Collaboration intersectorielle et filières technologiques de conservation pour lutter contre la perte de biodiversité dans les zones protégées et conservées du Viêt Nam

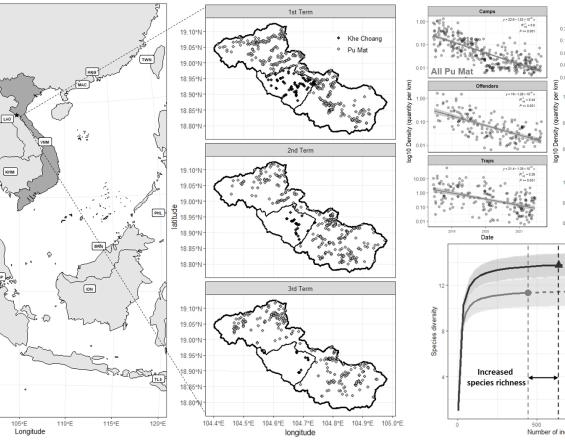

En installant une équipe anti-braconnage basée sur une ONG et en utilisant diverses technologies anti-braconnage dans le parc national de Pu Mat, nous avons été en mesure de tenir des registres spatialement explicites des activités de braconnage, des profils de contrevenants, de mettre en œuvre stratégiquement des systèmes automatisés d'alerte au braconnage et de réduire considérablement le nombre de braconniers, de pièges et de camps dans la zone centrale de la zone protégée, tout en atténuant considérablement les activités de braconnage dans l'ensemble du parc. Ce faisant, nous avons réussi à identifier et à exercer une pression sur les zones de braconnage à haut risque, à éviter le braconnage dans les endroits où se trouvent des espèces hautement prioritaires (en danger et en danger critique d'extinction), à maintenir une base de données opérationnelle sur les infractions et les contrevenants dans la zone protégée afin de mieux comprendre les aspects sociaux du braconnage, et à renforcer la capacité de tous les gardes forestiers de la zone protégée à utiliser eux-mêmes les mêmes méthodes et les mêmes technologies.

Contexte

Défis à relever

- Le braconnage de la flore et de la faune sauvages dans les zones protégées est très répandu au Viêt Nam.

- L'application de la loi dans les zones protégées du Viêt Nam est généralement inefficace en raison de la faible rémunération et du manque de bien-être des gardes forestiers, ainsi que du manque d'outils et de ressources nécessaires.

- Les gardes forestiers sont principalement formés pour se concentrer sur la prévention de la déforestation par l'exploitation forestière illégale ; cependant, la perte de biodiversité n'a pas été un domaine prioritaire jusqu'à ces dernières années parce que la perte de biodiversité est plus difficile à mesurer que la perte de forêt et qu'elle nécessite beaucoup plus de ressources.

- Les gestionnaires et les gardes des parcs nationaux au Viêt Nam n'utilisent généralement pas d'outils de gestion efficaces, de méthodes de collecte de données normalisées ou de bases de données sur les activités illégales dans les zones protégées

- En raison de la rareté des espèces menacées et des perturbations causées par les patrouilles et les enquêtes actives, il est difficile de désigner des endroits hautement prioritaires pour appliquer la pression des patrouilles afin de protéger les espèces menacées en raison des faibles taux de détection.

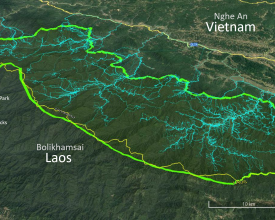

Emplacement

Traiter

Résumé du processus

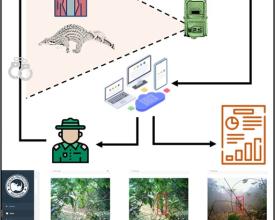

Chacun des éléments ci-dessus interagit avec les autres par le biais des ressources humaines, de l'intelligence et de l'application stratégique afin d'assurer l'efficacité et le succès de la protection globale du site. Notre équipe de lutte contre le braconnage interagit avec les gardes forestiers du gouvernement pour renforcer leurs capacités en leur transmettant des connaissances au fil du temps et en les habituant à utiliser l'outil mobile de collecte de données SMART sur le terrain. SMART est utilisé pour analyser et planifier les patrouilles suivantes en se basant sur les données des patrouilles précédentes collectées auprès de chaque unité. Les caméras anti-braconnage sont installées en fonction des points d'entrée découverts par les patrouilles et des données sur le braconnage à fort trafic. Elles sont installées aux points d'entrée en tant que système d'alerte précoce pour les unités mobiles de gardes forestiers à réaction rapide. Les caméras-pièges fournissent des informations sur les lieux de patrouille prioritaires afin de réduire les activités de chasse dans les zones où se trouvent des espèces rares et menacées.

Blocs de construction

Équipe de lutte contre le braconnage

Les équipes anti-braconnage sont recrutées et financées par Save Vietnam's Wildlife, et approuvées par les gestionnaires des zones protégées qui signent un contrat commun. Elles suivent une formation d'environ un mois sur la législation forestière vietnamienne, l'identification des espèces, l'autodéfense, la formation sur le terrain, les premiers secours et l'utilisation de SMART.

Les patrouilles AP restent avec les gardes forestiers pendant 15 à 20 jours de patrouille dans différentes stations de gardes forestiers chaque mois, et un gestionnaire de données traite, nettoie, analyse et rapporte les données SMART pour toutes les patrouilles au directeur du parc et aux coordinateurs SVW. Au début de chaque mois, un rapport SMART est généré par le gestionnaire de données ; sur la base des informations contenues dans ce rapport, un plan de patrouille est discuté avec le garde forestier et les membres de l'équipe anti-braconnage, puis soumis au directeur de la zone protégée pour approbation ; des unités mobiles sont en attente et dirigées par des gardes forestiers pour répondre rapidement aux urgences, aux endroits situés en dehors des zones de patrouille planifiées ou aux situations accessibles par la route.

Les gardes forestiers ont été formés à l'utilisation de SMART mobile par le biais d'un transfert vertical de connaissances sur le terrain et, à la fin de l'année 2020, 100 % des gardes forestiers (73 personnes) utilisaient tous SMART de manière efficace, ce qui a permis d'accroître la couverture des données de patrouille dans l'ensemble de la zone protégée(figure 1).

Facteurs favorables

- Collaboration entre les assistants chargés de l'application de la loi basés dans les ONG (l'équipe anti-braconnage du SVW) et les gestionnaires des zones protégées et les gardes forestiers.

- Volonté des gardes forestiers ayant un statut et une position élevés d'accepter les conseils et l'orientation adaptative du personnel plus jeune nouvellement formé.

- la volonté des gardes forestiers et des membres de l'équipe de lutte contre le braconnage de s'adapter aux nouvelles technologies et aux nouveaux systèmes opérationnels afin d'atteindre un objectif commun.

Leçon apprise

- Les observations des patrouilles, les informations locales et les tendances des données nous ont appris que les principales périodes d'activité de braconnage dans le parc correspondent aux saisons de récolte du bambou et du miel et aux mois proches de la fête du Têt (Nouvel An lunaire), au cours de laquelle les habitants ont une forte demande de viande sauvage comme cadeau spécial à leur famille et à leurs amis.

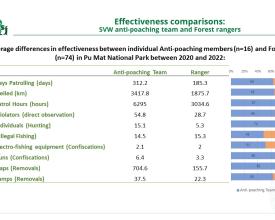

- Lorsqu'elles sont directement comparées, les patrouilles conjointes avec les gardes et les membres de l'équipe de lutte contre le braconnage se sont révélées nettement plus efficaces que les patrouilles des seuls gardes en termes d'activités illégales documentées et atténuées. Cela est probablement dû à l'efficacité de la collecte de données SMART (figure 2).

- Les membres de l'équipe anti-braconnage n'étant pas des fonctionnaires comme les gardes forestiers, ils n'ont pas le pouvoir de procéder à des arrestations, le cas échéant. Par conséquent, les patrouilles composées uniquement de membres de l'équipe anti-braconnage ne peuvent que documenter les menaces humaines actives pesant sur la faune et la flore sauvages, mais pas les atténuer.

Outil de suivi et de rapport spatial (SMART)

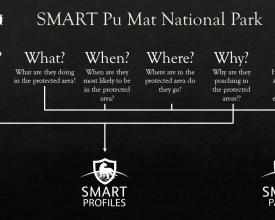

L'outil de surveillance et de rapport spatial (SMART) est à la fois un logiciel et un cadre qui permet aux gardes forestiers et aux patrouilles anti-braconnage de collecter des données géospatiales sur leur smartphone (via l'application mobile SMART), qui agit comme un GPS portable avancé. Lorsque des pièges, des campements illégaux, des animaux ou des contrevenants sont localisés, la patrouille fait un enregistrement en utilisant le "modèle de données" personnalisé de l'application (une personnalisation de l'application qui crée des listes déroulantes et des arbres de décision spécifiques). Le modèle de données du SVW est basé sur la législation forestière vietnamienne, de sorte que lorsque des lacunes techniques sont identifiées dans le modèle de données en termes de procédures d'arrestation, de violations non standard ou d'espèces prioritaires énumérées dans les décrets législatifs, il peut directement informer et améliorer la politique.

Une fois que les données ont été collectées par les patrouilles sur leurs téléphones intelligents, les données de la patrouille (chemins parcourus, kilomètres parcourus, temps passé en patrouille et données enregistrées) seront automatiquement téléchargées sur SMART desktop. C'est là que les gestionnaires peuvent évaluer les points chauds du braconnage afin d'exercer une pression, et cela leur permet également de contrôler l'efficacité des patrouilles elles-mêmes. Avec chaque nouvelle entrée de données, les gestionnaires de données sont en mesure de s'adapter à la situation et d'ajuster leur équipe et les régimes de patrouille en conséquence.

Facteurs favorables

- Coopération des gestionnaires du parc permettant à l'équipe anti-braconnage du SVW d'opérer dans le parc.

- Des gardes forestiers prêts à apprendre de nouvelles technologies et à accepter la planification de la direction de la part d'employés plus jeunes et plus récents qui ont moins d'expérience et d'ancienneté dans la zone protégée.

- Formation intensive et efficace des équipes de lutte contre le braconnage et volonté des membres d'effectuer un travail intensif sur le terrain pour collecter des données et, au bureau, pour gérer et communiquer les résultats des données.

- Logiciel SMART fonctionnel et équipement disponible (téléphones intelligents)

Leçon apprise

- Les gestionnaires de données sont essentiels à la réussite des rapports de renseignement et de la planification, et devraient être séparés des patrouilles afin de pouvoir se concentrer uniquement sur les tâches de gestion des données. Les gardes forestiers et les membres de l'équipe oublient souvent d'éteindre leur enregistreur de traces pendant les pauses, les déplacements et après avoir terminé leur travail. Par conséquent, les gestionnaires de données doivent couper et nettoyer les données pour maintenir l'exactitude des rapports.

- Lors de la phase d'apprentissage, les erreurs sont fréquentes au cours de la première année de collecte et de traitement des données, et il faut s'y attendre. Il est préférable d'identifier les erreurs les plus courantes dès le début et de les traiter avec toutes les patrouilles participantes afin de garantir la viabilité des données à l'avenir.

- SMART Connect est une solution pour centraliser les données collectées dans plusieurs stations ou sites de gardes forestiers. Cependant, la mise en place et la maintenance des serveurs SMART Connect requièrent une assistance technique spécialisée. S'ils sont mis en place par l'intermédiaire d'un service tiers, les problèmes de serveur dépendent de l'assistance technique du service tiers, et les lois sur la souveraineté des données peuvent empêcher complètement l'accès à cette option.

Ressources

Caméras de braconniers

Nos équipes de lutte contre le braconnage ont amélioré le processus de détection et d'arrêt préventif des délinquants qui pénètrent illégalement dans les zones forestières protégées en déployant des PoacherCams, des systèmes de détection automatisés qui fonctionnent grâce à des pièges photographiques et à la classification par intelligence artificielle des humains, des animaux et des véhicules (figure 3). Les PoacherCams sont placées stratégiquement aux points d'entrée des forêts protégées, à proximité des villages locaux et des pistes d'accès. Lorsque les caméras détectent un être humain entrant dans le parc sur les sites d'installation des PoacherCams, le responsable du site reçoit une notification sur son smartphone l'informant de la menace et de l'endroit où il se trouve. Le gestionnaire déploie alors une unité mobile (gardes forestiers) pour surveiller la zone ou documenter les activités d'entrée et de sortie du contrevenant au fil du temps et procéder à une arrestation. Notre système dispose également d'un tableau de bord pour la tenue des registres et la prise de notes, auquel les forces de l'ordre forestières peuvent se référer ultérieurement lorsqu'elles émettent des sanctions et assurent le suivi de leur application avec les forces de l'ordre au niveau communal. Grâce à des patrouilles intensives, nous avons identifié de nombreux points d'accès centraux aux forêts protégées à partir des villages locaux et nous avons installé des caméras de surveillance des braconniers pour les contrôler et prendre des mesures si nécessaire.

Facteurs favorables

- Financement externe par des donateurs désireux d'améliorer les efforts de protection des sites dans les zones protégées et conservées du Vietnam grâce à de nouvelles technologies. Il est difficile d'obtenir l'adhésion du gouvernement pour de nouveaux équipements et de nouvelles technologies avec des ressources limitées jusqu'à ce que la preuve du succès soit faite.

- Soutien de Panthera - à la fois en nous fournissant des caméras et en nous aidant techniquement à les installer sur leur serveur.

- Soutien de Wildlife Protection Solutions pour le réacheminement des messages et des images des caméras vers leur tableau de bord et leur envoi aux gardes forestiers sous forme d'alertes WhatsApp.

- Connectivité du réseau cellulaire

Leçon apprise

- Les braconniers doivent être bien cachés ou installés en hauteur dans les arbres, sous peine d'être endommagés ou volés.

- Une connexion au réseau cellulaire est nécessaire pour que le système envoie des alertes aux téléphones des gardes forestiers, et plus la connexion cellulaire est faible, plus le message mettra de temps à être reçu.

- Parfois, il est préférable d'observer les délinquants qui entrent et sortent de la forêt et d'enregistrer les heures d'entrée et de sortie les plus courantes, puis d'envoyer un garde forestier les attendre sur place, plutôt que d'envoyer des gardes forestiers immédiatement lorsque des alertes sont reçues.

- Certains smartphones ne peuvent pas communiquer avec l'application Camera Trap Wireless Client nécessaire à la configuration de la caméra. L'application doit être testée avant de partir sur le terrain.

- l'application nPerf peut aider à cartographier activement la force de connexion du réseau cellulaire sur le terrain et fournir des informations sur les endroits où optimiser le placement de la caméra.

- Les populations locales s'habituent rapidement aux patrouilles des gardes forestiers et disposent de leurs propres réseaux de communication. Lorsque les habitants des villages voient un garde forestier se diriger vers un sentier par lequel le chasseur du village est entré dans la forêt, ils appellent le chasseur et lui disent d'emprunter un autre sentier pour ne pas se faire prendre.

Ressources

Piégeage systématique à l'aide d'un appareil photo

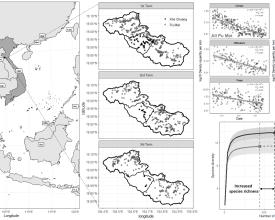

Le piégeage photographique permet de réaliser des études non invasives de la faune et de la flore dans l'ensemble de la zone protégée, ce qui permet de mieux comprendre les points chauds des espèces rares et menacées, tout en fournissant des informations sur les endroits où l'on trouve le plus d'espèces ciblées par les chasseurs. Les pièges photographiques systématiques ont été installés soit en grille fine (zones plus petites avec un espacement de 1 à 2 km entre les stations), soit en grille de parcours (couverture complète de la zone protégée avec un espacement d'environ 2,5 km entre les stations), avec des stations qui contiennent 2 caméras ou plus espacées d'environ 20 m. Les pièges photographiques ont été laissés en place pendant au moins deux semaines. Les systèmes de piégeage des caméras ont été laissés sur le terrain pendant environ 3 mois pour chaque session d'échantillonnage afin de respecter l'hypothèse de fermeture ; les grilles fines pour deux sites ont été répétées à 2 ans d'intervalle, la grille de parcours devrait être reproduite en 2023 (à 5 ans d'intervalle). Des caméras systématiques ont été installées et des données sur les microhabitats ont été collectées à chaque site de station en suivant les protocoles d'Abrams et al. (2018).

Références

Abrams, J. F., Axtner, J., Bhagwat, T., Mohamed, A., Nguyen, A., Niedballa, J., ... & Wilting, A. (2018). Étudier les mammifères terrestres dans les forêts tropicales humides. Un guide d'utilisation pour le piégeage photographique et l'ADN environnemental. Berlin, Allemagne : Leibniz-IZW.

Facteurs favorables

- Financement par des donateurs pour l'achat de pièges photographiques, de piles et d'autres équipements nécessaires

- Aide des gardes forestiers et de la population locale pour installer les pièges photographiques sur le terrain

- Capacité des chercheurs à classer, nettoyer, analyser et rapporter correctement les données.

Leçon apprise

- En raison du flash, il est facile de détecter les pièges photographiques et de les endommager ou de les voler.

- Du personnel expérimenté est nécessaire pour coordonner les efforts de pose des pièges photographiques afin de limiter autant que possible les erreurs. Les erreurs les plus courantes sont les suivantes

- problèmes de réglage de la date et de l'heure

- la végétation n'est pas dégagée de la zone immédiate des pièges photographiques, ce qui entraîne des milliers de photos vierges déclenchées par le balancement des feuilles dans le vent et une perte rapide de la durée de vie des piles, et finalement la mort des piles dans les jours qui suivent la pose.

- un mauvais réglage des pièges photographiques, orientés l'un vers l'autre au lieu d'être éloignés l'un de l'autre, ce qui peut entraîner des enregistrements en double

- Oubli d'allumer les caméras

- collecte incohérente de données sur les microhabitats par les différentes équipes

- La planification préalable du piégeage photographique est essentielle à la réussite et à la réduction des erreurs. La planification préalable doit inclure tout le personnel concerné, être présentée sur des cartes, identifier les chefs d'équipe et passer en revue les protocoles et les listes de contrôle.

- Des photos doivent être prises dans quatre directions autour de l'emplacement de la caméra. Ainsi, si des erreurs sont commises sur le terrain, elles peuvent être quelque peu atténuées par l'évaluation ultérieure des photos, dans la mesure du possible.

Impacts

- Les armes à feu illégales confisquées par km parcouru en 2018-2019 sont passées de 0,016 à 0,003 en 2019-2020 (79,3 % de réduction) à 0,001 de 2020 à fin 2021 (67,6 % de réduction).

- Les pièges retirés par km parcouru en 2018-2019 sont passés de 1,91 à 0,345 en 2019-2020 (81,9 % de réduction) à 0,104 de 2020 à la fin de 2021 (69,9 % de réduction).

- Les campements illégaux retirés par km parcouru en 2018-2019 sont passés de 0,182 à 0,031 en 2019-2020 (82,9 % de réduction) à 0,008 de 2020 à la fin de 2021 (74 % de réduction).

- Le nombre total de contrevenants dans la zone protégée par km parcouru est passé de 0,088 en 2018-2019 à 0,0326 en 2020 (62,9% de réduction) à 0,0075 à la fin de 2021 (77% de réduction).

- Pour l'ensemble de l'année 2021, aucun cas d'exploitation forestière illégale n'a été enregistré dans le parc national de Pu Mat.

- Notre modèle de lutte contre le braconnage, qui a fait ses preuves, est entièrement évolutif et est actuellement étendu à quatre autres parcs nationaux au Vietnam, avec l'espoir d'une nouvelle expansion dans un avenir proche.

Bénéficiaires

- Les gardes forestiers du parc national de Pu Mat

- Les gestionnaires du parc national de Pu Mat

- La faune et la flore du parc national de Pu Mat

Objectifs de développement durable

Histoire

Lam est née et a grandi à Binh Dinh, où elle a appris les arts martiaux dès son plus jeune âge avant de s'inscrire à l'université. Selon Lam, "l'art martial n'est pas seulement un moyen de me protéger, mais aussi une passion" : "L'art martial n'est pas seulement un moyen de me protéger, c'est aussi ma passion. Outre sa passion pour les arts martiaux, elle aime aussi beaucoup la forêt. Après avoir obtenu un diplôme en sylviculture, elle a compris, plus que quiconque, sa responsabilité envers la nature, la forêt et la faune, et a donc choisi de suivre la voie de la conservation. C'est peut-être le tempérament d'une pratiquante d'arts martiaux, combiné à l'empathie pour la nature, qui a fini par déclencher la décision de devenir un anti-pêcheur au SVW.

En juillet 2021, Lam a saisi l'occasion de participer, avec neuf autres collègues, à une patrouille de sept jours dans le parc national de Pu Mat. Elle a connu des endroits et des situations qu'elle n'avait jamais vus de sa vie. Elle a déclaré à propos de ce voyage qu'elle avait "... appris des techniques de survie et [qu'elle avait] eu l'occasion d'entendre et de voir beaucoup de choses nouvelles et merveilleuses". Le voyage lui a révélé tous les défis à venir pour s'entraîner et se former avec détermination et ténacité.

Bien que nous préférions décrire ainsi le travail de conservation, la vérité est que toutes les patrouilles ne sont pas faciles. Il s'agit d'une tâche intense et laborieuse qui, quelle que soit la personne que l'on est, peut parfois donner l'impression d'être épuisée et découragée. "Le fait d'être une fille est plus gênant, surtout lorsqu'il s'agit d'aller se baigner ou lorsque vous êtes dans la "saison des fraises", vous pourriez ne pas résister sans patience et sans un esprit tenace". Et oui, au-delà de nos espérances, cette fille spéciale a réussi sa première patrouille. Elle a conquis la montagne, franchi la cascade, traversé la forêt, vu les nuages voler sous ses chaussures, marché sous la pluie battante de la forêt et posé le pied sur le sentier en pente avec une volonté inébranlable.

"Les patrouilles m'ont apporté une expérience précieuse ; il faut aller sur place pour voir à quel point les efforts de protection de l'habitat sont difficiles", a déclaré Mme Lam. Elle espère que les gens changeront d'avis et apprendront à aimer la nature, afin que toutes les forêts soient un véritable refuge pour les animaux sauvages.

Aujourd'hui, Mme Lam a été affectée à une nouvelle équipe de lutte contre le braconnage qui s'inspire du modèle réussi de Pu Mat pour le mettre en œuvre à Cat Tien et coordonner la région sud du parc national. Elle connaît bien les techniques de patrouille, SMART, la gestion des données, les rapports, SMART Connect, les PoacherCams, et envisage de nouvelles solutions pour les efforts de lutte contre le braconnage à l'avenir.