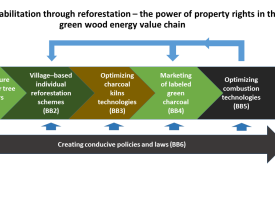

Land rehabilitation through reforestation – the power of property rights in the green wood energy value chain

Meeting the rising wood energy demand is a challenge and driver for deforestation and forest degradation. Forest landscape restoration (FLR) & AFR100 committments also address the sustainable production of wood energy to meet social and economic realities.

This solution applies a holistic view of the wood energy value chain by addressing all stakeholders in an adapted manner. Smallholder afforestation is at the heart of the solution. It combines legal, governance, economic and technical elements from land title transfers and individual afforestation schemes on degraded land at village level, to fuelwood harvesting, energy efficient charcoal processing, conversion, distribution and marketing, all the way to end-consumers & related combustion technology (improved cookstoves).

It modernizes the wood energy value chain & generates benefits for forest stewards, producers of improved stoves and end consumers alike. Their annual income has doubled on an average.

Context

Challenges addressed

- Deforestation and erosion have degraded many fertile soils during the last two decades. Heavy erosion and frequent floods destroy paddy fields affecting food security.

- Farmers increasingly turn to charcoal production to make a living. Forests and savannahs are often illegally used, as a freely accessible resource. Charcoal production is an attractive source of income as 85% of all households depend on it for cooking. Demand will rise dramatically in the coming decades.

- Charcoalers react by intensified logging, further proceeding into fragile ecosystems like mangroves and dry forests. Inefficient traditional kilns & cooking stoves add to the excessive amounts consumed (Diana: 1,000,000 m3/a), much beyond the natural regenerative capacity.

- The resulting deforestation and degradation affects water resources, increases vulnerability to natural disasters and climate change.

Location

Process

Summary of the process

The allocation of clear land tenure rights to communities (BB1) provides the basis for the Village–based individual reforestation schemes (BB2). The combination of sustainably managed fuel wood plantations with the introduction of optimized kiln technology (BB3) allows to set up the marketing of green labelled charcoal product (BB4). The optimization of combustion technologies (BB5) via improved cook stoves allows to reduce pressure on forest resources (BB2) and costs for charcoal purchase (BB4). Creating conducive policies and laws (BB6) is a parallel process that strengthen the current green charcoal value chain and promotes further scaling up in the future.

Building Blocks

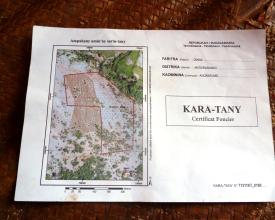

Land tenure security for tree planters

A village based participatory approval process allocates individual reforestation sites to households, along with defined use-rights & obligations using the following steps:

- Application to local forest authorities by smallholders through voluntary user groups

- Consultation on village level to exclude disputed land upfront & for taking unanimous decision on the future reforestation sites allocation. Results: minutes & sketch plan

- Verification by communal decision makers & endorsement by a communal decree

- Assigning land to the village afforestation body based on a specification document

- Mapping of individual wood lots; plot owners receive individual map with GPS coordinates signed by the mayor of the community

- Registration of sites by the land office; official verification of the reforestation site based on sketch plan, the communal decree and the enrolment into the local tenure plan.

Forest authorities register the transfer of use rights for an indefinite period, including equal access and benefit sharing for the participants. Smallholder households involved in the afforestation scheme own ~3 ha. This enables them to produce about 2.6 t charcoal per year for 27 years without further investment.

Enabling factors

- Availability of barren land not suitable for other land uses

- Involvement of the municipalities (municipal decree for the allocation of land for reforestation and decentralised land management)

- Legal framework, in particular the 2005 land reform allowing land certification through the municipalities

Lesson learned

- Awarding individual long-term land-use rights marks a new and unprecedented level of tenure security, motivation and ownership

- The number of bush fires in the afforestation zones decreased as forest owners have an interest in protecting their property

- Incomes increased by ~40% compared to average income in rural areas. For the landless third of rural farming households the increase is significantly higher.

- User groups are self-governed and operate self-reliantly, with training and organisational support (charters, administration, formation of committees, databases) provided by the project, NGOs and other local partners

- Direct monetary support is not being provided

- Land use planning helped to analyse, valuate and prioritise multiple land interests. It was the basis for a consultation process to exclude disputed land upfront, and enabled a consensus-based decision on site allocation and size

Village–based individual reforestation schemes

Planting of fast growing trees is coupled with training of personnel for managing nurseries and forests according to fixed quality standards.

Each plot is demarcated, mapped, and documented with the communities’ approval. Technical assistance is provided by specially trained NGOs in 21 months period: (i) awareness raising and social mobilisation (3 mos.); training, planning & implementation (8 mos.); self-management (10 mos.).

Choice of tree species was based on: short rotation cycles (4-7 years), resistance against climatic fluctuation, suitability for machine processing, especially on slopes, and their potential to contribute to erosion control. GIZ provided technical and administrative support on equipment and seeds needed. Woodlots were successfully planted as buffer zones around protected areas and mangroves. Further important sites for planting are watercourses and corridors on the routes of migrating fauna. Local residents now extract their wood supplies from the plantations.

Nursery operations are collectively organised; plantation and maintenance are the plantation owners’ responsibility.

Enabling factors

- Involvement of municipalities allocating degraded land for reforestation purposes, securing long-term ownership rights to plot owners (communal decree) and supporting individual land titles through their local land registry offices

- Long-term land tenure rights

- Voluntary participation of communities

- Involvement of regional administration to identify potential reforestation sites into their regional land use planning

- Technical assistance by certified NGOs

Lesson learned

- Choice of reforestation areas was deliberately on degraded areas without any agricultural potential to prevent later competition and use conflicts

- Sites were included in spatial planning & regional development plans in co-ordination with a multidisciplinary panel of public and private institutions

- Mechanised soil preparation along contour lines by tractors increased percolation of rainwater and ensured higher survival rates of seedlings

- Investment costs per ha amounted to 225 € (incl. labour investment of farmers) of which 66% are borne through technical assistance

- Rehabilitating formerly degraded land & management, promotes stewardship by communities and creates incentives for sustainable approaches in forestry

- Reforestation of degraded sites not only reduces pressure on existing forest resources, but also counters erosion and other impacts especially in close vicinity to protected areas

Optimizing charcoal kilns technologies

Improved traditional kilns and high performance retorts such as the stationary “GreenMad Dome retort” were introduced. The retort has a proven efficiency rate of more than 30% compared to traditional kilns. The internal rate of return (4,500 €/unit) exceeds 40%, a 3 times higher output. New climate-friendly kilns with methane recycling cut carbonisation time from 7 days to 72 hours. Micro credit services were provided by local microfinance agencies (OTIV) and the use of alternative fuels such as chips, briquettes and pellets were demonstrated.

Forest owners and charcoalers organised themselves as shareholder groups, create a registered micro-enterprise to invest and run the retort, and commercialise the produce on the basis of a rural energy market.

The business plan of the established company is based on the plantation management plan. Producers pay duties to the commune & taxes to the region. Several rural energy markets join forces to establish an urban charcoal market and facilitate traceability by creating a “green value chain”. Economic returns increased by ~30% compared to traditional marketing structures.

Enabling factors

- A consensual wood energy modernisation strategy for the region („Vision 2025“) on local wood energy markets, industrialisation of carbonisation processes, avoiding uncontrolled logging in primary forests

- Fast-growing plantations managed with short rotation cycles yield large quantities of wood

- Involvement of beneficiaries in research/action process to see the differences of efficiency gains compared to their usual technology

- Two-level know-how transfer (trainer to users, users to users)

Lesson learned

- Instead of prior traditional kilns that operate on a rate of effectiveness of 10-12% and waste large portions of resources, charcoal burners in the project area use improved kilns with effectiveness rates of up to 35%

- Another advantage of the retort is that it avoids CH4 emissions by recycling flue gases that would be normally emitted into the atmosphere. Because of the high global-warming potential of CH4 (21 times that of CO2), this technology yields significant CO2-equivalent reductions

- The introduction of improved kiln technologies gave the local producer associations the financial leeway to get further involved in woodfuel marketing, reap benefits and include sustainability standards. Furthermore, they are able to comply with financial rules and obligations as they got formalized

Marketing of labeled green charcoal

The “Green Charcoal Chain” concept responds to structural market distortions by guaranteeing producers (as members of local trade cooperatives) higher purchase prices for sustainably sourced charcoal. Specially established rural markets enable producers to sell wood fuel and charcoal exclusively with a proof of origin. The “Charbon Vert” label documents that labelled products have been certified against verifiable standards.

The direct cost of afforestation amounts to EUR 225/ha, of which farmers contribute about one third through their own labour. The remaining 65% are subsidised. Measures to formalize wood energy markets include penalty surcharges for illegally/non-sustainably sourced products, differentiated fees and charges (levied on transport, conversion and trade) as well as the further promotion of public-private partnerships.

Enabling factors

- Using existing or creating new institutional structures to enhance participatory decision-making processes, supporting the formalisation of the value chain & promoting private entrepreneurship

- Tax reduction for sustainable charcoal as a strong financial incentive

- Existence of legal frameworks for reforestation & charcoal production from plantations (free permits granted by the forest department)

- Availability of resources & charcoal producers ensuring the valorisation of plantations

Lesson learned

- The charcoal trade is often dominated by tight networks of middlemen (transport businesses, wholesalers, retailers). They are able to control market prices and to forestall the trickling down of economic benefits. Promoting farm-gate sales redirects a greater share of revenues to communities. Incentives for farmers and charcoal burners to set up formalized small rural businesses strengthen their bargaining power and market shares. They also facilitate proving the sustainable origin of the coal produced

- Until use regulations and taxation take effect, sustainable charcoal suffers a competitive disadvantage compared to charcoal from non-regulated and non-sustainable sources

- As long as consumers refuse to pay higher prices for sustainable charcoal, the wood energy value chain may be tied, if its value as emission reduction measure is not taken into account.

Optimizing combustion technologies

Decentral manufacturing and dissemination of energy efficient improved cook stoves (ICS) was supported including the development & testing of even more efficient, cleaner and safer combustion technologies.

The stoves save ~1,600 t of charcoal p.a., worth a total of EUR 187,500 or EUR 15 per household (which corresponds to a 25% drop in expenditure). Alternative sources of energy such as LPG are tested. Retailers and end consumers receive information and advice, partly in the context of public-private partnerships.

A women’s association (15 members) was created to promote the use of ICS in households. It focuses on educating households about the environmental and health hazards associated with traditional stoves & benefits of ICS. Most of the established ICS production sites and selling points are run by women. A panel comprising 150 households has been established to monitor annually the consumption pattern as well as the adoption rate of ICS. To date, around 12,500 families (about 30% of all households in Diego) use ICS. Instead of 117 kg/pers./yr., the households only consume 89 kg/pers./yr of charcoal.

Enabling factors

- Agreements and harmonisation with approaches of other donor supported projects (e.g. World Bank UPED project for the introduction of improved metal stoves adapted to the culinary practices of households)

- Meticulous quality assurance to meet efficiency and safety standards

- Growing market price of charcoal

- Demand from certain households for new types of improved stoves, particularly in clay, which are more efficient than improved metal stoves

Lesson learned

- The project intervened at all levels of the ICS value chain from production to commercialisation, by supporting private entrepreneurship and public relations activities

- Benefits from technological innovation must outweigh the inevitable inconvenience and socio-economic hardships associated with the adoption of improved stoves (high investment cost for the consumer/ drop in sales for the charcoal producer)

- The challenge lies in designing improved cook stove (ICS) types that, while being compatible with established cooking habits and nutritional routines, readily lend themselves to manufacturing by local artisans

- Manufactures of improved stoves require coaching and business development support so as to clear the hurdle of establishing start-up small and medium enterprises (SMEs)

Creating conducive policies and laws

A system of decentral supervision and control through local forest authorities and enforcement patrols in the villages has been set up. Awareness raising against illegal practices was strengthened. Public controls of transport routes to consumption hotspots and markets ensure that charcoalers, transporters and retailers are motivated to use sustainably sourced wood.

The strategic orientation on green charcoal value chains has been laid down in a Regional Modernisation Strategy (Vision 2020) for the DIANA region. The strategy was the outcome of a negotiation process with main actors of civil society. Key elements include improved forest management, reforestation & introduction of efficient technologies and the development of local wood energy markets.

Proposals for regulatory measures were made to curb unregulated and widespread production of wood energy in remaining natural forests. An environmental coordination platform (OSC-E/DIANA) reuniting all relevant actors of the civil society of the DIANA region has been created. The members of the platform gather regularly to discuss the progress of the modernisation process and to negotiate how to overcome upcoming barriers.

Enabling factors

- Awareness of policy makers to foster wood as a renewable source of energy

- Good governance and tenure security, esp. self-determined allocation of wastelands to households committed to their reclamation and sustainable use

- Multi-stakeholder coordination (regional biomass energy exchange platform - PREEB) to promote coordinate the implementation of the regional woodfuel strategy

- Enhanced law enforcement and transparency enhancing market competitiveness of sustainable charcoal

Lesson learned

- Formulation of a regional woodfuel strategy has to be based on a consensual vision, high-level commitment and ownership, and sound baseline information. The strategy must combine the modernisation of “upstream” and “downstream” aspects of the value chain

- Value chain development must be backed up with policy support and business development

- Value chain development needs to be incentivised through fiscal exemptions during the start-up phase; at later stages, parties to the value chain will be able to contribute funds to their respective municipalities

Impacts

Social & economic:

- 40,500 people in Antsiranana (~every 3rd citizen) have access to sustainable household energy; they benefit from reliable supply, lower fire & health hazards (less indoor air pollution)

- 12,500 households (~45,2000 people) use improved cook stoves; they save ~1,600 t of charcoal p.a., worth a total of EUR 187,500 or EUR 15 per household (= 25% less expenditure)

- The economic situation of landless poor & women was strengthened due to increased forest ownership

- Regional development was strengthened by innovative community organization & empowerment

Environmental:

- 4,200 households afforested 9,000 ha of wasteland around 68 villages and soil fertility and water retention has been improved

- Sustainable woodfuel production on 9,000 ha already offsets unregulated exploitation of more than 90,000 ha of natural forests, in and around protected areas

- About 1,000 ha of forest area are sustainably used per year. A total of 4,700 t of green charcoal can be produced

Scaling up:

- The approach is currently scaled up in other regions of Madagascar on 15,000 ha; Cameroon and Ghana have initiated a replication

Beneficiaries

- 4,200 individuals from ~70 villages (reforestation)

- 275 charcoal producers (members of local trade cooperatives)

- 12,500 households (~42,000 people) use improved cookstoves

- 40,500 people have access to better wood energy

Sustainable Development Goals

Story

Doudou - the green business man: Without charcoal, most stoves of Malagasy kitchens would remain cold; especially city dwellers depend on it. ~85% of households cook with charcoal. It is unlikely that things will change in the near future. Only 14% of households are connected to the electrical grid and only a minority can afford to buy gas.

A large number of people in the countryside round off their meager income by making charcoal. They get it illegally from the nearby forest with negative consequence to the environment. It hardly rains and the environment suffers a lot, gusts of wind can trigger bushfires. During periods of rain, soil is washed from the slopes into the rice fields. All of this is seriously damaging our future.

Abdou Mockbel – or Doudou as his friends call him - also produced wood illegally before. In 1996, he heard about the green mad kiln technology for the first time. He and his wife Odette were taking part since the beginning.

4200 households have participated since its launch. They mainly plant eucalyptus trees on a surface of 9000 ha. They decide on which plot the trees should be planted; soils already degraded can be used again and can be protected against erosion damage. They first produced seedlings together and then transplanted them.

The Program facilitated a rapid and easier administrative process of land titles granting at affordable prices. Abdou and his wife had it after only 2 months. Abdou now produces his charcoal from a modern oven. It can produce twice more coal than a traditional oven and almost four times faster.

Thus with the help of GIZ, Abdou created with other plot owners a cooperative with their own point of sale. Each month, they now sell up to 1000 bags of sustainably produced charcoal.