Restoration of mangroves for food security in the Gancho Murillo coastal State Reserve Chiapas, Mexico.

In order to reduce the vulnerability to climate change of communities on the coast of the State of Chiapas, ecosystem-based adaptation (EbA) measures were implemented with the communities of Ejido* Conquista Campesina, located in the Gancho Murillo Zone Subject to Ecological Conservation (state reserve).

The measures were designed to raise awareness about the value of mangroves and improve their condition through restoration actions. The clearance of water channels, allowed water to flow and increase the overall fishing area, benefiting communities’ social resilience and food security. The work with the fishing communities involved an "action learning" approach, which allowed the community to actively participate, take ownership of EbA measures and assess effectiveness in protecting local livelihoods. This in turn strengthened the communities social cohesion, local governance, institutional relationships, and leaders’ advocacy capacity.

*Ejido: land-tenure communal structure in Mexico

Context

Challenges addressed

- Deforestation in the upper watershed of the Cahoacán River generates erosion and decreases the soil’s water infiltration capacity, which combined with changes in rainfall patterns and intensity, increases runoff and sediment deposition into downstream coastal ecoystems.

- Conquista Campesina has 828 ha of common lands that include mangrove ecosystems, which are at risk due to the high rate of deforestation (resulting from the expansion of the agricultural frontier and illegal logging), as well as excessive sedimentation (siltation). This sedimentation not only harms the mangroves, but also contributes to the frequent flooding of villages.

- The advancement of saline waters due to rising costal water intrusion that enter the wetland generates an ecological imbalance that affects the mangrove’s natural regeneration and reduces water quality for human consumption.

- The ejidal assembly’s representation bodies and leaders require greater capacity for political advocacy before government entities.

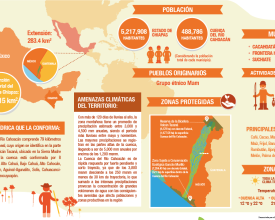

Location

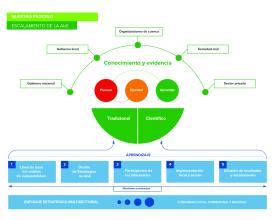

Process

Summary of the process

This solution for a coastal ejido in Chiapas is presented through 3 Building Blocks (BB): 1. Action learning, 2. Socio-environmental resilience, and 3. Governance.

The implementation of EbA measures (BB2) and governance for adaptation (BB3) are achieved by mobilizing the support of community structures under a "learning by doing" approach (BB1) that combines training, field actions (restoration, surveillance, productive diversification), participation, monitoring and valuing of mangrove ecosystem services. Restoration actions improve conservation state of mangrove ecosystems, with direct results for local livelihoods (fishing, collecting) and ecossystem based disaster risk reduction. The restoration has proofen to increase resiliency to climate variability and decreases food insecurity is observed. At the community level, a process of collective learning and empowerment ensues, with the acquisition of technical knowledge, leading to progress in the ejido’s governance and its capacity for political advocacy, up-scaling and accessing financial resources, and the strengthening its adaptive capacity. Contributions are also made to good governance of the coastal zone by creating cooperation between local, state and federal agencies.

Building Blocks

"Action learning" and monitoring to increase capacities and knowledge

Supporting ejido community members to implement EbA measures generates a process of "action learning" that, in addition to teaching, aims to generate evidence on the benefits of EbA and create conditions for their sustainability and up-scaling.

- CRiSTAL Community Risk Assessment

- Mangrove restoration (4.1 ha) and surveillance are considered priority EbA measures.

- Technical support is provided to 33 community members (men and women), complemented with their traditional knowledge, to learn about mangrove restoration techniques and carry out the restoration of degraded areas.

- 5 community technicians are trained to monitor and evaluate the restored areas (measurements of tree diameter, physical-chemical parameters and sediments).

- Monitoring and evaluation is carried out to learn about the food security with 10 families (sample) and study the benefits of restoration on livelihoods on dry and rainy season. Household social surveys used as methodology (guidelines to be published).

- Joint learning on the advantages of income diversification, such as gardens (orchards), agroforestry and beekeeping.

The increase in capacities and knowledge strengthens human capital and contributes to community empowerment and with that, to more possibilities for political advocacy and accessing financial resources.

Enabling factors

- Some members of the Conquista Campesina ejido had previous experience working with good ecological management practices and/or had participated in the local Payment for Environmental Services scheme (coordinated by Pronatura Sur A.C. and CONAFOR). This facilitated the acceptance of restoration actions by community members.

Lesson learned

- When implementing the monitoring and evaluation baseline for food security and its improvement through EbA, many ejido members realized that it was important to manage their territory integrally and not only ensure the protection, conservation and restoration of the mangroves. This awakened interest in diversifying the crops used in family plots, and the understanding that this measure would improve family alimentation and expand income sources.

Increased environmental and social resilience through mangrove restoration

The ejido Conquista Campesina wanted to restore mangrove forests and the ecosystem services that these provide (biological diversity, water quality, protection against storms) with a view to strengthening its food security and resilience in the face of climate change.

The opening of hydrological channels was first carried out to replenish with water areas damaged by sedimentation; then the collection, translocation and sowing of propagules in the degraded areas was coordinated. Through the ‘payment of laboured days’ as restoration incentives (Payment for Environmental Services), these efforts also achieved economic benefits for the community. While the water open surface was improved in fishing areas, the community was also protecting itself against winds and storm surges in areas used for collecting, fishing and housing. In addition, family gardens (orchards), agroforestry and apiculture were implemented in some plots to diversify the products used by families for self-consumption. These processes provided important means of learning for ejido members, both men and women, who acquired technical knowledge (on mangrove restoration and managing plants in association) and a better understanding of the relationship between climate change, conservation and food security.

Enabling factors

- Ejido Assemblies are very strong institutions within the communities of the State of Chiapas. Their authority and decisions are key to the adoption of any kind of ecosystem management measure. To have the approval of the Assembly is to have the support of the entire community.

- There is a local payment for environmental services scheme (through concurrent funds and coordinated by Pronatura Sur A.C. and CONAFOR) that supports the restoration, protection and surveillance of mangrove ecosystems (~500 ha overall).

Lesson learned

- The possibility of accessing an economic incentive, in the form of ‘payments for laboured days’, was motivational and an effective means to achieve the restoration of 4.1 ha of mangrove forest in Conquista Campesina.

- Restoration efforts awoke the interest of ejido members in other opportunities such as the implementation of family gardens (orchards), agroforestry and beekeeping on their plots. These changes (the acquisition of new knowledge and products for self-consumption) turned out to be convincing for families, as they could reduce their dependency on fishing and the mangrove ecosystems.

Strengthening governance for adaptation

Within ejido community structures, the ejido assembly acts as a governance platform and is the highest decision-making body. Achieving the approval of the assembly was a key step to initiating and then increasing mangrove restoration efforts in the Conquista Campesina ejido. A community program was developed for the conservation of wetlands and aquatic systems through the voluntary conservation of lands nominated as "ecological easements". Thanks to its work around the mangroves, the ejido’s organization has improved and generated more institutional linkages, both with state and federal entitites. This also opens up opportunities to up-scale adaptation needs to higher levels of government. With this aim of political advocacy, ejido members participated in the VII National Congress on Climate Change Research, sponsored by the recently re-activated Chiapas Climate Change Advisory Council, to present the benefits of EbA as well as proposals for their priorities to be taken into account in the State’s climate change policy. Assisting the ejido’s social organization therefore helped to enhance governance for climate change adaptation from the local to the state level.

Enabling factors

- The support of the ejido assembly favours the implementation and monitoring (M&E) of EbA measures. This is a social reseach with household surveys that is to be applied during rainy and dry season.

- The National Congress on Climate Change Research, involving the newly re-activated Chiapas Climate Change Advisory Council, offers a window of opportunity for stakeholders, such as the ejidos, to present their needs and proposals related to climate change, before different state entities.

Lesson learned

- The ejido’s organization and the technical support were key for the implementation of restoration and monitoring actions, and also in the adoption of agreements, the up-scaling of EbA, and the accessing of financial resources under federal programs (CONAFOR’s Payment of Environmental Services).

- Given the mosaic of property regimes that exist on the coast of Chiapas, the best alternatives for protecting coastal ecosystem services and local livelihoods are those derived from conservation mechanisms for which the main driving force is the active participation and empowerment of the users and owners of the natural resources.

Impacts

- Greater knowledge regarding the restoration and sustainable management of mangroves.

- Restoration of 25 ha since 2011

- Reforestation of 4.1 ha of mangroves

- Prevention of illegal logging through surveillance

- Recovery and clearance of the mangrove’s hydrological system through the clearance of 180m of water channels allowed the water to flow better along the estuary, benefiting the entrance of sea water and the reproduction of scale fish, shrimp and other species.

- Sustainability of actions thought local decision-making to increase efforts in the area.

- Economic benefits through forestry incentives, using the modality of “payments for laboured days” linked to restoration efforts.

- Research on the benefits of EbA for food security using a Monitoring and Evaluation methodology with local families.

- Policy advocacy with the presentation at the state level of the ejido* Conquista Campesina’s EbA priorities and vulnerability study.

Note: Within Chiapas governance structures, the Ejido is the main social platform where participatory decisions are made regarding natural resources. Ejido land tenure in Mexico is an example of individual and communal tenure co-existing within communities. Communal lands are titled in the name of the community leaders.

Beneficiaries

- Direct: 420 inhabitants of the ejido Conquista Campesina, with 33 community members trained in mangrove restoration and monitoring

- Indirect: 3 surrounding communities (ejidos Barra de Cahoacán, Brisas del Mar and La Cigüeña)

- Municipality of Tapachula

Sustainable Development Goals

Story

The coastal ejido Conquista Campesina is one of nine ejidos present in Gancho Murillo State reserve (area of ecological conservation), where there are still 7,284 ha of mangrove left (compared to ~132,000 ha in State of Chiapas). Despite being under protection, the area is densely populated with ranches, communities and fisheries. The most common livelihoods are fishing and timber extraction, which is especially important for families' food security.

Mangrove ecosystems are at risk due to several factors. High deforestation rates in Cahoacán River basin that supplies water to the coastal Conquista Campesina and its mangroves, and the effects of climatic variability, in particular excessive rainfall that increases runoff and sediment deposition downstream of the basin. Additionaly, increasing sedimentation contributes to frequent flooding of communities, while coastal storm surges also put homes and fishing areas at risk. Increasing salinization of water wells due to increasing frequency of storms and other coastal hazards, which are securing water provision for coastal communities, is also an issue.

The health and regeneration of mangroves to protect coastal communities was a key aspect in finding solutions to this set of challenges. As an EbA measure, communities of Conquista Campesina supported healthier mangroves that would provide food, livelihoods, protection against hurricanes and refuge for fishing species. Initiating the mangrove restoration project in the ejido, which ultimately brought, beside climate change adaptation and disaster risk reduction, various economic, social and environmental benefits to the population of Conquista Campesina, and to some extent to neighbouring ejidos as well.

Mr. Cándido González Nafaté, technical community member of Conquista Campesina ejido, mentions the importance of promoting the strengthening of the ejido’s social organization and territorial governance when defining adaptation measures (mangrove restoration), and values aspects of participation, responsibility, transparency, efficiency and inclusiveness. In order to reduce the enormous pressure that natural resources face in the area, he proposes the creation of conditions to assist owners of forest lands upstreaM to undertake value-addition processes on their raw materials, recalling that these owners are also from highly marginalized communities in the basin.