their willingness to prioritize actions that favour water recharge zones and disaster risk reduction.

Lesson learned

- Once prioritized EbA measures were implemented, improvements in the conditions of the water recharge zones and in the organizational and governance capacity of the communities became evident, also helping to consolidate the concept that forest cover is a collective "insurance” in the face of climate change.

- The self-motivation of communities (around water and their livelihoods) and the leadership of key local actors are determining factors in achieving good governance for adaptation and in the successful implementation of EbA measures.

Impacts

- Creation and strengthening of the of the Lituy River (Honduras) and Honduritas River (El Salvador) Micro-basin Committees, with participatory processes for the definition of the internal regulations of these local governance structures.

- Adoption of the Action Plan of the Lituy River Micro-basin Committee.

- Implementation of ecosystem-based adaptation measures (EbA) with 10 communities in El Salvador and Honduras: 1) restoration of water sources, 2) soil conservation, and 3) agroforestry systems.

- Greater advocacy and management capacities of municipalities and their commonwealths, as well as knowledge concerning the advantages of EbA.

- Agreements between municipality commonwealths on both sides of the border, for improved ecosystem management.

- Greater water security for >5,000 families of the Lituy and Honduritas Micro-watersheds through the restoration of water springs.

- Incorporation of the EbA approach into: 7 Municipal Development Plans (Honduras) and the management capacities of 6 Municipal Environmental Units (El Salvador); the National Adaptation Plan of Honduras, which identifies EbA as a strategic axis and adaptive governance as a transversal axis; and in agreements between municipality commonwealths. This accounts for multidimensional scaling (vertical and horizontal) beginning with grassroots actors.

Beneficiaries

- Direct: >500 families from 10 communities of the Lituy (Honduras) and Honduritas (El Salvador) micro-basins

- Indirect: >5000 families from the Municipalities of Aguanqueterique (Honduras), Nueva Esparta and Poloros (El Salvador)

Sustainable Development Goals

Story

An important governance achievement of the AVE Project (Adaptation, Vulnerability and Ecosystems) was the conformation of the Lituy River Micro-basin Committee (Honduras) to meet the governance needs of this small micro-basin that is part of the Apane River micro-basin. Mr. Motzer Onan Acosta of the Conchas de Munuaque community and Deputy Secretary of the Micro-basin Committee, recounts his experience:

"Regarding the actions of the AVE Project in the Lituy River micro-watershed, I believe it was an opportunity for strengthening capacities in new topics that are essential for life as human beings. I am the youngest of the five members of the “Peasant Transcendence Group” and currently part of the Board of Directors of the Microbasin Committee. I have learned that ecosystems provide natural solutions to climate change, a clear example is the protection of the forest that somehow regulates temperature, provides oxygen which is life, and protects water springs in a natural way, which will provide us with more water quantity and quality. I also understand that the AVE project in the micro-basin was a learning process where success was seen reflected in the direct initiatives of families and the community in the execution of activities. As a member of the Microbasin Committee, I am aware that we must adhere to a work plan to take care of the natural resources present within the micro-watershed, with which we can have an impact at the municipal level, proposing joint actions for good governance."

The work with communities was a catalyst for actions at other levels. Thanks to local motivation and empowerment, both political advocacy goals (e.g. with municipalities) and escalation of the EbA approach were achieved. Likewise, a high level of participation was attained thanks to the mobilization power of certain leaders and community spokespersons. Mr. Rovell Guillén of Fundación Vida, AVE Project, comments:

"There are key players such as teachers in schools, who are figures who mobilize children and young people and facilitate meetings. Women have also played a highly active role, they get very involved and are listened to. This is evident in the reforestation campaigns where in the first activities, there were about 150 people. Also people from the lower part of the basin participated, who are supplied with water by the upstream areas being restored."