Solutions fondées sur la nature en Mongolie intérieure : La restauration par la conception

The Nature Conservancy s'est associé à des agences gouvernementales et à des partenaires philanthropiques pour restaurer des terres dégradées en Mongolie intérieure, en s'appuyant sur une approche de restauration par conception pour identifier des solutions basées sur la nature (NbS) ayant un impact maximal, pour renforcer la résilience face au changement climatique et pour renforcer les moyens de subsistance et le bien-être de la communauté. Cette approche de "restauration par conception" a été mise en œuvre pour la première fois dans le comté de Helinge'er en 2010, un écotone agro-pastoral typique du centre de la Mongolie intérieure. Pendant 10 ans, TNC et ses partenaires ont mis en œuvre des approches innovantes, telles que l'échange de puits de carbone, les applications météorologiques pour la gestion des prairies et les techniques d'"agriculture sèche" pour la gestion durable des terres agricoles, qui sont toutes devenues des pratiques courantes pour la population locale d'Helinge'er. Les activités de RbD ont permis de restaurer les écosystèmes, de réduire l'impact des tempêtes de sable et d'utiliser plus efficacement les ressources naturelles dans l'agriculture, entre autres avantages. TNC promeut à présent la RbD dans des régions plus vastes de Mongolie intérieure, avec trois autres sites de projet en cours de réalisation.

Contexte

Défis à relever

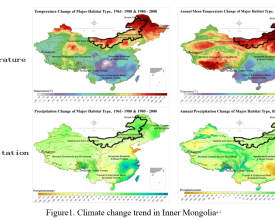

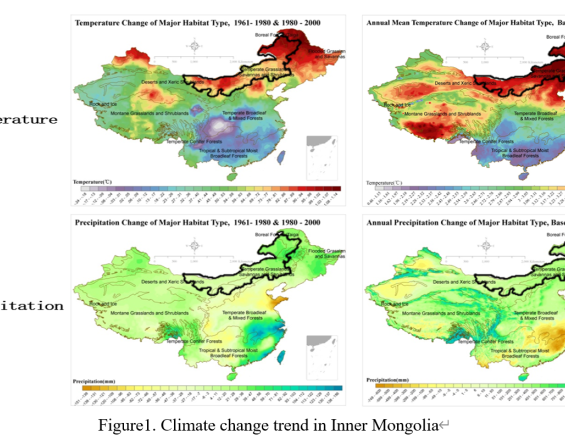

Sur une longue période, l'utilisation non durable des terres (surpâturage, mise en valeur et culture inappropriées des terres, exploitation forestière excessive et utilisation excessive des ressources en eau) et le changement climatique ont endommagé l'écologie fragile de la Mongolie intérieure, entraînant la dégradation des terres et la perte de la fonction des services écosystémiques. En outre, le changement climatique intensifie encore l'impact des activités humaines. Les données et observations historiques ainsi que les simulations futures ont prédit une tendance à la sécheresse et au réchauffement dans l'est et le centre de la Mongolie intérieure. Les conséquences alarmantes de la pénurie d'eau et de la désertification constitueront une menace immédiate pour l'écologie et la production locales, ainsi que pour les moyens de subsistance de la population.

Emplacement

Traiter

Résumé du processus

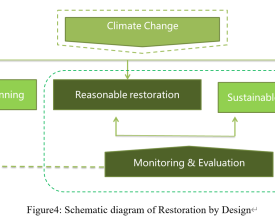

La restauration par conception (RbD) est une approche de la conservation qui permet à des équipes multidisciplinaires a) d'identifier les zones à haut rendement pour la biodiversité, la séquestration du carbone et la restauration écologique b) d'appliquer des NbS ciblées qui bénéficieront à la fois à la nature et aux communautés locales et c) d'aider les zones à atténuer les effets du changement climatique et à s'y adapter. Il est essentiel que ces éléments constitutifs prennent en compte les intérêts et les risques des communautés locales à tous les niveaux afin d'instaurer la confiance et d'aider les communautés locales à construire un avenir résilient au changement climatique sur leur territoire. La RbD est une approche qui peut être appliquée par tout défenseur de l'environnement travaillant en partenariat avec les communautés locales, les ONG, les groupes gouvernementaux et les organisations de la société civile.

Ces cinq éléments sont interactifs et itératifs - et nous continuons à apprendre de chacune de ces étapes et à appliquer les résultats tout au long du cycle de vie du projet.

Blocs de construction

Planification scientifique (restauration écologique et planification de la conservation pour l'adaptation au changement climatique)

Dans le comté de Helinge'er, la planification systématique de la conservation (SCP) a été utilisée pour planifier la restauration et la protection écologiques du comté en tenant compte des prévisions de changement climatique. Tout d'abord, les demandes de services écosystémiques régionaux ont été déterminées en fonction du zonage national des fonctions écologiques et des lignes rouges écologiques. Deuxièmement, pour s'assurer que les principaux types d'écosystèmes dans chaque parcelle de fonction écologique peuvent assurer des fonctions de service écologique durables et fiables, l'état historique et actuel de chaque parcelle de fonction écologique a été évalué à l'aide d'analyses documentaires et d'enquêtes sur le terrain (enquêtes communautaires), et les tendances de l'écosystème ont été prédites en fonction de différents scénarios de changement climatique. La sensibilisation des communautés a été cruciale pour comprendre comment l'expérience vécue par les agriculteurs et les éleveurs se comparait à la littérature scientifique et a permis d'instaurer un climat de confiance avec les communautés.

Les objectifs de la zone de protection ont été fixés et le degré d'influence humaine dans la zone a été pris en compte. Enfin, pour les zones à fonction écologique importante, l'état actuel de l'écosystème a été comparé aux principaux types d'écosystèmes qui peuvent continuer à jouer leur rôle. S'ils étaient cohérents, ils ont été identifiés comme zones protégées. Les incohérences ont donné lieu à des zones de restauration, et le type d'écosystème cible pour la restauration a alors pu être déterminé.

Facteurs favorables

- Le partenariat de TNC avec le Bureau des forêts et des prairies de Mongolie intérieure a permis de faciliter les enquêtes de terrain avec la communauté.

- La population plus âgée d'Helinge'er se souvient d'une époque où les services écologiques fonctionnaient très bien et est impatiente de voir les écosystèmes restaurés.

- Des partenariats avec des donateurs philanthropiques, tels que la Fondation Lao Niu, ont rendu ce travail possible. Le travail de RbD et d'engagement communautaire prend du temps, et il est utile d'avoir des bailleurs de fonds qui comprennent et investissent sur des périodes plus longues.

Leçon apprise

Lorsque TNC a commencé à travailler à Helinge'er, il n'existait pas d'approche de planification scientifique systématique pour cet écosystème particulier, ses facteurs de dégradation et les besoins de la communauté. La CPD est une approche globale, et nos équipes n'avaient pas encore réalisé ce niveau de planification dans les écosystèmes arides et semi-arides de Mongolie intérieure.

Nous avons réalisé qu'il était vital de s'engager avec les communautés locales et de développer des relations de collaboration avec les experts locaux pour mettre en place un projet de restauration à long terme.

Grâce à des études approfondies sur le terrain, nous avons pu combiner les modèles scientifiques existants avec l'expertise locale et les connaissances des communautés. Cette approche hybride nous a permis de nous adapter aux besoins spécifiques de la région et de ses habitants.

Restauration écologique (solutions basées sur la nature qui restaurent les écosystèmes et séquestrent le carbone, par exemple l'approche "arbres, arbustes et herbe")

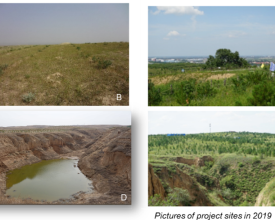

Afin de restaurer les terres dégradées, d'accroître la couverture végétale et la biodiversité, et de rétablir les fonctions écosystémiques de brise-vent et de fixation du sable, le projet utilise la structure tertiaire "arbres, arbustes et herbe". Les espèces indigènes d'arbres, d'arbustes et d'herbes ont été sélectionnées pour leur fonction de service écologique maximale, y compris la séquestration du carbone et le potentiel d'habitat. Depuis 2010, nous avons restauré une zone prioritaire de 2 585 hectares de terres dégradées, telle qu'identifiée par le plan de restauration écologique du comté d'Helinge'er. Les activités de restauration comprennent la plantation de près de 3 millions d'arbres qui, selon les estimations, captureront plus de 160 000 tonnes de CO2 au cours des 30 prochaines années.

Visant les zones de ravinement où l'érosion du sol et de l'eau est importante, le projet a intégré des approches techniques et biologiques et a introduit de nouvelles technologies telles que la "couverture biologique" (il s'agit d'un outil écologique de protection des pentes très résistant, composé de divers matériaux naturellement dégradables). La couverture biologique contribue à réduire l'érosion du sol sur la pente) et a permis de restaurer avec succès près de 600 hectares (9 000 mu) de sol et de zones de perte d'eau dans 14 ravins.

Facteurs favorables

- L'adhésion et l'accord de toutes les parties - le Bureau forestier de Mongolie intérieure, la communauté locale, les scientifiques de TNC et les bailleurs de fonds - ont permis une collaboration efficace pendant une décennie pour mettre en œuvre les activités de restauration.

- Des partenariats avec l'entreprise chargée de la mise en œuvre pour s'assurer que le processus de restauration se déroule comme prévu.

- Grâce à un soutien philanthropique, TNC a pu embaucher des travailleurs temporaires et saisonniers pour mettre en œuvre les travaux de restauration et fournir un revenu supplémentaire indispensable à la population qui vivait au niveau du seuil de pauvreté ou à proximité.

Leçon apprise

Par le biais de simulations et de calculs, les zones les plus importantes pouvant garantir la restauration de la fonction de service écologique ont été sélectionnées selon le principe d'une zone aussi petite que possible et de coûts d'entretien aussi bas que possible. Le coût est l'un des principaux obstacles à la restauration écologique et peut empêcher les communautés locales d'y participer. Au cours de la mise en œuvre, la méthode est constamment ajustée en fonction de la situation réelle et afin de réduire les coûts (main-d'œuvre, transport, etc.) et d'améliorer l'efficacité. Lorsque le coût économique est plus faible, la méthode devient plus évolutive/adoptable par d'autres.

Gestion durable des terres (outils décisionnels accessibles et fondés sur la technologie ; gestion durable des pâturages dans les prairies dégradées ; gestion durable de l'agriculture "sèche" adaptée aux zones arides et semi-arides)

En coopération avec l'université agricole de Mongolie intérieure, le projet a mis en œuvre une "gestion intelligente des prairies" sur 200 hectares (3 000 mu) de prairies dans le comté de Helinge'er, en combinaison avec le suivi de la croissance de la végétation et l'utilisation des données météorologiques pour déterminer le bon moment pour commencer le pâturage de printemps. Les éleveurs ont pu déterminer de manière dynamique la durée et l'intensité du pâturage, et adapter le plan de pâturage en équilibrant l'herbe et le bétail. Après trois années de travaux pilotes, le projet a permis de mettre au point le modèle "pâturage pendant les saisons chaudes et alimentation pendant les saisons froides", adapté à la zone locale et à d'autres sites présentant des conditions similaires dans les prairies du nord de la Chine.

Le projet a aidé les agriculteurs locaux à mieux faire face à la pénurie d'eau qui s'accélère, exacerbée par le changement climatique. Les agriculteurs ont adopté les technologies et pratiques intégrées de l'agriculture sèche à haut rendement, de l'agriculture sèche écologique et de la fertilisation à l'aide de la formule d'analyse des sols, des variétés de cultures sélectionnées résistantes à la sécheresse, un paillage amélioré et une irrigation innovante pour utiliser pleinement les précipitations naturelles. Cette approche, qui combine des outils de données accessibles et de nouvelles pratiques de gestion des terres, a permis d'obtenir de multiples avantages en termes d'efficacité de l'eau et des engrais, ainsi qu'une augmentation de la production et des revenus.

Facteurs favorables

- La collaboration avec l'université agricole de Mongolie intérieure et les communautés locales a permis d'adapter nos approches aux besoins et aux conditions locales.

- L'utilisation répandue des smartphones dans les zones rurales rend l'application Smart Grasslands facilement accessible.

- Un engagement actif auprès des agriculteurs qui nous soutiennent et qui jouent ensuite le rôle d'ambassadeurs pour défendre la méthode.

Leçon apprise

Nous avons pu développer une collaboration étroite avec les communautés locales en prenant le temps de comprendre les difficultés qu'elles rencontraient avec les techniques existantes d'agriculture et d'élevage. Nous avons ciblé les membres de la communauté qui exprimaient leur mécontentement à l'égard du statu quo et qui espéraient changer les méthodes de production. Grâce à cette collaboration et à la valorisation explicite des connaissances traditionnelles de la communauté locale, nos nouvelles méthodes scientifiques de gestion durable étaient mieux adaptées à la région et plus susceptibles d'être adoptées à grande échelle. Par exemple : la détection de la période d'alimentation (saisons froides) qui convient à leurs pratiques traditionnelles, la sélection de variétés de cultures résistantes à la sécheresse en apprenant quelles cultures n'étaient plus plantées en raison du manque d'eau.

Développement communautaire (sensibilisation à l'environnement, possibilités de bénévolat et formation professionnelle)

Éducation à l'environnement : des ateliers d'éducation à l'environnement ont permis de sensibiliser les membres de la communauté à l'environnement et de les aider à mieux comprendre l'équilibre entre l'écologie et le développement.

Possibilités de volontariat : la promotion de l'agriculture sèche a amené des milliers d'agriculteurs des communautés environnantes à participer au projet, à s'engager tout au long du processus de plantation d'essai, d'adaptation et d'ajustement selon les besoins, et de récolte. Ils n'ont pas eu besoin de tester les effets dans leurs propres champs.

Formation professionnelle : amélioration de la capacité de la communauté à appliquer de nouvelles technologies et de nouveaux modèles aux méthodes d'agriculture et d'élevage. Elles ont aidé la communauté à mettre en place de nouvelles coopératives.

Facteurs favorables

- Le conseil de village local a apporté un soutien important qui a permis aux agriculteurs locaux de participer aux ateliers et aux sessions de formation.

- Les ateliers et les formations se déroulant dans les villages et à des heures qui conviennent à toute la famille, un plus grand nombre d'agriculteurs ont pu y participer, sans avoir à se déplacer.

- La campagne d'élimination de la pauvreté menée par le gouvernement a contribué à sensibiliser la communauté au fait qu'une formation professionnelle permettrait d'améliorer les revenus - et donc à la rendre plus disposée à apprendre.

Leçon apprise

L'effort de restauration écologique ne peut être maintenu que si les communautés locales comprennent la relation entre une bonne écologie et leur vie quotidienne, en particulier lorsque la production quotidienne comprend la gestion des terres par le biais de l'agriculture et de l'élevage. L'amélioration de la conscience environnementale de la communauté et le renforcement des compétences en matière d'agriculture durable, tout en respectant leur culture et en valorisant leurs connaissances sur le terrain, ont permis à l'homme et à la nature de prospérer ensemble.

Suivi et évaluation (suivi écologique et évaluation des avantages)

Surveillance écologique : Le projet surveille en permanence et évalue régulièrement la restauration de la végétation et ajuste les mesures de gestion de la végétation en temps opportun en fonction des changements dans la croissance de la végétation, de l'humidité du sol et d'autres indicateurs en employant des personnes locales comme travailleurs saisonniers.

Évaluation des avantages : Aider les habitants de la communauté à améliorer leurs revenus de 2 000 yuans en moyenne par ménage ayant adopté les nouvelles techniques, permettant ainsi aux agriculteurs de bénéficier directement des résultats de la restauration écologique.

Facteurs favorables

- Accès à la communication avec les agriculteurs locaux à un stade précoce.

- L'expertise locale et les travailleurs saisonniers issus des communautés locales ont permis de suivre les progrès de la restauration écologique

- Les conseils de village locaux et les agriculteurs qui ont participé à nos enquêtes communautaires ont contribué à l'évaluation des avantages sociaux et économiques.

Leçon apprise

Nous avons replanté d'autres arbres dont certains n'avaient pas poussé correctement après la première série de plantations. Mais après avoir effectué des contrôles et des tests, nous nous sommes rendu compte qu'il n'y avait pas assez d'humidité pour permettre la plantation de cette quantité d'arbres. Nous avons ajusté les plans de replantation, soit en ne plantant pas davantage, soit en réduisant la densité de replantation. Nous avons planté différentes espèces d'arbres indigènes dans la zone à une seule espèce d'arbre afin d'accroître la biodiversité et la résistance au changement climatique.

Impacts

Avantages pour l'environnement :

- Le taux de préservation du boisement a été maintenu à plus de 85 %.

- La couverture végétale du sous-bois a augmenté de plus de 60 %.

- La productivité des prairies par unité de surface a augmenté de 60 à 94 %.

- La diversité végétale est passée d'environ 40 à 80 espèces, ce qui est significatif pour les zones arides et semi-arides.

- La santé des sols s'est considérablement améliorée

- La zone de démonstration absorbe 5 463 tonnes de CO2 par an, fixe 25 000 tonnes de sol et contrôle l'érosion des sols.

Avantages sociaux et économiques :

Helinge'er est au centre des efforts de réduction de la pauvreté menés par le gouvernement. De nombreuses personnes vivent en dessous ou à proximité du seuil de pauvreté, en particulier sur le site du projet.

- 18 emplois à long terme

- Travail à court terme et saisonnier : 1,14 million de jours de travail pour plus de 10 000 personnes (2 690 ménages ruraux) ayant historiquement peu d'accès à des revenus supplémentaires.

- Des milliers d'agriculteurs des communautés voisines ont amélioré le revenu de leur ménage de 2 000 yuans (~ 308 USD) par an après avoir adopté nos nouvelles techniques, soit une augmentation d'environ 20 %.

Climat, communauté et biodiversité

TNC s'est associé à The Walt Disney Company pour l'échange de puits de carbone forestier sur le marché volontaire international du carbone. Les 3 millions d'arbres plantés devraient permettre de capturer plus de 160 000 tonnes de carbone au cours des 30 prochaines années, et le projet, le premier en Mongolie intérieure, a reçu la certification CCB de niveau or de l'Alliance pour le climat, la communauté et la biodiversité (CCBA).

Bénéficiaires

Agriculteurs et éleveurs locaux : amélioration de la santé des sols ; utilisation plus efficace des ressources ; résilience au changement climatique

Communauté : fierté et lien avec la terre restaurée ; écotourisme/destination éducative ; réduction de l'impact des tempêtes de sable

Gouvernement : motivation pour conserver la nature

Objectifs de développement durable

Histoire

La pandémie de COVID-19 a bouleversé nos univers et nos habitudes quotidiennes. En raison des mesures de confinement, de nombreuses personnes - en particulier les étudiants universitaires, les travailleurs migrants et saisonniers et les personnes sous-employées - ont été contraintes de retourner dans leur ville d'origine pendant une longue période. Il en a été de même en Mongolie intérieure et dans les communautés environnantes de Helinge'er, où TNC mène des travaux de conservation dans le cadre du programme Restoration by Design.

Helinge'er a toujours connu un taux de pauvreté élevé, obligeant de nombreuses personnes à partir pendant de longues périodes pour chercher du travail et de l'éducation. Avec la mise en place des restrictions COVID, de nombreux membres de la communauté découvraient pour la première fois les avantages d'un effort de conservation de dix ans. Ils passaient plus de temps à l'extérieur et ont pu constater que les terres arides se sont transformées en couches de verdure, avec une augmentation des observations d'animaux sauvages tels que les renards roux, les lapins, les faisans, les chevreuils et les cerfs. Les tempêtes de poussière qui obscurcissaient le ciel au printemps et provoquaient une gêne physique pour les gens ont maintenant disparu.

La découverte du potentiel de régénération de l'écosystème et des solutions fondées sur la nature a permis de renouer avec cet écosystème. Les jeunes se sentent désormais liés à leur terre, à leur héritage et à leur culture comme jamais auparavant, et ils commencent à entrevoir un avenir pour leur vie sur leur terre natale.

Le travail de TNC Inner Mongolia s'est avéré fructueux parce qu'il prend en compte les expériences des populations locales dès les premières étapes de la planification. Nos enquêtes sur le terrain et auprès des communautés ont renforcé ce que nous avions appris à travers la littérature et les études scientifiques : les impacts climatiques ne sont pas seulement ressentis par la terre, mais aussi par les personnes qui y vivent. Nous avons appris quels étaient les défis auxquels les agriculteurs, les éleveurs et les membres des communautés étaient confrontés en raison de la dégradation de l'environnement et nous les avons aidés à voir comment la NbS pouvait atténuer ces problèmes.

Aujourd'hui, les gens visitent Helinge'er pour constater les améliorations spectaculaires de la terre, qui contrastent fortement avec les systèmes dégradés voisins qui n'ont pas fait l'objet de travaux de conservation.