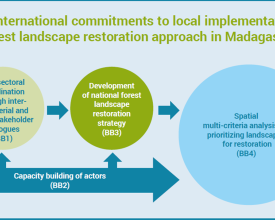

From international commitments to local implementation – the forest landscape restoration approach in Madagascar

The wellbeing of people in Madagascar depends on its natural resources and its goods, such as fuelwood, food and water. Many areas are heavily degraded due to unsustainable land use. Climate hazards add more risks for people, nature and the entire economy. Forest landscape restoration (FLR) is a key priority under AFR100 to ensure sustainable development. Resilient & multifunctional ecosystems improving the economy, food security & water supply, biodiversity protection and carbon sequestration are its cornerstones. Moving rapidly from pledges to practical implementation is crucial. This solution describes this successful process, covering the establishment of multi-stakeholder platforms, capacity building measures of actors, developing a national FLR strategy and prioritizing areas based on a multi-criteria assessment. Future steps will include identifying sites for piloting restoration activities in Boeny region.

Context

Challenges addressed

A high demand for food and fuel-wood causes deforestation and land degradation, leading to soil erosion, productivity losses and lack of water regulation. Additional climate change hazards exacerbate environmental degradation and risks for the livelihoods of people (environmental and social challenges).

Most policies address land productivity but local actions are not well coordinated; there is a lack of clear roles and responsibilities of the public sector & civil society. Overlapping land use rights and silo thinking are still predominant. The institutional framework for natural resource management is inadequate, relevant knowledge and personal and financial resources is lacking. Development needs and challenges limit land use options (governance challenges).

Good practices for landscape restoration exist at local level; but these initiatives are very site specific and lack sustainable financing for scaling them up to a broader level (technical challenges).

Location

Process

Summary of the process

The creation of the national FLR committee and platform as institutional structures for multi-stakeholder coordination and dialogues (BB1) was the foundation for moving from the FLR pledge to policies and planning of restoration. Capacity building (BB2) was provided throughout the process to support the development of the national forest landscape restoration strategy (BB3) as the framework document for further identification and prioritization of landscapes for restoration by the spatial multi-criteria analysis (BB4).

Building Blocks

Inter-sectoral coordination through inter-ministerial and multi-stakeholder dialogues

A multidisciplinary national FLR committee was set up as an advisory board, facilitating intersectoral & interministerial coordination to moving from the FLR pledge to concrete policies and action. It consists of 15 persons including the ministries of environment, agriculture, energy and water, spatial planning and representatives from civil society and the private sector.

It covers five working groups dealing with i) forest management, ii) water, iii) agriculture, vi) financing and v) soil management. It validates all key decisions. Members also participate, as resource persons, in technical capacity building activities.

The committee conducted a stakeholder and capacity needs assessment, funding analysis and facilitated various multi-stakeholder dialogues e.g. for the development of the national forest landscape restoration strategy and ensures that the interests of involved stakeholders are considered.

The FLR platform is a multi-stakeholder dialogue forum with more than 50 members, led by the FLR committee, to discuss, propose and validate practical solutions for forest landscape restoration at regional and local level and support the implementation of the FLR strategy and capacity development.

Enabling factors

- FLR focal point was appointed immediately after the AFR100 pledge in 2015, to lead the process; he was the key person and a driving force, due to the very good network with different ministries and stakeholder groups, acting as institutional knowledge broker, networker, keeping up the political momentum

- Strong synchronization of different concepts, policy coherence due to interaction between focal points responsible for different commitments, such as mangroves, UNCCD, etc

Lesson learned

- It was crucial to agree on a common definition for ‘landscape’ as a watershed unit; actors used it in very different ways in the past

- Existing spatial planning only covers administrative divisions while the landscape approach uses watershed divisions. Consultation with the Ministry of Planning were required to adopt landscape approach and results of this solution in the national spatial plan

- FLR is a multi-sectoral landscape concept, integrating various stakeholders; at the beginning, the platform only focused on forest and environment sector. It was crucial to ‘open up’ for other sectors e.g. spatial planning and water

- Restructuring of the committee was relevant to reflect FLR priorities such as land tenure, water, soil rehabilitation & ensure the capacity building

- Establishing thematic subgroups (soil, land tenure, water, forests) allowed better operationalization

- High level of participation from different stakeholders ensured legitimacy of outputs

Capacity building of actors

A series of trainings for national decision makers was conducted covering topics such as FLR terms & definitions, strategies addressing drivers of degradation (e.g. wood energy), as well as financing options. Capacity building was conducted continuously and had a ‘training on the job’ character; it was aligned with concrete aspects such as FLR studies (ROAM study, financing options), the national FLR strategy and identification of FLR priority landscapes. ~40 relevant actors (universities, civil society, private sector) were able to provide their input in the form of questionnaires on how to define priority areas for FLR, which was a cornerstone of capacity building.

The training was complemented by the participation of national representatives at various FLR & AFR100 regional and international conferences; this enabled further knowledge exchange at global level to improve national strategies.

At present, capacity building focuses at the regional level; a training module has been developed and tested in Boeny region in April 2018 and will be adapted for application in Diana region. Additional trainings will be held for the Ministry of Spatial Planning, covering land governance.

Enabling factors

- An assessment of stakeholders and capacity needs was conducted and completed (06/2016)

- High personal experiences and technical abilities of the RPF National Committee members were great assets for the capacity building. They acted as trainers and external resource persons were not necessary

- High political commitment from partner side

- Support of BIANCO (national independent anti-corruption agency) to improve transparency in the forest sector (until late 2016)

Lesson learned

- The trainings and regular exchanges helped to create a common understanding about the FLR concept as a multi-sectoral landscape approach and its practical implementation in Madagascar at policy, strategy and practical level

- It was crucial to increase the knowledge about the RPF approach based on international discussions and local realities. Each actor had own definitions of "landscape"; capacity building on the approach proved essential to ensure the same level of information for all stakeholders, especially those in sectors other than the environment

- The innovative aspect was that members of the National Committee dedicated a lot of time and also actively participated in the development of training modules and capacity building.

- The implementation of capacity building was highly participatory and the content was improved continuously by participants, also adapting the ‘language’ of key sectors such as land use planning and finance

Development of national forest landscape restoration strategy

The national strategy for forest landscape restoration and green infrastructure was developed in a participatory manner during 8 months at various stages:

1) scope definition at committee level & drafting of terms of references, selection of advisors

2) validation of methodology,

3) consultation of government, civil society and private sector at regional level (10 of 22 regions),

4) 2 validation workshops at national level for committee & platform,

5) communication of the strategy at the level of the Council of Ministers (meeting of all Ministers and Prime Ministers)

6) dissemination on the website of the Ministry of Environment and Forests.

The strategy takes stock of the current situation and framework conditions in Madagascar, analyses the main challenges to reach the 4 M ha goal by 2030 and gives strategic advice on how to overcome them and mobilize key actors.

The strategy recommends priorities covering good governance, coherent spatial planning, technical restoration measures and resource mobilization. Priorities are broken down into 12 objectives and concrete activities.

Enabling factors

- A study on FLR opportunities – following the IUCN Restoration Opportunity Mapping methodology - from 2015 served as a technical basis

- Strategy development coincided with the revision of the "new Forestry Policy" of the Ministry of Environment and Forests. FLR is a key priority for this new forest policy

- A new national energy policy supports the implementation of FLR strategy by a restoration of 40,000 ha forests and forest plantations per year for domestic rural energy supply

Lesson learned

- It was crucial that the strategy openly names challenges and potential for improvement, also including the issues of land (tenure) rights the current lack of cross-sectorial cooperation and weak governance, reflecting the awareness of existing problems

- For its acceptance and legitimacy, it was crucial to develop the key elements of the strategy in a participative process together with the FLR committee

- It was ideal that strategy was validated officially by an inter-ministerial decree involving key sectors; but this was not sufficient and additionally a long process of lobbying inside the powerful key ministries concerned was required. Integrating the secretaries general of the Ministries of Agriculture and Regional Planning into the RPF Committee was the solution for mainstreaming the strategy

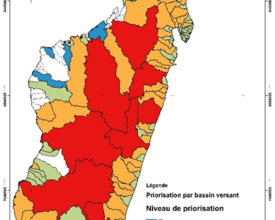

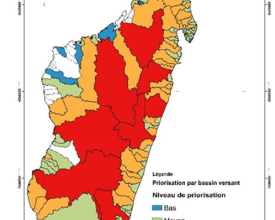

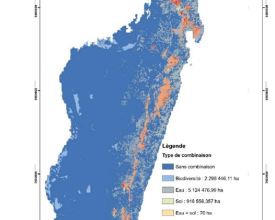

Spatial multi-criteria analysis for prioritizing landscapes for restoration

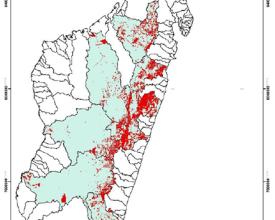

The approach focused on 3 essential ecosystem functions: water, biodiversity and soil. The following steps were used to define criteria for each group:

- Identification of ecosystem service relevant parameters and criteria (> 100 criteria)

- Pre-screening: spatialization of parameters at national, regional and local scale (41 spatially available criteria)

- Consultation: selection of final criteria based on 3 groups (water, biodiversity, soil) during group work, direct consultations; prioritization, indicator weighting and determination of criteria values (28 prioritzed criteria). Criteria examples: rainfall, hydrological resources, population density, land use, soil carbon and productivity

- Multicriteria analysis based on quantitative and qualitative values; preparation of 14 scenario maps, combining different groups (water, biodiversity and soil) with four priority levels; identification of priority area of 11,122,540 ha

- Verification of results based on data from the national restoration opportunities assessment method (ROAM) study and other sources

- Validation of results by the national FLR committee & platform and selection of 8 priority watersheds

Enabling factors

- Existing policy and planning documents defining general FLR opportunities

- Analysis of financing options and opportunities for private sector engagement in FLR (completed 05/2017)

- FLR dialogue platform and high interest and mobilization of actors

- Moving from a forest ecosystem focused to an ecosystem approach at landscape level integrating erosion prevention and water provision

- Business as usual land use was not an option anymore as ecosystems were highly degraded

Lesson learned

- Identifying 3 distinct ecosystem function groups (water, biodiversity, soil) helped stakeholders from different sectors and institutions to understand their own role and action space in this process

- Thorough consultation & involving 38 different organizations was key to prioritize restoration areas in a transparent and participatory manner and to create consensus on the final decision

- It was crucial to find a political consensus on the most balanced geographical distribution of priority areas of 4 M ha

- The process helped to install an official definition of catchment basins distinguishing 159 watersheds

- The process was very technical, but triggered an intensive political re-flection because a holistic landscape approach was used for planning and decision-making and revealed a huge potential for FLR.

- Decisions were also guided by the current policies in the energy and environmental sector to ensure coherence

Impacts

- Decision makers perceive FLR as a holistic landscape approach that increases landscape productivity, food security, access to water, climate change resilience and preserves biodiversity

- Land governance, incl. inter-sectoral coordination at national level has been significantly strengthened

- National stakeholder’s capacities on FLR have been strengthened from shaping the national policies to practical identification of landscapes for restoration; it helped to plan existing technical and financial resources in a spatially clearly defined area; they became aware of necessity for multisector cooperation to implement FLR activities sustainably

- Synergies with other policies (such as renewable energy via fuel wood provision) were used;

- New sectoral policies are being developed with a higher sense for coherence between different approaches and concepts (e.g. national directive for reforestation)

- Political awareness for FLR approach as well as political momentum for restoration have been significantly strengthened

In Boeny Region a “pilot FLR landscape” was set up with a multi-actor dialogue covering restoration from different thematic angles (land tenure, soil protection, restoration) and first steps to move from national to regional level

Beneficiaries

- National ministries (MEEF, MATSF, MINAE, MEAH) and regional offices

- Different members of the national FLR committee

- Subnational extension services

- Civil society organizations and local communities

Sustainable Development Goals

Story

By Julien Noel Rakotoarisoa, FLR Focal Point, (Ministry of Environment, Ecology, and Forests (MEEF), Madagascar)

The evolution of the forest landscape restoration process has made remarkable progress in Madagascar since the country's declaration of commitment to restore 4 million hectares of land and degraded forests by 2030. Indeed, the preparatory phase was approached with the relentless coordination of the Ministry in charge of forests, which is managing the process with the support of the German-Malagasy Sustainable Management of the Environment Programme (PAGE) implemented in cooperation with GIZ.

The key to a successful launch of FLR process lied in the dynamic nature of our multi-sectoral national FLR committee, which also involves various actors from different sectors and bachgrounds; this helped to ensure a holistic land-use planning considering the interest of each group of actors through the targeted ecosystem services approach of future restoration actions.

In addition, the development of a training program on the landscape approach, natural resource management and land use planning followed by the organization of capacity building sessions on these themes was key; it was truly based on the request of sectors concerned. This gives a lot of optimism to approach the critical phase towards the changeover from current planning into the operational phase already marked by pilot projects to implement FLR process in our country.