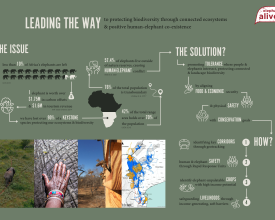

Une approche progressive pour accroître la tolérance humaine dans les corridors d'éléphants afin de promouvoir la connectivité des écosystèmes

Les éléphants explorateurs se déplacent dans des paysages dominés par l'homme, souvent au-delà des frontières internationales. Ce faisant, ils jouent un rôle essentiel en reliant les zones protégées (ZP), mais ils sont également confrontés à des conflits entre l'homme et l'éléphant (CHE) qui menacent leur vie et leurs moyens de subsistance. Notre solution propose une stratégie à long terme pour conserver les corridors d'éléphants tout en intégrant les besoins socio-économiques des personnes qui partagent le paysage avec eux. Le suivi par GPS des éléphants dans deux zones de conservation transfrontalières permet de repérer les corridors de liaison existants et, par conséquent, les endroits où concentrer les ressources. Nous utilisons des expériences innovantes de type "cafétéria" pour comprendre quelles plantes non appétissantes pour les éléphants offriraient des sources de revenus alternatives lucratives aux agriculteurs vivant dans ces points chauds du CHE. Enfin, nous combinons la sécurité alimentaire et la sécurité des personnes en déployant des unités d'intervention rapide et des barrières souples pour protéger les cultures de subsistance. Cette stratégie progressive permet de protéger les biorégions afin d'atteindre les objectifs de biodiversité à l'échelle du paysage.

Contexte

Défis à relever

Le conflit entre l'homme et l'éléphant menace la sécurité physique immédiate des éléphants et des humains, avec des morts de part et d'autre. En outre, le pillage des cultures menace les moyens de subsistance des communautés d'agriculteurs de subsistance qui vivent le long des corridors de la faune sauvage. Si rien n'est fait, d'importants corridors reliant des zones protégées fragmentées seront fermés, car les éléphants éviteront d'emprunter les corridors par peur de l'apprentissage ou à cause de barrières physiques (clôtures électriques). Il en résultera un déclin des populations d'éléphants et des effets désastreux sur toutes les migrations d'animaux sauvages entre des zones protégées de plus en plus isolées. Les lignes directrices de l'UICN soulignent l'importance des écosystèmes connectés pour permettre des fonctions écologiques essentielles telles que la migration, l'hydrologie, le cycle des nutriments, la pollinisation, la dispersion des graines, la sécurité alimentaire, la résilience climatique et la résistance aux maladies. La perte de biodiversité qui s'ensuivrait réduirait à néant tous les progrès économiques réalisés par les communautés rurales et accélérerait les effets négatifs du changement climatique.

Emplacement

Traiter

Résumé du processus

La protection des éléphants d'Afrique et de leur habitat dans les biorégions nécessite une approche multidimensionnelle et intégrée de l'engagement communautaire, de la création de connaissances et d'actions pratiques de conservation. Il s'agit notamment de cartographier les déplacements des éléphants en dehors des zones protégées afin de comprendre la connectivité des paysages, de concentrer les efforts d'atténuation dans les points chauds du CHE et de mener des expériences pour évaluer les cultures alternatives pour les communautés touchées par le CHE.

Une combinaison de barrières dures (clôtures électriques) autour de petits champs de cultures de subsistance qui n'interdisent pas le mouvement des éléphants, avec des barrières douces génératrices de revenus (cultures non appétissantes ayant une valeur marchande, pollinisées par des clôtures de ruches), peut aider à atténuer les conflits à long terme ; tandis qu'une unité de réponse rapide réactive peut assurer une sécurité immédiate dans les zones de conflit élevé. Dans les zones de pillage des cultures identifiées grâce aux données de suivi et aux informations communiquées par les unités d'intervention rapide, les agriculteurs peuvent être encouragés à n'exploiter que des cultures viables et peu appétissantes, dont la valeur marchande et le rendement sont élevés. La combinaison de barrières douces génératrices de revenus, telles que la plantation de cultures de grande valeur, avec une relation de renforcement mutuel de la pollinisation pour les clôtures de ruches, favorise les résultats en matière de biodiversité et soutient les économies rurales dans et autour des régions de corridors fauniques.

Blocs de construction

Cartographie des corridors fauniques reliant les zones protégées grâce au suivi des éléphants par satellite

Partant du constat que plus de 50 % des déplacements des éléphants se font en dehors des zones protégées (ZP) et que plus de 75 % des populations d'éléphants sont transfrontalières, nous avons utilisé une approche de suivi par satellite pour identifier les corridors de faune les plus utilisés par les éléphants.

Alors que notre plan initial était d'établir un corridor entre Gonarezhou (forte densité d'éléphants) au Zimbabwe et les parcs nationaux de Banhine et/ou Zinave (faible densité d'éléphants) au Mozambique, l'insuffisance des données de suivi et des rapports reliant les aires protégées de ces pays (du Zimbabwe au Mozambique) pour définir un corridor concluant nous a obligés à déplacer notre position géographique vers la vallée de Namaacha, dans le sud du Mozambique. Ici, plusieurs éléphants que nous avions marqués au collier en dehors des aires protégées dans l'espoir de trouver plus d'individus se déplaçant dans le corridor entre les aires protégées du sud du Mozambique, ont défini un corridor vital couvrant l'extrémité sud du KNP, le sud vers le parc national de Tembe en Afrique du Sud et l'est vers le corridor de Futi et la RSM sur la côte du Mozambique.

Le marquage des éléphants et l'analyse des données de suivi nous ont montré que les aires protégées existantes sont trop petites pour les éléphants. Le fait d'utiliser les éléphants comme planificateurs du paysage pour assurer la connectivité au-delà des frontières nationales nous a permis d'identifier les points chauds des conflits entre l'homme et l'éléphant, là où les efforts sont les plus susceptibles d'avoir le plus d'impact.

Facteurs favorables

- Des fonds suffisants pour acheter des colliers et payer les frais d'hélicoptère sont essentiels à la réussite de cette partie du plan stratégique.

- La disponibilité des hélicoptères et des pilotes peut s'avérer difficile dans les zones reculées.

- La coopération de la communauté pour savoir où et quand les éléphants se trouvent dans les régions du corridor.

- Lorsque l'on travaille dans une grande zone de conservation transfrontalière, le soutien logistique des organisations partenaires est essentiel pour une mise en œuvre réussie à long terme.

Leçon apprise

Nous avons appris que les éléphants qui se déplacent dans les couloirs sont rusés et ne sont donc pas souvent vus pendant la journée lorsqu'ils peuvent être munis d'un collier. Ils se cachent pendant la journée pour éviter les conflits avec l'homme. Nous avons réussi à trouver des animaux d'étude appropriés en posant un collier sur un ou plusieurs mâles d'un groupe de mâles célibataires près de la limite des zones protégées ou même à l'intérieur des zones protégées. Cela nous a permis de trouver d'autres animaux lorsque les groupes se sont séparés au fil du temps. Le fait de disposer d'une unité mobile de réponse rapide nous informant des mouvements d'éléphants nous a permis de fournir des colliers à la Mozambique Wildlife Alliance, qui peut les déployer rapidement et efficacement sur le terrain. Le fait d'avoir écrit à l'avance pour obtenir des fonds par le biais de subventions nous a également permis de disposer de fonds. Le temps de vol coûteux des hélicoptères et la disponibilité des pilotes sont restés un défi.

Les unités d'intervention rapide sont une solution à court terme pour assurer une sécurité physique et des moyens de subsistance immédiats.

Une unité de réponse rapide (RRU) a été mise en place pour traiter les cas urgents de CHE. La nécessité de cette unité a été justifiée par la pression croissante exercée par les autorités de district, qui n'ont pas la capacité d'atténuer les effets du CHE. Par conséquent, les niveaux supérieurs de gouvernement sont mis sous pression pour protéger les personnes et les moyens de subsistance, et ont souvent recours à la gestion létale des éléphants. Pour éviter ces interventions létales, le rôle de l'URR est de (1) répondre aux situations de CHE avec un effet quasi immédiat, (2) éduquer les membres de la communauté sur la manière de se comporter avec les éléphants et de déployer plus efficacement les boîtes à outils de CHE, (3) collecter systématiquement des données sur les incidences des attaques de cultures, les méthodes d'atténuation déployées et les réponses des éléphants afin que nous puissions développer un système d'alerte précoce efficace, et (4) perturber les stratégies d'attaque des cultures par les éléphants grâce à une planification d'intervention surprise afin de contribuer à terme à la modification des comportements. L'URR s'appuie sur les données des colliers GPS pour (1) identifier les principaux points chauds des conflits entre l'homme et l'éléphant et (2) établir des cartes de probabilité des attaques de cultures pour le déploiement stratégique de méthodes d'atténuation à long terme.

Facteurs favorables

- Financement durable et formation de l'URR et des unités supplémentaires si elles sont actives dans des zones étendues

- Augmentation du taux de réussite au fil du temps afin d'éviter les désillusions et les déceptions quant aux méthodes appliquées

- Optimisation des modes de transport et de communication pour permettre à l'URR d'être agile et de réagir rapidement

- Financement continu pour reconstituer les outils de dissuasion utilisés

- Soutien continu aux ateliers de formation et à l'appropriation des stratégies d'atténuation par les communautés

- Soutien à l'infrastructure des tours de guet et des barrières souples

- Modification du comportement des éléphants à la suite d'une dissuasion réussie

Leçon apprise

Initialement, le nombre de cas signalés a fortement augmenté à la fin de la première année de fonctionnement de l'URR. Après 18 mois, l'impact de l'URR est visible dans la proportion de 95 % d'interventions réussies au cours des six derniers mois, contre 76 % au cours des 12 mois précédents. Avec un taux de réussite de 79 % pour 140 interventions et une diminution continue du pourcentage de CHE nécessitant l'intervention de l'URR au cours des 18 derniers mois, l'URR a prouvé sa valeur pour les agriculteurs locaux. Elle a également permis aux communautés locales de disposer de mécanismes de dissuasion sûrs et efficaces pour chasser les éléphants de leurs champs en toute sécurité, ce qui signifie que le pourcentage de cas de conflit nécessitant une intervention de l'URR a chuté de 90 % au cours des six premiers mois de fonctionnement à 24 % au cours du 18e mois de fonctionnement.

Les jours de dissuasion de l'URR ont considérablement diminué, de même que les poursuites infructueuses. L'augmentation du nombre d'équipements et d'unités d'équipement utilisés peut être attribuée aux nombreux ateliers de formation au cours desquels les membres de la communauté ont été habilités à adopter diverses méthodes de dissuasion non létales grâce aux trousses à outils.

Atténuation des conflits entre l'homme et l'éléphant grâce à des barrières souples protégeant les champs de culture

En mai 2023, l'équipe d'Elephants Alive (EA) s'est embarquée pour une mission de mise en œuvre d'une barrière de protection contre les conflits homme-éléphant dans la vallée de Namaacha, dans le sud du Mozambique. EA et Mozambique Wildlife Allience (MWA), ainsi que des délégués de Save The Elephants (Kenya) et de la Fondation PAMS (Tanzanie), se sont réunis dans le cadre d'un exercice de coopération inspirant pour mettre en place une barrière souple d'atténuation à quatre voies afin de protéger trois champs de culture. Ces champs avaient été identifiés, grâce à des recherches sur le terrain et à des données de suivi par GPS, comme présentant un risque élevé de pillage des récoltes par les éléphants. Un côté de la barrière a été construit en suspendant des ruches. Lorsque les ruches commenceront à être occupées par des essaims sauvages, nous continuerons à former les agriculteurs locaux sur la manière de maintenir les ruches et les colonies en bonne santé, en évaluant la structure des cadres et en vérifiant si les abeilles ont suffisamment de pollen pour produire du miel. Ces connaissances permettront aux agriculteurs d'augmenter leur production agricole, de protéger les cultures contre les éléphants affamés et de compléter leurs revenus grâce à la vente de miel. Le deuxième côté de la clôture était constitué de bandes métalliques, dont le bruit et la vue ont prouvé qu'elles dissuadaient les éléphants de pénétrer dans les champs des agriculteurs. Nous avons installé le troisième côté de la clôture avec des chiffons de piment. Le quatrième côté de la barrière souple était constitué de lumières clignotantes, une technique utilisée avec succès au Botswana.

Facteurs favorables

- Chaque méthode d'atténuation est appliquée et entretenue correctement.

- Après une formation complète à l'apiculture et la mise en place d'un système de surveillance, la clôture des ruches sera entretenue.

- Les colonies d'abeilles ont suffisamment de ressources disponibles pour empêcher les colonies de s'échapper des ruches.

- Intérêt marqué de la part de la communauté. Ceci a été facilité par le succès précédent des unités de réponse rapide dans la dissuasion des attaques de cultures par les éléphants.

- L'accès aux ressources pour maintenir les barrières souples.

- Suivi des incidents de pillage de cultures d'éléphants par le biais de rapports de terrain et de données GPS.

Leçon apprise

Toutes les barrières ont bien résisté, même si deux éléphants munis d'un collier se sont approchés au cours du premier mois. Les 15 et 16 juin, un troupeau de célibataires s'est introduit dans les ruches inoccupées. Ils se sont attaqués aux chiffons de piment, car ils n'avaient pas été rafraîchis comme on le leur avait enseigné. Nous avons communiqué avec le chef, qui comprend maintenant l'importance de la routine de rafraîchissement des chiffons de piment. Il a depuis collecté plus de piment et d'huile de moteur pour les réappliquer. Nous avons demandé à ce que le répulsif à éléphants odorant soit accroché à intervalles réguliers aux clôtures des ruches. La communauté a signalé que les éléphants évitaient les lumières clignotantes. Lors de notre prochain voyage, nous installerons donc des lumières clignotantes à intervalles réguliers jusqu'à ce que l'été apporte une plus grande occupation des ruches. Le transport entre les parcelles et le local de stockage des fournitures est difficile. La distance en ligne droite est de 5 km mais aucun véhicule n'est disponible. Lors de notre prochain voyage, une tour de guet sera érigée plus près des parcelles, dont la base sera transformée en entrepôt. L'employé responsable de Mozambique Wildlife Alliance a également obtenu un permis de conduire afin de pouvoir transporter des fournitures en cas de besoin.

Identifier et mettre en œuvre des cultures alternatives, génératrices de revenus, pour les éléphants non appétissants, en tant que barrières douces aux cultures de subsistance.

On ignore encore beaucoup de choses sur les préférences alimentaires des éléphants et sur les cultures de dissuasion. Afin d'élargir nos connaissances et de créer des méthodologies reproductibles, nous avons étudié les préférences des éléphants à l'égard de 18 types de cultures différentes, dont la plupart ont une valeur économique combinée élevée (nourriture, huile essentielle, valeur médicinale et fourrage pour les abeilles) et peuvent être cultivées sous les climats de l'Afrique australe. Les expériences de type cafétéria nous ont permis d'évaluer plusieurs plantes qui n'avaient jamais été testées en termes d'appétence pour les éléphants. Nos résultats ont montré que des herbes telles que la bourrache et le romarin, aux propriétés respectivement médicinales et aromatiques, étaient fortement évitées, de même que le piment (une culture bien connue pour dissuader les éléphants). Nous avons constaté que la citronnelle et le tournesol, présentés aux éléphants sous forme de plantes fraîches entières, étaient comestibles pour les éléphants. Cela est surprenant, car ces deux types de plantes ont été décrits comme peu appétissants pour les éléphants d'Asie et d'Afrique.

Selon notre système de notation globale, quatre types d'aliments se sont avérés les mieux adaptés à la région du corridor proposé (Bird's Eye Chilli, Cape Gold, Cape Snowbush et Rosemary). Parmi eux, seul le piment rouge avait déjà été testé auparavant. Les trois autres types de plantes ont été utilisés pour la production d'huile essentielle et sont très prometteurs pour la génération de revenus.

Facteurs favorables

- Approbation par les comités d'éthique animale compétents

- Accès à des éléphants (semi-)habitués et respectueux de l'homme

- Accès à des formes fraîches de cultures végétales à tester

- Les expériences doivent être menées par des chercheurs qualifiés, selon un cadre et une méthodologie scientifiquement corrects, soumis à un examen par les pairs avant publication.

- Personnel de soutien et réseau de recherche

Leçon apprise

Les éléphants semi-habitués sont intelligents et pourraient facilement s'ennuyer avec le dispositif expérimental. Le fait que la séquence des types d'aliments soit aléatoire chaque jour a été utile. Nous avons également appris que l'heure de l'expérimentation avait un rôle à jouer. Ainsi, l'après-midi, les éléphants semblaient plus affamés et plus enclins à s'approcher de chaque seau expérimental et à le tester. Le fait de filmer l'ensemble de l'expérience a facilité les analyses, car l'enregistrement des données sur place pouvait devenir compliqué en fonction du comportement de l'éléphant, et la possibilité de revoir la séquence des événements a été utile.

Impacts

Court terme : Stratégies d'atténuation des conflits entre l'homme et l'éléphant (CHE) entraînant une réduction des CHE :

- Donner aux membres de la communauté les moyens de réagir en toute confiance et en toute sécurité aux incidents de pillage des cultures.

- Diminution de l'hostilité des communautés envers les éléphants, réduction du nombre d'éléphants "détruits" par les autorités ou autres.

- Diminution du nombre d'humains et d'éléphants tués par les CHE

- Sauvegarde des moyens de subsistance et de la sécurité alimentaire

À long terme : augmentation des déplacements des éléphants entre les zones protégées (ZP), favorisant la connectivité des écosystèmes :

- Faciliter le transfert des caractéristiques génétiques entre les zones protégées isolées

- Allègement de la pression sur la biodiversité dans les habitats isolés, permettant la reconstitution saisonnière de l'habitat.

- Identification des corridors de faune appropriés, à utiliser pour la planification de l'utilisation des terres, la réduction des taux de déforestation et l'extension de la couverture des aires protégées.

- Amélioration de la situation socio-économique des communautés vivant à l'intérieur ou à proximité du corridor, en réduisant la dépendance à l'égard de ressources naturelles qui s'amenuisent :

- Introduction de cultures alternatives génératrices de revenus pour la diversification des revenus

- Renforcer mutuellement les flux de revenus alternatifs provenant de la production de miel et de la culture de plantes alternatives.

- Élaborer des stratégies touristiques visant à accroître la sécurité financière en faveur des efforts de conservation.

- Promouvoir l'amélioration des compétences des femmes pour en faire des modèles sociaux.

- Renforcement de la communauté : les tours de guet comme centres de transfert de connaissances sur les méthodes d'atténuation, l'agriculture alternative et la génération de revenus.

Bénéficiaires

Communautés rurales vivant à l'intérieur et le long des corridors fauniques

Les populations d'éléphants et d'animaux sauvages qui utilisent les corridors pour migrer entre les zones protégées

Zones protégées dépendant des services écosystémiques et économiques (tourisme) fournis par la faune sauvage en migration

Objectifs de développement durable

Histoire

M. Mkwakwa est le chef d'un village situé dans la vallée de Namaacha, dans le sud du Mozambique. Il cherche désespérément à protéger sa communauté des attaques répétées des éléphants sur les récoltes, en particulier pendant la saison sèche. Il a essayé d'installer des lampes solaires sur de hauts poteaux dans l'espoir de tenir les éléphants à distance. Il a également essayé de construire des murs verts naturels avec des espèces de Comniphora en bordure des cultures. Aucun de ses efforts n'a abouti au degré de protection qu'il souhaitait offrir à sa communauté. Dans le cadre de la stratégie d'atténuation d'Elephants Alive, nous avons séjourné dans un village voisin pour animer un atelier de formation sur les différentes méthodes de protection des cultures par des barrières souples. Des représentants d'Afrique du Sud, de Tanzanie, du Mozambique et du Kenya sont venus partager leur expertise en matière d'érection de clôtures en ruches, de clôtures en bandes métalliques, de clôtures en chiffons de piment et de fabrication de répulsifs pour éléphants et de briques de piment. Le chef et son épouse ont été incroyablement reconnaissants à tant de pays de s'être mobilisés pour tenter de résoudre leurs problèmes. M. Mkwakwa et sa femme ont travaillé sans relâche avec les équipes pour leur montrer, ainsi qu'à sa communauté, à quel point ils appréciaient l'aide et les conseils reçus. Il nous a expliqué à quel point les choses ont été difficiles pour eux et comment les éléphants semblent toujours savoir quand c'est le bon moment pour cultiver le raid, juste avant qu'ils ne soient prêts à récolter. Nous leur avons expliqué que le miel aiderait à polliniser leurs cultures et qu'ils pourraient également tirer un revenu supplémentaire du miel lorsqu'il sera prêt à être récolté pendant les mois d'été. Nous avons mentionné que les abeilles servent d'agents de sécurité pour ses champs, car les éléphants ont peur des abeilles. Nous avons également mentionné que les abeilles ont besoin de suffisamment d'eau. Le chef s'est immédiatement attelé à la construction d'une merveilleuse station d'arrosage pour les abeilles. Nous avons expliqué qu'Elephants Alive reviendrait régulièrement pour former la communauté à la culture de plantes que les éléphants évitent et qui constituent une barrière supplémentaire pour protéger les cultures. M. Mkwakwa et sa femme étaient rayonnants de gratitude et se sont empressés de nous offrir en cadeau d'adieu tout ce qu'ils possédaient, des tissus shweshwe et des racines de manioc. De nouvelles amitiés se sont formées tout au long du voyage pour protéger la sécurité et les biens des gens et les éléphants étaient étrangement au centre de ces ponts qui se formaient entre les communautés et les personnes travaillant au-delà des frontières et suivant les traces des éléphants.