Governance for adaptation in the shared Sixaola River basin.

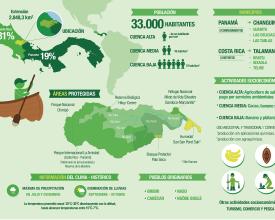

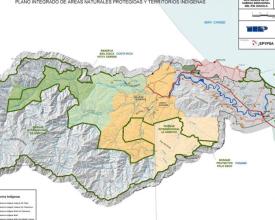

Sixaola binational river basin, shared by Costa Rica and Panama, flows into the Caribbean sea. The area has a high biodiversity and cultural richness with a mixed afro-descendant and indigenous population.

Communities face social vulnerability and lack adaptation capacities. The area is threathened by an increasing habitat fragmentation, changes in rainfall patterns and rising incidences of extreme weather events, particularly floods, all affecting local livelihoods.

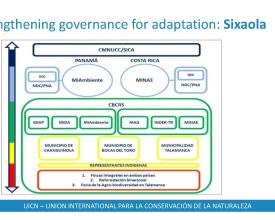

The solution aims to strengthen transboundary governance and improve institutional adaptation capacities. By working with the Binational Commission of the Sixaola River Basin (CBCRS), promoting public participation, while achieving greater binational cooperation and up-scaling solutions to basin scale.

A governance model was used that was multidimensional, participatory, flexible and ecosystemic, in order to foster adaptation actions that enhance local livelihoods and healthy ecosystems.

Context

Challenges addressed

- Due to climate change related impacts changes in rainfall patterns and seasons are expected, which would affect crop flowering and lead to increasing crop losses, occurrence of pests and diseases, and risk of floods.

- Sixaola River basin suffers from socio-environmental problems derived from unsustainable agricultural practices, degraded riparian ecosystems and its population’s high marginalization and poverty levels.

- Lack of knowledge among local actors about EbA benefits

- Although there is Binational Commission for the Sixaola River Basin (CBCRS), bringing together national and municipal government actors and various sectors from both countries, its management was weakened by lack of a binational territorial planning tool. Tool would allow to articulate efforts on both sides of the border. Its main governance challenge was to improve multi-level and multi-sectoral coordination, in order to work with a basin-wide territorial approach and clear priorities.

Location

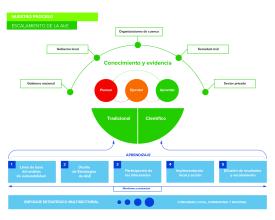

Process

Summary of the process

At the local level an EbA plan is designed. This is the vehicle for up-scaling results and discuss lessons learnt within the Binational Sixaola Comission. This solution promotes a governance for adaptation model that uses an ecosystem approach (BB1), is multidimensional (BB2), and participatory (BB3).

- BB1. Implement EbA measures with farmers to diversify agricultural production with the use of agrobiodiversity and watershed restoration actions.

- BB2. Binational cooperation has been strengthened through the implementation of binational activities of shared governance of water resources and EbA measures. The binational cooperation facilitated the implementation of joint actions and learning, such as: binational reforestation days, binational efforts to promote agrobiodiversity and risk management, etc.

- BB3. Stakeholder participation has been motivated at various levels (community, municipal and national), including groups traditionally marginalized from the watershed’s management. Municipalities have been involved in EbA actions seeeking for sustainability and ownership.

Building Blocks

The ecosystem approach into practice

Under an ecosystem approach, efforts seek to improve the livelihoods and resilience of ecosystems in order to reduce the vulnerability of local communities to the challenges of erratic rains, changing pf seasons, storms and consequent loss of crops. The EbA measures promoted are:

- Restoration of riverbank forests to prevent river bank erosion during extreme storms and flash floods. This is promoted with annual Binational Reforestation Days and guided by a Restoration Opportunities study in river banks.

- Agrodiversification was undertaken with local farmers to increase the number and varieties of crop species, fruit and wood trees in their plots, while combining with animals. This aim to improve the resilience of the system against erratic rainfall and changing seasonal patterns. The model is locally named as "integral farms".

- Learning and exchange through a network of resilient farmers with knowledge on EbA.

- Organization of agrobiodiversity fairs for the promotion and rescue of endemic seeds.

The model used a "learning by doing" approach and the adoption of iterative decisions that identify short-term strategies in light of long-term uncertainties. Learning and evaluation allows new information to be considered and inform policies at different levels.

Enabling factors

- Climate change and, in particular, changes in rainfall patterns, are factors that concern many basin stakeholders, which increases their willingness to prioritize actions that favour water and food security. As a result, many farmers agreed to incorporate sustainable agricultural practices in their farms, taking full ownership of them.

- The integral farms model facilitates understanding of the value of ecosystem services and helps to substantiate governance with an ecosystem approach.

Lesson learned

- When promoting dialogues on EbA, traditional and indigenous knowledge and experiences concerning climate variability and natural resources must be taken into account. This not only favours coherency in the selection of EbA measures, but also allows elements to be captured that can inform the actions of agricultural extension agencies in the basin and enrich national and regional policies.

- Indigenous knowledge is fundamental when it comes to knowing which seeds and crop varieties are best adapted to the socio-ecological context. Organization of agrobiodiversity fairs for the exchange and preservation of endemic species seeds intended to enhance the planting of native species. Some are more resilient against climate related stressors; a diverse farm enable and agro-ecosystems turns into protecting communities from negative impacts of climate change, providing food security.

- The reforestation events proved to be highly valuable activities. This type of action leaves an indelible mark on children and youth, and motivates them to replicate the activity in the future.

Achieving multidimensional governance for adaptation

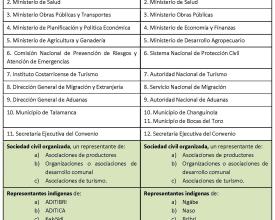

The Binational Commission of the Sixaola River Basin (CBCRS) functioned as a multidimensional (multisectoral and multilevel) governance platform for the basin. The CBCRS brings together representatives from different levels of government and sectors (including indigenous peoples and the local private sector of both countries) but needed to attain more effective vertical and horizontal integration. The preparation of the Strategic Plan for Transboundary Territorial Development (2017-2021) had the effect of fostering inter-institutional and inter-sectoral coordination and cooperation, forging dialogues on national frameworks and local needs, and promoting EbA.

At the local level Eba measures such as agricultural diversification with integral farms and reforestation actions were implemented. The aim was beyond individual impacts, to scale up lessons to the basin scale, such as:

- the CBCRS´s project portfolio

- the coordination of binational activities, such as Agrobiodiversity Fairs.

- the Biological Corridor Association of producers, which facilitated the exchange of experiences and peer-to-peer contacts (producers, municipalities)

Enabling factors

- The prior existence of the CBCRS (since 2009), covered under the Cooperation Agreement for Border Development between Costa Rica and Panama, was a key enabling factor, since the purpose of this binational structure (achieving greater transboundary coordination and leadership for good governance and the integral development of the basin) was fully consistent with the objective of improving adaptation capacities to climate change impacts in the basin.

Lesson learned

- Multidimensional governance is a central part of adaptive capacity. It is based on vertical integration of different stakeholders (local, subnational, national, regional), through the creation and/or strengthening of institutions where entities of multiple levels participate. It is combined with horizontal integration of sectoral authorities (public, private, civil society) in order to reduce isolated approaches in management and decision making, and allow mutual benefits and synergies between sectors and their adaptation needs to be identified.

- In adaptation, inclusion of municipalities is vital, since they have a mandate in territorial management, but also responsibilities in the implementation of national adaptation policies and programs (e.g. NDCs, NAPs).

- Peer exchanges (such as meetings between local governments) are an effective mean to awaken interest in the "natural solutions" offered by ecosystems.

- The articulation of project efforts across a territory is fundamental (e.g. between AVE and BRIDGE in Sixaola) in order to achieve greater impact through a coordinated work agenda.

Resources

Achieving participatory governance for adaptation

The Binational Commission for the Sixaola River Basin (CBCRS) needed to diversify participation in the basin’s governance. Although it brought together actors from different sectors and levels of government (national and municipal), some actors were still missing (such as the Municipality of Bocas del Toro, Panama, which joined in 2016). The CBCRS management was not yet consolidated, because of its complex composition and that it had neither a binational territorial planning tool with which to articulate efforts on both sides of the border, nor its own budget. Through an extensive participatory process, the CBCRS drafted a Strategic Plan for Transboundary Territorial Development (2017-2021) and expanded its project portfolio. Encouraging participation in this process, and in bi-national activities, has created conditions for civil society and municipalities to take an active role in the implementation of the plan and adaptation actions. Providing a space particularly for women, youth and indigenous people, usually marginalized of decision making. CBCRS plan also urged greater equality in the access to and use of natural resources on which local communities depend, thus favouring those groups most vulnerable to climate change and creating a sense of ownership.

Enabling factors

- Communities are willing to participate in dialogue, learning, search for solutions and joint actions. Most stakeholders in the basin are concerned and affected by climate change excessive rainfall that causes flooding.

- In order to achieve a broad participation, the integrating role of the CBCRS as a binational governance and dialogue platform, and of the (Talamanca-Caribe Biological COrridor Assotiation) ACBTC as a local development association, was indispensable.

Lesson learned

- In governance for adaptation, effective participation can enrich planning and decision-making processes, leading to results that are accepted by all parties involved

- Coordination between projects, and initiatives such as the Central American Strategy for Rural Territorial Development (ECADERT) that provided funding for the first project awarded to the CBCRS, contribute to the up-scaling and sustainability of the actions.

- Social participation and strengthening of organizational capacity, through the identification of spokespersons and leaders (amongst youth, women and men) is an important factor for the consolidation of these processes and, with it, governance structures.

- Encouraging public participation increases dialogue and the assessment and incorporation of knowledge (technical and traditional), as well as the inclusion of lessons learned from each sector.

- Future efforts should consider how to strengthen the incorporation of the agri-business sector (e.g. banana or cacao) into the governance for adaptation agenda.

Impacts

Strengthening of CBCRS representation through:

- Integration and awareness of involved communities, farmers, public institutions and civil society organizations.

- Integration of new actors (e.g. Municipality of Bocas del Toro, Panama)

Improved management, advocacy and coordination capacities of CBCRS through:

- Adoption of the Strategic Plan for Transboundary Territorial Development (2017-2021), as a key multidimensional governance achievement.

- Enhanced binational learning and cooperation (e.g. through the organization of joint activities, such as the Agrobiodiversity Fair and binational reforestation events).

- Synergies with alike projects and initiatives: IUCN BRIDGE project on transboundary water resource governance; Rural Development Central American Strategy (ECADERT).

Scaling up and mobilizing funds for EbA:

- Promoting EbA measures, such agro diversification through a resilient farmers network (> 40 farms).

- Close coordination with Ministries of Agriculture and agricultural agencies of both countries, and dialogues informed by learning about EbA for its integration into public policies

- Commitments to EbA and "Nature-based Solutions" by municipalities of both countries and Bribri Indigenous Peoples Development Association, upon signing the Declaration of Local Governments on Climate Change.

Beneficiaries

- Binational Commission for the Sixaola River Basin (CBCRS)

- Communities (~400 people): farmers, indigenous representatives (Bribri, Cabécar, Naso and Gnäbe), youth, women and educators

- Municipalities of Talamanca and Changuinola (~33,000 inhab.)

Sustainable Development Goals

Story

pMr. Juan Carlos Barrantes, Director of the ACBTC:

One of the most important contributions of the AVE Project was the strengthening of governance structures. Facilitating the undertaking of the CBCRS’s assemblies helped to develop instruments, such as the Rules of Procedure that sets the work of the CBCRS with a shared vision of sustainable development.

In addition, there were training processes in topics such as shared waters and environmental law, in particular, the diploma course in water governance and climate change with a basin approach, which was done using a virtual platform and was taken advantage of by several members of the CBCRS. Being in a process of constant learning has benefited the CBCRS.

Being constant was important in the operational process that led to the design of the Strategic Plan (2017-2021), as was combing support from other projects in order to produce a portfolio of projects that underpins the territorial investment plan.

During this time, there has been a greater appropriation by CBCRS stakeholders of the decision-making space that this platform offers and of its operational processes. This strengthens binational action, which is the result of greater coordination and collaboration between the two countries. This is having positive effects on the CBCRS’s financial management too, since it has facilitated access to new funding, including broader issues (eg. public health) and not only environmental ones.

On the other hand, there were specific actions in the agricultural arena, carried out in integral farms and through the organization of the Agrobiodiversity Fair. Bringing together farmers from the basin, and from either side of the border, has permitted a unified discussion on sustainable development actions and the search for environmentally-friendly production measures. The commission that organizes the Fair also includes public institutions from both countries, so these actors are also part of the discussion.

In 2016, the Municipality of Bocas del Toro (Panama) joined the CBCRS, which marked a milestone. In 2018, the Governor attended the Fair, and together with Panamanian producers, made the commitment to hold a similar fair in Panama. With all of the Governor’s convening power, two months later the first agrobiodiversity fair was taking place in Bocas del Toro. This demonstrates how far the collaboration between Costa Rica and Panama can reach, thanks to the work of the CBCRS and the organization of locally-driven activities