Establishment of a financially sustainable model of private MPA management through ecotourism

This solution addresses governance of protected areas, overexploitation of natural resources and lack of environmental awareness which are the main threats to biodiversity conservation and sustainable fisheries in Zanzibar. CHICOP has developed a financially sustainable model of private MPA establishment and management through eco-tourism which benefits local communities by promoting food security, sustainable fisheries, alternative livelihoods and implementing environmental education programs.

Context

Challenges addressed

With rapid population growth and the advent of mass tourism in Zanzibar, coral reefs are under pressure from overfishing, poaching and illegal fishing methods, a situation not uncommon for developing countries in the tropics. Insufficient capacity for effective marine governance and enforcement, poverty, and lack of alternative livelihoods make it difficult to balance a sustainable environment and community. Overexploited natural resources, a lack of environmental awareness and a poor marine governance are the main challenges.

Location

Process

Summary of the process

The business model (building block 1) showcases the innovation and creativity of this project and manifests the model of having revenue generated from ecotourism which is reinvested in MPA management and environmental education programs. Community engagement, involvement and the maximization of benefit streaming (building block 2) are foundational to the projects' overall success, and clear and transparent communications are at the heart of this. Scientific knowledge is maximized (building block 3) to guide and better inform MPA decision making, and has been successfully incorporated into the MPA management approach. To create awareness on the value of coral reefs, environmental education is provided to wide sectors of society (building block 4) making tourists partners in conservation. Effective management and enforcement (building block 5) are essential to ensure a well-functioning MPA, and have been key for the success of the project. The tourism component (building block 6) is vital to the sustainability of the MPA and as a learning center tourism operations must be environmentally sensitive. The eco-architecture and technology provides a best-practice model for marine and coastal eco-tourism operations around the world.

Building Blocks

Ecotourism as a model for a private, not-for-profit MPA

From 1991-1994 Chumbe Island Coral Park Limited (CHICOP) successfully negotiated with the semi-autonomous government of Zanzibar, Tanzania for the western coral reef and forest of Chumbe Island to be gazetted as an MPA, with management of the MPA entrusted to CHICOP. The company was specifically established for the purpose of developing and managing the MPA financially self-sustainably, utilizing ecotourism to generate revenue for all MPA operational costs and associated conservation, research and education activities. Through this Chumbe became the first managed marine park in Tanzania, the first privately managed MPA in the world, and to date is one of the only financially self-sustainable MPAs globally. The company objectives are not-for-profit, implementing conservation and education initiatives over more than 20 years under the framework of two management plan iterations that were developed with wide stakeholder participation (1995-2005 and 2006-2016). Ecotourism business operations follow commercial principles for maximizing revenue and promoting cost-effectiveness to ensure a sustainable revenue stream for MPA activities, exemplifying a successful business-oriented approach to sustainable and effective MPA management.

Enabling factors

- Adoption of a liberalization policy allowing foreign investment back into the country, in particular in the tourism sector

- Investment Protection Act passed in 1989, and the Zanzibar Investment Agency established in 1991 to screen investment proposals

- Investor's commitment, determination, project management experiences in Tanzania and private capital to launch the initiative

- Availability of professional & committed volunteers

- Availability of donor funds for non-commercial project components

Lesson learned

- Private management of an MPA can be effective and economically viable, even in a challenging political environment

- There is a clear market in the tourism industry for state-of-the-art eco-destinations that support strict conservation and sustainability principles

- No need for compromise! Private management has strong incentives to achieve tangible on-ground conservation goals, co-operate with local resource users, generate income, be cost-effective and keep overheads down

- Investment in conservation, environmental technologies & the employment of operational staff for park management and education programs, raises costs considerably, making it more difficult to compete with other tourist destinations. Favorable tax treatment could encourage such investments, but is not granted in Tanzania

- Investment security is limited by land tenure being available only through leasehold, while land leases can be revoked by the State with relative ease, thus weakening long-term security of tenure

Community involvement and benefits

Sustainable park management often means that access to traditional resources is restricted or modified for sustainable management. Such impacts therefore need to be offset by ensuring local communities and resource users directly or indirectly benefit from the MPA and are fully involved in the solution. Chumbe MPA was established through participative partnerships with local communities, and included: village meetings before and during project development; employment and training of community members for various project roles, including former fishermen as park rangers; village leader involvement in management plans and Advisory Committee meetings; and the provision of wider income opportunities for local communities (such as agricultural products for the restaurant, building materials and handicrafts, outsourcing road and boat transport and craftsmen services during maintenance). Additionally the project benefits local communities through the protection of valuable biodiversity; restocking of depleted fisheries and degraded coral reefs; promotion of environmental awareness among fishers, and provision of emergency services to local fishers in distress in the absence of a marine rescue service in Tanzania.

Enabling factors

Local communities have been involved throughout the project development, ensuring bottom-up engagement. The project has sustained clear and positive communications at all times, encouraged communities to actively engage in meetings, respected cultural traditions, and has maintained a high level of accountability and transparency in all aspects of its operations. The strategy of providing opportunities for those who want to take them, rather than making promises, has been key to the success.

Lesson learned

Biannual Advisory Committee meetings attended by leaders from neighboring villages have proven to be an important communication tool to discuss management objectives, project progress and other emerging issues. Outside these formal meetings, CHICOP has built up trust with local communities through consistent local informal meetings and dialogue, and has also learned from some mistakes - such as an inconsistent communication of MPA borders in the early years of establishment, which led to temporal confusion, anger and mistrust amongst local fishers. Since awareness of the importance of coral reefs was limited in the early years of the project, and the MPA approach of a ‘no take zone’ was such a new concept, CHICOP has also had to actively demonstrate how the MPA project links to peoples’ daily lives. The religion and culture of these societies touches all aspects of daily life, hence, the project also works closely to negotiate, explore and find compromises in times of any dispute.

Resources

Science-based decision making and capacity building

Establishment and management of the MPA has been built upon a strong biophysical and social science foundation; from preliminary baseline surveys at all levels at the start of conceptual development, through to regular monitoring and assessment to ensure an adaptive management approach. Since 1993 CHICOP has employed professional expatriate marine biologists as Conservation Coordinators, for training park rangers and overseeing all research and monitoring programs. Extensive and cross-institutional capacity building efforts have also been provided on a range of projects both within Chumbe MPA and with partner institutions and emerging coastal conservation programs across the region. CHICOP’s ranger team has captured daily monitoring and observational data in the MPA, leading to Chumbe having the most extensive monitoring data set of any MPA in Africa, possibly the world, spanning more than 20 years of operations. Results are used for decision making and are shared through a range of information materials such as scientific publications, status reports and newsletters. Furthermore, all CHICOP staff are trained in the basics of reef and forest ecology, English language skills, ecotourism and waste management practises.

Enabling factors

- Ongoing capacity building of MPA staff and the availability of resources (boats, fuel, equipment) to effectively conduct monitoring are crucial.

- Partnerships with local and regional organizations are vital for facilitating wider training opportunities.

- Adequate assessment methodologies enable systematic data gathering and decision making.

- Adaptive management approaches ensure that monitoring results are assessed towards objectives and programs are adapted according to evolving knowledge.

Lesson learned

- Social and ecological monitoring enables a thorough understanding of the impacts of activities in the MPA, and the potential scales and frequencies of challenges and opportunities as they arise.

- Effectiveness of MPA management can only be assessed if long-term monitoring data is in place that provides temporal evidence of whether management objectives are being fulfilled.

- Science-based adaptive management is a very dynamic, "learning-by doing" process which requires commitment from everybody involved.

- As monitoring is conducted by expertly trained Chumbe staff, it increases their environmental awareness and provides a sense of ownership and motivation to protect the monitored habitats.

- Since CHICOP employs people from nearby communities, who have limited formal education and skills prior to joining Chumbe, much on-the-job training has been provided, requiring considerable time and investment.

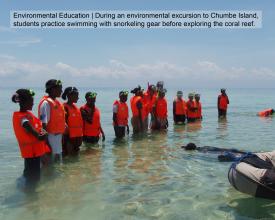

Multi-level environmental education and outreach programs

Public communication, education and awareness-raising on the importance and vulnerability of the marine ecosystem is a key building block for CHICOP which offers environmental education for fishers, students, teachers, government officials, tourism operators and visitors. CHICOP implements ‘Education for Sustainable Development’ through an ‘Environmental Education program’ which since 1995 has welcomed more than 6400 schoolchildren, 1100 teachers and 690 community members for one-day field excursions to Chumbe Island. The excursions offer hands-on activities, discussions in the Island’s own classroom using interactive learning tools, and special floatation devices make it possible for everyone to participate in snorkeling which is especially unique for the Muslim girls and women in the region, who rarely learn how to swim. In collaboration with the Ministry of Education, CHICOP has incorporated a coral reef module into the local school curricula and conducts teacher training related to environmental sustainability aimed at assisting in the establishment of environment clubs in schools and communities across Zanzibar. These clubs address issues such as waste management, biodiversity loss and climate change mitigation projects.

Enabling factors

- Access: close proximity of Chumbe Island to Zanzibar.

- Fringing reef on the western side of the island is suitable for educational programs.

- Since all local field excursions, workshops and associated educational activities are provided free of charge at the expense of CHICOP, revenue generated from eco-tourism fully funds the Environmental Education programs.

- Trust and good relationships with local institutions (such as schools and the Ministry of Education) and multi-level learners.

Lesson learned

Establishing the education program from the very start of operations on Chumbe has proven critical for both the success of the education initiatives and the MPA more generally. From the moment the MPA was established, and even prior to the tourism infrastructure being completed and revenue generating operations commencing, schools programs began, supported by private funds and small scale grants. This enabled a wide cross-section of society (school children, teachers, fishers groups etc.) to visit and learn on Chumbe, gaining awareness on both the importance and role of the marine environment in their everyday lives, and the importance of MPAs and the ecosystem services being supported by Chumbe’s protected habitats. Implementing systematic safety protocols for all activities provides security for individuals to try new activities and learn new information. Curriculum support to the Education Ministry has provided Zanzibari children with a fresh appreciation of the marine environment.

MPA management and enforcement

Following the gazettement of the Chumbe MPA in 1994 by the Government of Zanzibar, management was entrusted to CHICOP for a renewable 10 year period for the Reef Sanctuary (now in its third renewal period). The Management Plans define objectives, activities, research regulations and Do’s and Don’ts both for visitors and staff. Only non-consumptive and non-exploitative activities are permitted. Research is limited to non-extractive studies, and fishing and non-authorized anchoring in the MPA are prohibited. Scuba diving is only permitted for researchers and documentary film crews. In order to increase enforcement capacity, rangers receive on-going training in surveillance techniques and processes for promoting and ensuring MPA compliance. Patrols are done by boat, on foot and from the top of the lighthouse. The rangers are unarmed and rely on persuading fishers and building awareness. Compiled daily monitoring reports are shared with the Department of Fisheries Development in Zanzibar. Visitor numbers per day are restricted and only boats arranged by Chumbe can bring visitors to the MPA. Demarcation buoys are deployed along the MPA boundaries and compliance levels are high with positive relations with local fishers.

Enabling factors

- Legal framework enabled the establishment of a management agreement between government and CHICOP

- Employment of former fishers trained on the job and provided with capacity building opportunities, involvement of wide ranging stakeholders and implementation of environment education, has built positive relations with local communities

- Small size of the MPA enables effective patrolling

- Long-term financing ensures effective enforcement through provision of equipment and full-time trained rangers.

Lesson learned

Chumbe has been recognized as an effectively managed MPA based on a range of biophysical, social and governance criteria. Key to effective management has been the continuous assessment of activities against MPA goals, and timely responsiveness to challenges through adaptive management. Chumbe’s remoteness, relatively small size and the committed work of the rangers has supported effective enforcement and poaching incidents remain low. Key factors for success are:

- Daily patrols, surveillance and presence of rangers on the island 24/7.

- Specialist ranger training on how to approach and engage fishers positively, for productive dialogue to inform, inspire and promote willing compliance, rather than deploying classic confrontational, rejectionist enforcement approaches.

- Daily record keeping to assess trends and explore causal factors for infringements (such as weather patterns or special festival periods) to implement culturally acceptable and practicable mitigating measures.

Resources

Eco-architecture and eco-operations

To effectively ensure that tourism operations within the MPA do not damage the surrounding ecosystem, CHICOP has, from its outset, been committed to ecologically sustainable operations and infrastructure. All buildings on the island (7 visitor bungalows, a visitor center and staff quarters) have a rainwater catchment system for shower and tap water, heated by solar power; a vegetative greywater filtration system for wastewater management; photovoltaic power generation and composting toilets. Air-conditioners and other coolants are not required due to the bungalows being positioned to channel winds in line with the predominant seasonal wind directions. Organic waste is composted and reused in the composting toilets. Non-organic waste items are reduced at source (non-acquisition of plastic bags / use of re-fillable containers etc.), and any waste products that are re-useable (such as jars, bottles) are used in-house or decorated and sold as handicrafts. The few remaining waste products are removed from the island. Guests use solar torches at night to avoid light pollution, and all buildings are set-back from the beach, situated at least 4 meters above high-tide mark to avoid potential damage from storm surges and coastal erosion.

Enabling factors

- Eco-technologies emerging onto the market when Chumbe was getting established, and support for importing advanced technological items (photovoltaic panels).

- Eco-architecture as a new field - the willingness of an expert who conceived the Chumbe design combined with the openness of Chumbe to experiment with new architecture, resulted in the Chumbe eco-lodge.

- The efforts of the local artisans and builders to embrace and learn new concepts and skills.

- Learning & adapting along the way.

Lesson learned

Most systems have worked well throughout, however, the following challenges were encountered:

- Eco-technologies were not only unknown to local builders, but there was also little experience available on their functioning under tropical island conditions, requiring creative solutions-based approaches to maintenance issues over time.

- From 1994-1997 Zanzibar suffered an energy crisis that created shortages of fuel and cement on the local market. This complicated the building process and contributed to enormous delays. Building operations lasted altogether over four years instead of the one-year originally planned. As a consequence, investment costs soared and the price structure had to be adjusted to aim more upmarket.

- Some technologies, in particular photovoltaics and greywater vegetative filtration were challenging to operate and maintain and have needed several interventions by experts.

Impacts

As the first financially self-sustaining MPA in Africa, CHICOP’s model of MPA management and ecotourism is a leading example for marine and coastal practitioners, tourism developers, investors and managers around the world. Shared experiences and lessons learned have helped develop policies for nature conservation and investment that encourage similar initiatives. CHICOP demonstrates ecological, economic and social impacts including:

- Helping to restock depleted fisheries through the “spill-over effect” of fish from the protected Chumbe reef into adjacent, degraded fishing grounds, impacting long-term subsistence and livelihoods of local communities.

- Implementing ecologically sustainable architecture and operations that have close to zero impact on the sensitive terrestrial and marine ecology of the island, while promoting social resilience through the employment of 42 local people (each with an average of 12 dependents), access to sponsored education, long term loans, and creation of markets for local products and handicrafts.

- Pioneering environmental education in Zanzibar through financing and implementing field excursions to Chumbe for thousands of school children, teachers, community members and government officials.

Beneficiaries

- Local communities dominated by artisanal fishers & female shell collectors

- Zanzibari students & teachers

- Government officials

- International students

- Tanzanian employees, producers & traders of food and handicraft

- National & international tourists

Sustainable Development Goals

Story

After working in development aid nearly 2 decades Sibylle Riedmiller felt disillusioned by the failure of most aid projects and was particularly frustrated by the rampant destruction of coral reefs and poor marine governance in Tanzania that had no marine protected areas at the time, nor any legal provisions for marine conservation. Coral reefs were not covered in school syllabi and there was little awareness about marine issues among Zanzibari people. In 1990 Zanzibar started inviting foreign investment into tourism. Sibylle saw an opportunity to establish a privately managed marine conservation area to be used for environmental education funded by eco-tourism. Chumbe Island – at the time an uninhabited island - was an appropriate site for exploration. Host to a coral reef of exceptional biodiversity and beauty, research revealed that fishing had traditionally not been allowed on its western side, due to concerns of small boats obstructing the shipping channel to Dar es Salaam. But all of this was changing – fishers were going farther distances due to diminishing catches, making conservation and fisheries management ever more pressing. Therefore it was timely to establish an MPA whilst no traditional users were to be displaced, and to base management on co-operation with local fishermen. In 1990, Sibylle started campaigning and presented a business plan to establish Chumbe as a privately managed MPA financed through ecotourism, with the condition that the Government of Zanzibar (GoZ) declared the fringing coral reef and island forest as protected areas. This required lengthy negotiations with seven GoZ departments. Finally in 1993, GoZ approved and gazetted the Chumbe Reef Sanctuary and Forest Reserve in 1994 and 1995. Sibylle registered Chumbe Island Coral Park Ltd. (CHICOP) and signed agreements with GoZ to confer full management of the protected area to CHICOP. It took another 4 years to develop the ecotourism infrastructure using state of the art eco-architecture and technology, recruit experts and local staff, provide training, undertake outreach with local communities and establish the conservation and education programs on the island until Chumbe could finally open to visitors in 1998. Since this time we have succeeded in developing Chumbe into a fully ecologically and socially sustainable MPA providing high-quality services to visitors while conserving biodiversity and promoting environmental awareness – all entirely financially sustainably.