Strengthening community leadership for mangrove restoration and food security of the Paz River, El Salvador

The hydrodynamics and course of the lower part of the Paz River were altered in the past, affecting the water supply into the river mouth and coastal mangroves. Currently, further degradation comes from deforestation and agricultural practices like sugarcane and livestock. These mismanaged activities led to inequitable use of fresh water and conflict between companies, communities and local authorities. The communities and coastal ecosystems of Garita Palmera are among the most affected.

Having assessed the decreasing water flows and the vulnerability of their livelihoods, the fishing families agreed to implement Ecosystem-based Adaptation (EbA) measures to restore coastal and mangrove forests with the support of the NGO Unidad Ecológica Salvadoreña and IUCN. The measures created awareness for the importance of ecosystem services and improved their condition through conservation agreements, restoration and community monitoring.

Solution developed under AVE project - www.iucn.org/node/594

Context

Challenges addressed

Water-related climate risks in the area are:

- Risk of flooding on the coastal plain

- Climatic scenarios foresee less rainfall and more droughts

- Diminishing of water resources availability

Sustainable production and watershed management challenges are:

- Deforestation drivers due to the introduction of sugarcane and livestock.

- Unsustainable irrigation practices of sugarcane producers

- Water wells (aquifers) and the water quality of mangrove ecosystems are showing increasing salinization

- Soil erosion and pollution problems from agriculture practices

Regarding the governance of natural resources further important challenges are:

- El Salvador lacks a specific regulatory framework for the integrated management of watersheds or water resources

- Land management instruments that would help to improve up-stream management to guarantee the availability of water downstream are absent

- In addition, the Paz River basin is shared between El Salvador and Guatemala, which requires binational coordination

Location

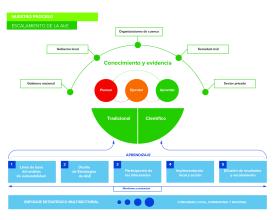

Process

Summary of the process

This solution contemplates 3 Building Blocks (BB): Water governance (BB3) and the implementation of EbA measures (BB2) is achieved by mobilizing the support of existing community structures under an "action learning" approach (BB1) that combines training, field actions, participation, monitoring, and valuing of ecosystem services. At the community level, a process of collective learning and empowerment is generated by acquiring knowledge of vulnerability, ecosystem restoration as an EbA measure, food and water security and the relevant legal and policy frameworks (BB1).

Combining the three BB results in improved self-governance of communities and their capacity for policy influencing, thus strengthening their adaptive capacity.

Stakeholders (local communities, state agencies, and the private sector) are convened towards solving environmental problems and coordinate through governance structures. Lessons from implementation of EbA measures (BB3) are shared by local leaders (through dialogue and campains) to convince the government and private sector that restoration efforts increase resilience to climate variability and decrease the food insecurity of local families.

Building Blocks

"Action learning" and monitoring to increase capacities and knowledge

Action learning is a process that involves the implementation of EbA activities, coupled with a practical capacity building program for scaling up results. The process, in addition to enhance local communities' capacities and skills, generates evidence on EbA benefits through the implementation of a monitoring system aiming at policy makers. Some elements and steps in the process are:

- Participatory assessment of communities’ socio-environmental vulnerability.

- Prioritization of mangrove restoration sites, as an EbA measure, based on assessment and in complementation to traditional knowledge.

- Participatory monitoring and evaluation of EbA effectiveness to food security. The research (22 families sample) aims to understand the benefits of restoration on their livelihoods.

- Capacity building process to strengthen natural resource management, local advocacy and adaptive capacities, through:

- Trainings and exchanges of experience on adaptation to climate change, watershed and water management, and sustainable mangrove management.

- Technical support provided to the communities, to jointly undertake mangrove forest restoration.

- Joint monitoring activities. With tangible evidence, communities are able to raise awareness and gain political advocacy capacities and access to financial resources.

Enabling factors

- Due to a weak governmental presence locally, the communities have promoted their own self-organization through Development Associations and other local structures (e.g. Environmental Committees), making room also for leadership and mobilization by women, all of which result in increased social capital.

Lesson learned

- Working with both with formal community's (e.g. through Development Associations) and other local civil society groups (e.g. Microbasin Committee) is key, as these entities have a direct interest in the success of the EbA measures to be implemented.

- Local stakeholders can facilitate dissemination of the measures, and with it, their replication, as occurred with upstream communities in the Aguacate River basin, where takeholders became interested in the measures implemented downstream and proposed the creation of a broader forum (a 'Mangrove Alliance') for the entire Salvadoran coast.

Implementation of mangrove restoration EbA measures

Under the leadership of the Istatén Association and the El Aguacate Microbasin Committee, the following EbA measures were implemented in favour of local livelihoods and their resilience to climate change.

Hereby, communities implemented their own solutions to the problems they identified, under the motto: Paz River: Life, Refuge and Food.

The measures included:

- Unblocking and eliminating sediments from mangrove channels to allow fresh water to enter and restore optimum salinity levels.

- Reforestation of degraded mangrove areas (as a result of indiscriminate felling /livestock grazing).

- Community surveillance of key sites, with persons responsible assigned rotationally, in order to prevent mangrove felling and excessive species extraction, and ensure the protection of newly planted seedlings in reforested areas.

- Design and implementation of a Local Plan for Sustainable Use (PLAS) that regulates the extraction from the mangrove of fish, crustaceans (crabs and shrimp) and mammals (periods, quantities and practices), for sustainable species management.

These measures seek to increase and manage the breeding area of those species of greatest economic interest and relevance for food. In addition, mangrove restoration has improved protection against storms and waves.

Enabling factors

Joint implementation together with community development associations facilitate decision-making and collective mangrove actions.

- Istatén Association comprises 3 communities (Garita Palmera, El Tamarindo, y Bola de Monte). It was created in 2011 with the purpose of community mangrove surveillance.

- Aguacate river Micro watershed Committee, created in 2012, works on environmental challenges with a basin approach. The group comprises 40 local representatives.

Lesson learned

- It is key to support restoration efforts with biophysical studies that provide inputs for monitoring and evaluation and better decision-making regarding the intervention sites or the measures adopted, particularly the channel dredging and reforestation actions. It is also key to complement this with the empirical knowledge of the communities, generating a base of technical-scientific-social evidence that is pertinent and sustainable.

Strengthening water governance and leadership for adaptation

There are several governance challenges in río Paz, such as institutional weak presence and weak institutional coordination which drives to the mismanagement of the river and the coastal ecosystems.

IUCN, UNES and local communities proposed a buiding block to ensure the full implementation of the solution. The process implies strenthening and articulation of governance local structurers by:

- identification of leaders

- social awareness

- consolidation of local groups such as the Istatén Association, the Aguacate Microbasin Committee, women's groups and water boards.

Governance structures develop integral operative working plans, that respond to local needs and improve socio-political and advocacy capacities. The advocacy seeks to (i) persuade the Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources (MARN) to establish sanctions for those who incur in prohibited fishing practices, and to demand greater responsibility in the use of water and management of liquid waste by the sugar industry; and (ii) request the Ministry of Agriculture (MAG) to monitor the water use of this industry (i.e. the permits extended) and to introduce water rates that are proportional to the volume used. The case has already been brought forth to the Environmental Court and is waiting for a resolution.

Enabling factors

- Presence and trust of the local partner NGO, UNES in the project region.

- Collaborative and facilitative approach with communities - as partners instead of beneficiaries.

- Learning from communities

- Strengthening of local groups. Local groups have been key actors in the work of identifying community problems, and then planning and implementing the solutions through collective actions.

Lesson learned

- For ecosystem restoration practices to be successful and sustainble, they must be accompanied by advocacy and dissemination actions that reinforce these EbA initiatives. These actions are particularly necessary in the lower basin of the Paz River, due to the existance of the environmental conflicts in the territory around water and the variety of actors involved.

- Organizing an advocacy agenda is a powerful tool for communities, especially if it contains specific proposals that aim to achieve the implementation of existing environmental regulations.

- Stakeholders need permanent negotiation spaces for ensuring continuous dialogue on natural resources.

Impacts

Local communities

- Greater local knowledge on sustainable mangrove management, restoration, climate change, water and watershed management, and food security.

- Building local social capacities though the positioning of the El Aguacate Microbasin Committee as a reference in environmental defense and ecosystem restoration.

- Community ownership around EbA measures, water defense, and local natural resources (mangrove)

- Reforestation of more than 3 ha of mangrove and improvement of the hydrological system

- Research on the benefits of EbA for food security using a Monitoring and Evaluation methodology with 22 families.

Maintreaming EbA at the national level

- Advocacy for regulating the use of fresh water and the natural assets of coastal ecosystems carried out by local communities (Microbasin Committee) with the CONASAV (National Council for Environmental Sustainability and Vulnerability), the Environmental Court, MARN (Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources) and MAG (Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock).

- Partnerships established with MARN and Park Rangers at the local level to support mangrove management activities.

Beneficiaries

- Fishing communities of Garita Palmera, El Tamarindo and Bola de Monte (Ahuachapán, El Salvador)

- El Aguacate Microbasin Committee (community association for environmental protection, formed by local leaders)

Sustainable Development Goals

Story

Feeling the wind that runs across the mangrove at 7am reminds her why she started taking care of the mangrove and the sea. "It feels fresh, before there was more heat. We have learned how to care for nature and appreciate water. Before, what I did was to cut down trees, catch small fish and shrimp, I would do damage without knowing that I was doing damage to myself, to my family and my community” reflects Maria Magdalena Del Cid Torres, who lives in the Playa Bola de Monte hamlet, in the coastal zone of the Paz River basin.

At that hour, she is beginning her day’s work of mangrove and forest surveillance. Together with another neighbour, she patrols the area by foot, taking care that no one enters to cut trees or fish indiscriminately in the mangrove. It is not an easy task for a woman: It entails more than 8 hours away from home in an isolated frontier area. For Maria, there is no criticism from neighbors or fear that will part her from her new mission. They also carry out water monitoring . "We take the temperature of the water, we measure the salinity of the water wells and how much water there is. Sometimes we are accompanied by people from UNES - the NGO Unidad Ecológica Salvadoreña, an IUCN member organization - and sometimes we go alone."

The people of the community also participate in canal clearing activities. "Dredging the canals is giving us family sustenance, we catch bigger fish and when it’s time for fishery closure, we take care not to fish. It’s a wonderful experience because the work involves women and men, young and old. It looked easy but it is hard work, to walk inside the mud and between the roots of the mangrove, but it greatly benefits the mangroves."

Maria feels her experience in the mangrove forest and what she has learnt through training workshops have taught her to understand how climate change affects her as a woman, but above all, how her work can contribute to positive change in her community.

"I was one of the women who stayed mostly at home. I feel happy because I have been given the opportunity as a woman to understand and learn new things. I am organized, I take care of our mangrove and I am a witness to the changes that we’ve achieved. In addition, I now understand that I am the one who makes my own strength; strength does not come with us, we build it ourselves, and this I did not know by just staying at home" Maria concludes.

https://www.iucn.org/es/news/mexico-america-central-y-el-caribe/201809/la-vigilante-de-los-manglares