Determinación de prioridades para la restauración del paisaje forestal a partir de la cartografía participativa y los inventarios forestales a nivel subnacional - Togo

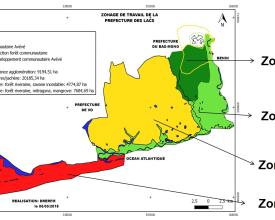

Los paisajes forestales y los beneficios que proporcionan -por ejemplo, madera, leña, regulación del agua, protección del suelo y regulación del clima- son cruciales para el bienestar de la población de Togo. Sin embargo, muchos paisajes están degradados debido al uso insostenible de los recursos. Es crucial mejorar sus condiciones, a través de la restauración, para mejorar la seguridad alimentaria y el acceso al agua. Esta solución define opciones concretas para la restauración del paisaje forestal (FLR) y la planificación del uso de la tierra basadas en la cartografía participativa y en inventarios de recursos forestales a nivel subnacional que abarcan 410.000 ha. Proporciona la base para la gestión sostenible de ecosistemas agrarios, forestales y de manglares con diferentes sistemas de tenencia de la tierra, como bosques sagrados, comunitarios y familiares y áreas protegidas, contribuyendo al bienestar de la población local, la adaptación al cambio climático y la conservación de la biodiversidad.

Contexto

Défis à relever

Medioambiental:

- La degradación de los paisajes forestales -incluidos bosques y manglares- afecta a la fertilidad de los suelos, al funcionamiento del ciclo del agua y al almacenamiento de carbono.

- La erosión del suelo, combinada con los efectos del cambio climático, reduce la productividad de la tierra y provoca la sedimentación de ríos y lagos. Esto afecta directamente a los medios de subsistencia de la población.

- La prefectura tiene una cubierta forestal muy baja, del 8,91%, en comparación con el 29,06% a nivel regional y el 24,24% a nivel nacional.

Aspectos socioeconómicos:

- La población depende de la tierra, los ecosistemas y sus recursos, como alimentos, combustible y forraje.

- La degradación y la pérdida de bosques limitan directamente el desarrollo económico sostenible y afectan a los medios de vida de la población local, poniendo en peligro los esfuerzos de reducción de la pobreza, la seguridad alimentaria y la conservación de la biodiversidad. También reduce su capacidad de recuperación frente a los efectos del cambio climático.

- El rápido crecimiento de la población (2,84% anual) aumenta la presión sobre los recursos naturales, como el combustible de madera, acelerando el agotamiento de los recursos.

Ubicación

Procesar

Resumen del proceso

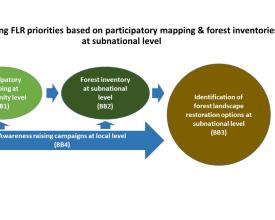

La cartografía participativa a nivel comunitario, incluida la formación de cartógrafos (BB1), sirvió de base para el inventario forestal subnacional (BB2). A partir del inventario, se identificaron y priorizaron las opciones de restauración de forma muy participativa (BB3). Las campañas de sensibilización que se han llevado a cabo a nivel local (BB4) a intervalos regulares proporcionaron el entorno propicio pertinente para las actividades subnacionales.

Bloques de construcción

Cartografía participativa a nivel comunitario

La cartografía participativa fue realizada por las comunidades locales en colaboración con la administración forestal y con el apoyo de la GIZ. Supuso un verdadero enfoque "cantonal" al facilitar reuniones conjuntas entre las comunidades. Éstas prepararon sus mapas de uso del suelo con la orientación de asesores. Esto permitió desarrollar la base de conocimientos pertinente para el uso del suelo y las oportunidades de restauración a escala regional y mostró la importancia de la conectividad de los ecosistemas en un paisaje. Principales etapas de la cartografía:

- Preparación: Análisis y documentación de la información existente, visitas locales a posibles lugares de restauración, reuniones con los líderes de la prefectura y un taller de lanzamiento.

- Campaña de sensibilización en los 9 cantones e identificación de dos cartógrafos locales por pueblo (150 en total)

- Formación de cartógrafos locales en la elaboración de mapas participativos y el uso de herramientas de geoinformación, incluido el GPS.

- Cartografía participativa con 77 comunidades, incluida la identificación conjunta de problemas, la cartografía, la verificación y la comprobación sobre el terreno de las unidades de uso del suelo por parte de expertos y cartógrafos locales.

- Elaboración de los mapas finales, validación y devolución de los mapas a las partes interesadas locales

Factores facilitadores

- Fuerte compromiso político debido a la promesa AFR100 de Togo

- Nombramiento de un punto focal de FLR para el Director de Recursos Forestales (MERF)

- Disponibilidad de expertos locales y apoyo técnico y financiero de los gobiernos togolés y alemán.

- Fuerte colaboración e intercambio de conocimientos entre proyectos a nivel local, nacional e internacional

- Alto compromiso y participación de la comunidad a través de los comités de desarrollo de la prefectura, el cantón y las aldeas, así como de las organizaciones de la sociedad civil.

Lección aprendida

- Fue crucial colaborar con los líderes comunitarios y los comités de desarrollo desde el principio y utilizar sus conocimientos locales sobre los recursos y la utilización de la tierra.

- Las comunidades elaboraron los mapas de uso del suelo por su cuenta, mientras que el proyecto proporcionó las condiciones marco. De este modo se fomentó la apropiación, la confianza y la aceptación entre las comunidades. Les permitió conocer los límites de la tierra y los tipos de utilización, el estado y la ubicación de los ecosistemas (bosques, agrobosques, plantaciones de cocoteros, plantaciones forestales, manglares, etc.) y los tipos de propiedad de la tierra (bosques públicos, comunitarios, privados y sagrados), así como identificar conjuntamente los problemas medioambientales como base para determinar las prioridades de restauración.

- La combinación de procesos de gobernanza y comunicación localmente apropiados (es decir, enfoque consensuado, respeto de las normas consuetudinarias) con enfoques tecnológicos (GPS) tuvo mucho éxito.

Inventario forestal a nivel subnacional

El inventario de bosques naturales y plantaciones se basó en la cartografía participativa. Abarcó las siguientes etapas:

1. Formación de los equipos encargados del inventario forestal

2. Definición de tipos y capas forestales (estratificación): análisis e interpretación de imágenes de satélite RapidEye 2013-2014 (resolución de 5 m x 5 m)

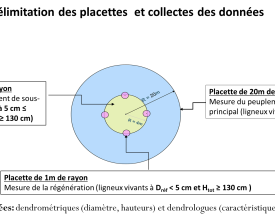

3. Realización del preinventario: Evaluación de los resultados del inventario forestal nacional, preparación del trabajo de campo, determinación del coeficiente de variación y del método estadístico, medición de 20 parcelas circulares. Inventario de la masa forestal principal con un radio de 20 m para muestras ≥ 10 cm de diámetro y ≥ 1,30 m de altura; inventario del sotobosque forestal en parcelas circulares con un radio de 4 m sobre muestras de árboles y arbustos con un diámetro entre 5 y 10 cm abiertos y una altura ≥ 1,30 m.

4. Realización del inventario: preparación del trabajo de campo, medición de 173 parcelas circulares con las mismas características de las parcelas de muestreo que durante el preinventario y con el apoyo de cartógrafos locales.

5. Tratamiento de los datos a nivel de la dirección regional con el apoyo de la unidad de gestión de la base de datos del inventario

6. Zonificación e identificación de las opciones de restauración del paisaje forestal

Factores facilitadores

- Experiencia del personal técnico del MERF en la realización del primer inventario forestal nacional de Togo

- Existencia de unidades de gestión de datos forestales y cartográficos dentro del MERF

- Utilización de los resultados del primer inventario forestal nacional a nivel regional

- Disponibilidad de imágenes de satélite RapidEye (2013-2014)

- Evaluación del potencial de restauración de los paisajes forestales estudio en Togo (2016)

- Orientación y conocimiento de los cartógrafos locales sobre los recursos locales durante el inventario forestal

Lección aprendida

- La identificación y el mapeo exhaustivos de los agentes al principio del inventario fueron cruciales para formar una estructura de coordinación sólida.

- Fue crucial mantener el interés y el apoyo de las comunidades locales en el proceso de inventario, basándose en una comunicación y sensibilización regulares.

- La administración forestal local llevó a cabo el inventario a nivel comunitario de forma muy notable; el proceso participativo situó a los agentes forestales en un nuevo papel de asesores comunitarios muy apreciados y acompañantes para la gestión forestal. La administración, que antes era percibida como una fuerza represiva y una gestora autoritaria de los recursos, fue aceptada por la comunidad como un socio.

- El inventario, que incluyó la identificación de un total de 70 especies arbóreas (incluidas 24 familias y 65 géneros) en las cuatro zonas, aumentó la concienciación sobre la biodiversidad existente y su potencial en el contexto de la restauración del paisaje forestal y la adaptación al cambio climático.

Identificación de opciones de restauración del paisaje forestal a nivel subnacional

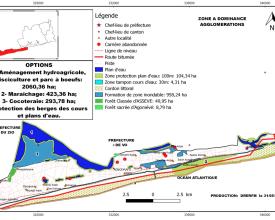

Los resultados de la cartografía participativa y el inventario forestal permitieron evaluar los recursos forestales e identificar opciones prioritarias concretas para la restauración del paisaje en 4 zonas.

Criterios de selección de las opciones prioritarias

- promover la restauración de bosques naturales y ecosistemas frágiles y específicos,

- alcanzar metas y objetivos sociales relacionados con la conservación de la biodiversidad y el bienestar humano,

- aplicarse en el marco de proyectos existentes en distintos tipos de tenencia de la tierra (zonas protegidas, bosques comunitarios o de aldeas, lugares sagrados)

- limitar la fragmentación de las zonas forestales y mantener la conexión de los hábitats naturales.

Las opciones de restauración incluyen las siguientes

- Tierras densamente pobladas (tierras forestales, tierras agrícolas, asentamientos): enriquecimiento forestal, agrosilvicultura, restauración de riberas)

- Tierras agrícolas: mejora de la gestión forestal comunitaria, enriquecimiento de los sistemas agroforestales, zonas tampón alrededor de las masas de agua, bosques madereros

- Bosques densos, matorrales, bosques de ribera y sabanas: restauración de sabanas pantanosas, riberas de ríos y bosques comunitarios, enriquecimiento del barbecho, mejora de la gestión de los pastos

- Humedales, marismas, manglares, praderas: restauración de humedales y manglares

Factores facilitadores

- Estrategia nacional para la conservación, restauración y gestión sostenible de los manglares

- Plan Director Forestal de la Región Marítima

- Estrategia nacional REDD+ en desarrollo

- Metodología nacional de evaluación de las opciones de restauración (ROAM)

- Conocimiento comunitario de los recursos

- Buena colaboración entre el gobierno nacional, regional y prefectural y los representantes de las OSC.

Lección aprendida

- El establecimiento de prioridades fue un proceso muy participativo en el que intervinieron comunidades de los 9 cantones, organizaciones de la sociedad civil, servicios de extensión agraria y administraciones forestales locales, regionales y nacionales.

- Valorar los conocimientos de las comunidades locales en el proceso es extremadamente importante y no se hizo de forma intensiva en el pasado

- La consideración y el respeto de las prácticas ancestrales de las comunidades es clave y debe tenerse en cuenta; el acceso a los bosques sagrados sólo fue posible mediante la adhesión a los procedimientos consuetudinarios y tradicionales

- El conocimiento de las lenguas, tradiciones y procedimientos locales fue un elemento clave del éxito

- La comprensión y la estrecha coordinación con las autoridades locales fue otro factor de éxito

Campañas de sensibilización a escala local

Se llevaron a cabo campañas de sensibilización en cada uno de los 9 cantones. Abarcaron los siguientes elementos:

- visitas de campo para debatir sobre la FLR y la planificación de posibles actividades

- reuniones locales con 77 pueblos, para compartir los resultados de las visitas sobre el terreno

- programas de radio en las lenguas locales

- sesiones de intercambio con el director de medio ambiente de la prefectura

- diseño y elaboración de carteles para cada aldea

Tras la cartografía participativa y el inventario, los resultados se compartieron con las comunidades mediante la instalación de cuadros sinópticos en las propias aldeas, visibles y accesibles para todos. Esto desencadenó debates internos en las comunidades y permitió identificar una o dos opciones de restauración de bajo coste por aldea, que serían aplicadas por las propias comunidades bajo la supervisión técnica del personal del servicio forestal. El suministro continuo de información a través de diversos formatos de sensibilización y reuniones participativas para identificar las opciones prioritarias de FLR en cada uno de los cantones, dio lugar a un gran impulso y legitimidad en las comunidades para participar en la restauración.

Factores facilitadores

- Apertura de los usuarios de la tierra a participar, ya que la mayoría se enfrentan a graves problemas (por ejemplo, falta de leña, degradación del suelo) y ven un beneficio directo en la restauración.

- Visitas preparatorias a los puntos críticos de restauración y talleres que incluyan acuerdos con las autoridades prefecturales y los jefes tradicionales.

- Las ONG locales son socios muy fiables

- El éxito de las actividades de la GIZ en la Reserva de la Biosfera Transfronteriza del Delta del Mono proporcionó argumentos convincentes para apoyar la restauración.

Lección aprendida

- Es esencial, pero también un reto, definir el tamaño de grupo adecuado para llegar al máximo de miembros de las comunidades (a nivel de pueblo o cantón)

- El contenido de los productos y mensajes de comunicación debe adaptarse a las circunstancias de cada cantón.

- El idioma adecuado para la comunicación es crucial: Desde el principio se decidió utilizar el dialecto local para que todos se entendieran.

- La integración de las mujeres en todas las fases del proceso fue crucial para su éxito.

Impactos

- 267 líderes locales y 150 representantes de 77 comunidades locales de 9 cantones participaron en actividades de formación.

- ~Unas 8.000 personas (incluidos grupos de mujeres, jóvenes y asociaciones) participaron en actividades de concienciación; se reforzó su comprensión de los patrones de uso de la tierra y los problemas medioambientales.

- La cartografía ayudó a identificar a los propietarios forestales legales y a crear una base de datos sobre la tenencia de la tierra; esto permite comprender, prevenir y gestionar los conflictos por la tierra

- Se generó confianza y se reforzaron las asociaciones entre la sociedad civil y el gobierno.

- 12 personas de las administraciones forestales locales reforzaron sus capacidades en cartografía e inventarios forestales; esto es crucial para continuar con la restauración del paisaje forestal a nivel nacional y subnacional.

- Se ha establecido un plan de restauración del paisaje forestal que define opciones concretas de restauración en cuatro zonas ecológicas distintas; sienta las bases para mejorar la gestión de la tierra, la adaptación basada en los ecosistemas y la mejora de los medios de subsistencia.

- La administración forestal regional puede reproducir el enfoque en otras prefecturas basándose en una guía de procesos para la cartografía y los inventarios

- Los resultados contribuyen directamente a la gestión de las reservas de carbono terrestre en el contexto de la estrategia nacional REDD+ y los compromisos internacionales en materia de cambio climático (NDC)

Beneficiarios

- 172.148 personas

- jefes de los 9 cantones y 77 pueblos

- presidentes de los comités de desarrollo de los pueblos

- direcciones regionales de agricultura, pesca, ordenación del territorio, silvicultura y medio ambiente

- funcionarios de la administración pública (prefectura, comunas, cantones)

Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible

Historia

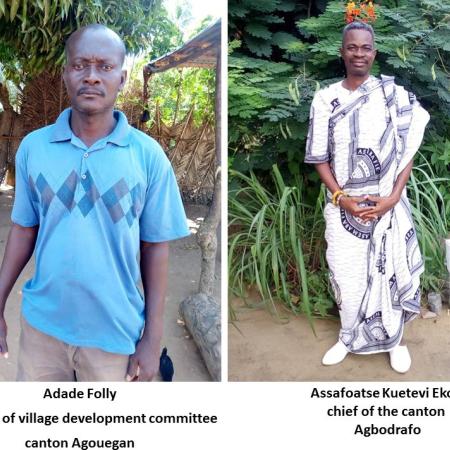

por Adade Folly, presidente del comité de desarrollo del pueblo del cantón de Agouegan:

Seguí el proceso de cartografía participativa de la Dirección Regional de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Forestales con el apoyo de la GIZ a través de ProREDD. Juntos constituimos un mapa de nuestras tierras e identificamos los problemas relacionados con la gestión de los recursos. Gracias a esta actividad, tengo una visión general de las zonas terrestres que hay que gestionar en el cantón. Basándonos en este mapa, pudimos, junto con el comité, planificar una mejor gestión de nuestros recursos, guiados por los proyectos. Podrían explicarnos muy bien, durante la sensibilización, cómo nuestras acciones actuales están degradando los manglares y las consecuencias relacionadas con ello. Como ejemplo, recuerdo que en mi infancia acompañaba a mi padre a pescar en esta zona. Traíamos suficiente pescado que nos servía no sólo para el consumo, sino también para la venta. Hoy en día, los manglares están destruidos, la producción es escasa e incluso nula en determinados periodos del año. Estoy seguro de que la ejecución de las actividades de restauración devolverá la vida a nuestro manglar.

por Assafoatse Kuetevi Ekovi, jefe del cantón de Agbodrafo:

Los bosques sagrados del cantón de Agbodrafo se encuentran bajo presión antropogénica. Esta situación es consecuencia de la erosión costera. El cambio climático ha sido identificado como una de las causas de la erosión, así como actividades humanas como la extracción de arenas marinas y la recogida de piedras del fondo del mar para la construcción. Cada año, el mar se traga unos 5 m de superficie de los pueblos de la costa. El lugar donde se encontraban originalmente estos pueblos ya está tomado por el mar. La necesidad de nuevas tierras y de energía maderera ha provocado una fuerte degradación demostrada por la existencia de las pequeñas islas forestales de unas 2 a 0,5 ha. Las orillas del lago Togo están completamente desnudas y asistimos a una trashumancia ascendente.

El proceso de FLR nos permitió proponer actividades para hacer frente a estos problemas. Así, las opciones propuestas para proteger la costa, la reforestación de las orillas del lago Togo y la creación de zonas designadas para el pastoreo de ganado han sido bien valoradas por toda nuestra población porque permitirán reducir los efectos de la erosión costera, estabilizar la costa y gestionar las pequeñas islas de bosques. La creación de estas zonas de pastoreo nos ayudaría a evitar conflictos entre agricultores y pastores de vacas.