Identification of visions for protected area management and quantification of their consequences in Utrechtse Heuvelrug and Kromme Rijn (Netherlands)

The Kromme Rijn area is a dynamic cultural landscape, shaped by multiple uses and different elements of typical Dutch landscapes. Utrechtse Heuvelrug National Park within this landscape includes important forest areas and biodiversity values, but is also of historical and recreational significance. The region needs to be multifunctional given the dense population and many expectations towards the landscape, but different use interests are not always compatible.

In order to develop new solutions, identify new directions for policy and help society move towards synergetic options, an „inclusive conservation“ approach is being applied. As a first step, different visions for the use and development of the landscape have been identified through stakeholder interviews. These will provide the basis for modelling the consequences of these different stakeholder vision. Finally, stakeholders will discuss the visions and their consequences, deciding on a joint vision and pathways towards it.

Context

Challenges addressed

The Utrechtse Heuvelrug National Park and Kromme Rijn region is a peri-urban landscape, where a national park as well as several small nature areas are lodged in the mosaic of farms, small towns and other land uses. The region needs to be multifunctional given the dense population and many expectations towards the landscape, but different use interests are not always compatible. Thus, the main challenge for nature conservation and governance of the larger landscape those nature areas are located in is about re-conciling multiple demands in a resource scarce place. Multi-functionality is the norm and expected by stakeholders, but does not deliver in terms of individual functions. Among identified issues are declining biodiversity, over-crowding of recreation (especially in times of COVID-19 pandemic), tensions between agriculture and nature (for example, nitrogen fertilizers negatively affecting nature areas) etc.

Location

Process

Summary of the process

Together the building blocks present a combination of methods which allows to identify and investigate visions for development of protected areas and landscapes around them from the perspective of different stakeholders and dimensions. In this project we aim to collect perspectives beyond the traditional stakeholder groups (such as farmers, decision-makers) and focus on least studied group – local residents. We also disregard the assumption that they share the same vision for this landscape, but instead we think of them as having diverse views on the landscape and its development. Such approach allows to better capture these diverse perspectives within the same group of stakeholders and thus higher changes of representing existing plurality of values. By using different methods of data collection and combining said data we are able to address different groups within the residents community. It also allows to account for not only the “what” but also “where” in terms of desired outcomes. The next step in such process would be to present results of this visioning process to different stakeholders and engage them in deliberation towards a (set of) shared / joint visions.

Building Blocks

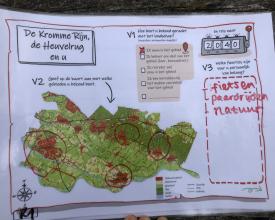

In-person participatory mapping interviews with art-based elements

This building block aims to collect necessary data from a diverse group of local actors (stakeholders, residents and others) that will allow to identify their visions for the landscape and protected areas in it. To do so we employed in-person interviews with elements of participatory mapping and art-based visuals. To guide the interviews, we used an approach called STREAMLINE, a series of A3 laminated canvas on which respondents were answering questions. This questions and canvas were organized around a narrative making it more intuitive and engaging for respondents. They started with establishing their relationship to the area, which parts of it they knew and then progressed to asking questions about importance of different landscape functions and how and where respondents wanted this landscape to develop.

Enabling factors

Such approaches as STREAMLINE that obtain data by using more interactive format can put respondents at ease, allow them to imagine the situation rather than answer a series of questions and overall have a more involved and satisfactory experience. Inclusion of mapping elements serves two purposes – not only it ensures that respondents are considering a specific place when responding to questions, but also allows them to recall elements that otherwise might not have been mentioned.

Lesson learned

Such interactive methods are suitable for obtaining data on what stakeholders value in the landscape and where these values are located. They are also appealing to wide audience and can be used both with lay-people and experts, people of different age groups. They create a more relaxed and less scientific atmosphere, while still capturing necessary information. However, in order for it to work, several points need to be considered. The most important being that canvas need to be pre-tested several times in order to make sure that the storyline is clear and easy to follow.

Resources

Online participatory mapping surveys

This building block aims to complement previous one in collecting data that is then used to collate existing visions for the landscape and PAs in it. 2020 has demonstrated that in-person interaction is not always a possibility and thus other modes, such as online ones need to be employed in order to achieve the same goals. In case of our study it was clear that in order to reach wide audience and cover as diverse of a group as possible, we also needed to employ online surveys. We have created one with elements of mapping, using specially designed platform for such tasks, Maptionnaire. This survey has followed up on several aspects already covered in interviews (see building block 1) such as different values people see in the landscape. This was done to create a baseline and see if samples in both online and in-person surveys are similar in their valuation of the landscape. In addition online survey covered such aspects as perceptions of quality of life in the area (for example, noise pollution levels, availability and quality of nature areas) and asked participants to pin-point on the map areas where landscape change occurred in last 20 years, both they considered positive and negative.

Enabling factors

Using online surveys allows to reach a different audience – in our case these were local residents, whom we might not have met in the nature areas or town markets when conducting in-person interviews. Inclusion of mapping elements allows participants to indicate which elements they value and where these are located.

Lesson learned

Option of filling the survey out in the comfort of their home on their own time is a clear advantage of this method. There are risks associated with online surveys, such as skewed sample (often including a larger share of younger people). Modes of distribution of such surveys are challenging. Replying on simply social media, while also targeting specific area might not always yield needed representative sample size. Often it needs to be complemented with other modes, for example, mailing out invitations to local residents. Access to such data (on residents and addresses) might not always be possible (depending on national and regional policies). However, in combination with other methods we believe that it provides important additions to the data, that otherwise could have been missed.

Resources

Researcher developed visions & space for reflexivity

This building block has two phases. In Phase 1 of the solution researchers involved in the project identify visions of desired futures for this landscape from data obtained in previous two blocks. Initial visions developed for our study area can be found in this Deliverable (see link below). These visions are never fully final, they are further improved / developed when new information is available. They provide lay of the land so-to-speak for decision-makers on different levels and stakeholders themselves of various interests in the landscape and how they collide or align together.

Second phase of this building block focuses on reflexivity – both among researcher team members who have developed these visions and ideally also a few stakeholders. For the former such reflexivity is needed to identify and be aware of all possible biases and preconceptions that they have introduced in visions while analysing data and developing them. For example, often if a researcher has worked in the area for a long time, they might rely on knowledge that was obtained outside this data collection and this needs to be acknowledged. Reflexivity among stakeholders on the other hand is needed in order to 1) validate developed visions, 2) foster a deliberation process during which new / modified visions representing shared or joint ideas could emerge.

Enabling factors

Development of visions for the landscape is an iterative process that is never fully complete, any changes in the landscape or arrival of new information can set another circle of re-evaluating and development of visions. With changes constantly occurring in the landscape, policies, stakeholders this presents a suitable tool of taking stock every so often in order to better guide decision-making. This solution presents a set of approaches that can be used to develop visions from data, that is often anyways collected.

Lesson learned

N/A

Resources

Impacts

Inclusive conservation is part of the long-term strategy for a more harmonious alignment of different use interests and development of shared visions for the Utrechtse Heuvelrug and Kromme Rijn region. Using the STREAMLINE narrative approach and elements of participatory mapping we have conducted interviews with different stakeholders such as decision-makers as a local level, recreationists and residents. In these interviews we focused on their perceptions and visions for the area.

As a result we have identified four main visions:

- an inclusive landscape for sustainable living,

- productivity-oriented landscape,

- a peri-urban landscape of convenience, and

- environmentally-friendly landscape. Across these visions several tensions have emerged such as biodiversity conservation vs intensive farming (specifically nitrogen pollution), timber harvests in the National Park vs recreation and aesthetics, tranquility vs recreation or new roads or other infrastructure.

Additionally, potential spatial conflicts for land have been identified between infrastructure, energy production (i.e. wind mills), farming and biodiversity conservation. In next step we will map consequences of these visions and trade-offs. Such knowledge will then be used to co-develop shared visions for the area.

Beneficiaries

- Local residents

- Visitors

- Governing bodies of National Park

- Other nature areas and local stakeholders

Story

Inclusive conservation (an approach developed within the ENVISION project) is part of the long-term strategy for a more harmonious alignment of different use interests and development of shared visions for the Utrechtse Heuvelrug and Kromme Rijn region. During our work in the area we have identified four main visions that outline different combinations of interests in the area (see Visions deliverable for descriptions):

- “An inclusive landscape for sustainable living”,

- “Productivity-oriented landscape”,

- “A peri-urban landscape of convenience”, and

- “Environmentally-friendly landscape”.

Multifunctionality is both an inherent feature of this landscape, and also one that is desired and appreciated by actors. All visions feature the importance of multiple functions, however in each of them different emphasis is put on each of them.

While identifying stakeholder values in the area we also inquired about tensions they recognize. These represent an important component of visions, as navigating these tensions is the task for local decision-makers and actors themselves. We found that many local actors (also including lay-man) are aware of a number of main tensions in the area. Across these visions several tensions have emerged such as biodiversity conservation vs intensive farming (specifically nitrogen pollution), timber harvests in the National Park vs recreation and aesthetics, tranquillity vs recreation or new roads or other infrastructure. Additionally, potential spatial conflicts for land have been identified between infrastructure, energy production (i.e. wind mills), farming and biodiversity conservation.

This awareness of existing tensions combined with desire for multifunctionality in a densely-populated mosaic of land uses of a peri-urban landscape presents a challenge for everyone involved. Acknowledging that “not all is possible” and that compromise between functions can jeopardize it all could help starting discussions on joint / shared visions and pathways towards them.