Incitations fiscales en faveur de la biodiversité pour le réseau de zones protégées d'Afrique du Sud

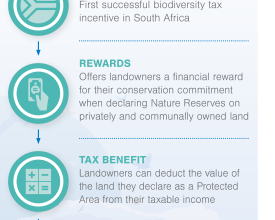

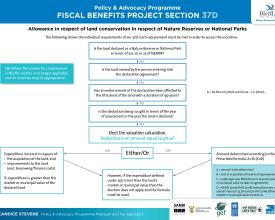

L'Afrique du Sud a identifié l'expansion des zones protégées comme un outil clé pour assurer la persistance de sa biodiversité et des écosystèmes essentiels pour sa population et son économie. Environ 75 % du territoire sud-africain appartient à des propriétaires privés, qui assument la responsabilité de la gestion des zones protégées et doivent donc faire face à des engagements financiers. Le projet "Fiscal Benefits" a été lancé pour tester les incitations fiscales en faveur de la biodiversité en tant qu'avantage financier pour les propriétaires fonciers qui déclarent des zones protégées. Ce projet a commencé par l'introduction d'une nouvelle incitation fiscale dans la législation. L'impact de l'incitation a été testé sur des sites pilotes à travers le pays, ce qui a permis d'inclure avec succès l'allègement fiscal dans une déclaration d'impôts. Cela a ouvert la voie à la reconnaissance financière d'autres zones protégées privées et à la poursuite de la gouvernance et de la gestion des zones protégées d'Afrique du Sud, en s'appuyant sur les éléments constitutifs de la politique et de l'engagement populaire, sur une expertise de niche et sur une communauté de pratique solidaire.

Contexte

Défis à relever

La première incitation fiscale d'Afrique du Sud en faveur de la biodiversité assure la viabilité financière des zones protégées privées et communales, ce qui permet de poursuivre la gestion efficace et souvent coûteuse des sites importants. En assurant une viabilité financière liée à la gestion des zones protégées, on s'attaque au problème des zones protégées mal gérées qui ne parviennent pas à enrayer la perte d'habitat et de biodiversité. Une meilleure gestion favorise également la santé et la fourniture de services écosystémiques. Les propriétaires fonciers et les entreprises bénéficient d'avantages économiques et sociaux, car les allègements fiscaux réduisent le montant de l'impôt dû, libérant ainsi des liquidités indispensables, ce qui garantit la viabilité commerciale continue des activités compatibles avec les zones protégées, telles que l'écotourisme et l'élevage de bétail. Des zones protégées efficaces et durables soutiennent également les moyens de subsistance durables, le développement de l'économie rurale et garantissent la persistance à long terme des zones protégées dans des paysages en concurrence pour les ressources.

Emplacement

Traiter

Résumé du processus

L'introduction réussie de la première incitation fiscale en faveur de la biodiversité en Afrique du Sud a été un processus complexe nécessitant le soutien de nombreuses parties prenantes, notamment le gouvernement, les responsables de la mise en œuvre des zones protégées, les propriétaires fonciers et les communautés. Le processus a également nécessité des tests concrets pour déterminer l'impact des incitations et leurs avantages tangibles sur le terrain. La solution de financement étant de nature fiscale, des compétences spécialisées en matière de fiscalité ont été nécessaires pour mettre en œuvre la solution, au niveau politique et lors des tests sur le terrain. Ces besoins et processus illustrent la manière dont les quatre éléments constitutifs de la solution, à savoir l'engagement politique national, l'engagement populaire, une communauté de pratique cohésive et des compétences fiscales spécialisées, ont travaillé ensemble pour parvenir à ce succès unique. L'engagement politique a permis d'adopter un amendement législatif qui a introduit la nouvelle incitation fiscale, laquelle a ensuite pu être testée auprès des propriétaires fonciers et des communautés au niveau local afin de déterminer son efficacité. Ce test n'aurait pas été possible sans l'implication d'une communauté de pratique collaborative. Ces engagements ont nécessité l'intervention d'un fiscaliste en raison de la nature de l'expertise de niche requise pour la mise en œuvre, ce qui, combiné aux autres éléments constitutifs, a permis de créer une formule gagnante.

Blocs de construction

Engagement politique national

Le succès de l'introduction de la première incitation fiscale sud-africaine en faveur de la biodiversité dans le réseau des zones protégées a commencé avec la modification de la loi sud-africaine sur l'impôt sur le revenu. Sans l'intégration de l'incitation fiscale dans la législation fiscale nationale, la solution n'aurait jamais été possible. Cette première étape réussie a nécessité la mise en place des éléments suivants : Engagement politique national. La modification de la loi sur l'impôt sur le revenu a nécessité un engagement délibéré auprès des principaux ministères et départements nationaux, principalement le ministère des affaires environnementales et le ministère des finances. Le ministère des affaires environnementales a apporté un soutien institutionnel et a approuvé le travail fiscal au niveau national. Cela a permis un engagement direct avec les principaux responsables de la politique fiscale environnementale au sein du Trésor national sud-africain. Cet engagement a été direct, ouvert, collaboratif et positif, et a permis de formuler la première déduction fiscale d'Afrique du Sud visant à soutenir et à avantager les contribuables qui protègent officiellement le patrimoine naturel de l'Afrique du Sud dans l'intérêt public.

Facteurs favorables

- Le succès de cet élément est dû en partie aux relations historiquement positives entre les ministères nationaux et les défenseurs de l'environnement, que le projet a pu exploiter.

- En outre, le chef de projet est un spécialiste de la fiscalité ; sans ces compétences fiscales de niche, l'engagement politique national n'aurait pas été aussi fructueux.

- Les décideurs politiques ont également compris deux points essentiels : les besoins environnementaux du pays et l'utilisation des zones protégées, ainsi que la nécessité de récompenser fiscalement les gestionnaires des terres pour leurs investissements d'intérêt public.

Leçon apprise

Principaux enseignements tirés d'une collaboration fructueuse avec les décideurs politiques nationaux :

- L'utilisation de compétences spécialisées : lorsqu'il s'agissait d'introduire des incitations fiscales spécifiques, un spécialiste de la fiscalité était nécessaire pour en discuter efficacement avec les responsables nationaux de la politique fiscale.

- Une communication délibérée et directe : des informations régulières, professionnelles et précises ainsi que des mises à jour du projet ont permis de renforcer l'engagement politique et de répondre aux attentes.

- Mise en réseau et établissement de relations : le fait de s'assurer que les responsables de la mise en œuvre du projet connaissaient et étaient connus des décideurs politiques a permis de ne pas oublier les objectifs du projet et a favorisé la communication personnelle et la transmission de messages.

- Soutien institutionnel : le soutien institutionnel des principaux ministères a été essentiel pour obtenir le soutien d'autres ministères et décideurs politiques.

- Relations historiques : la compréhension de l'historique des engagements précédents, positifs et négatifs, a été essentielle pour déterminer la manière dont l'engagement politique s'est déroulé.

Ressources

Engagement dans des projets de base

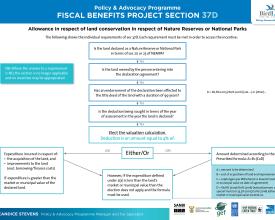

Le projet a lancé un certain nombre de sites pilotes à travers le pays pour tester l'utilisation et l'applicabilité des incitations fiscales en faveur de la biodiversité dans différents contextes. Ces sites pilotes ont permis au projet de s'engager auprès des personnes directement concernées par les avantages fiscaux. Les sites pilotes comprenaient des organismes parapublics, des entreprises internationales, des communautés et des agriculteurs individuels menant différentes activités commerciales. Les sites couvraient également différents biomes et zones prioritaires en matière de biodiversité. Cet engagement au niveau local a été un élément essentiel, car il a permis de concrétiser l'engagement politique du projet, ainsi que la modification de la législation nationale, et de tester concrètement son impact sur le terrain. Pour déterminer l'impact des incitations fiscales sur les propriétaires fonciers déclarant des zones protégées, il fallait engager délibérément les propriétaires eux-mêmes. Cet engagement sur le terrain a permis d'illustrer efficacement les avantages financiers et tangibles de l'incitation. Ces sites pilotes ont également montré que la nouvelle incitation fiscale en faveur de la biodiversité était applicable à tous les types d'entités juridiques en Afrique du Sud et qu'elle pouvait être appliquée à un large éventail d'entreprises et d'activités commerciales et privées. Elle a permis d'appliquer efficacement l'impact fiscal aux propriétaires fonciers et a montré qu'elle était fructueuse et reproductible.

Facteurs favorables

- Les propriétaires fonciers et les communautés qui le souhaitent ont été le principal facteur de facilitation. Sans leur engagement volontaire, l'application pratique des incitations fiscales en faveur de la biodiversité n'aurait pas été possible.

- La communauté de pratique a facilité la présentation des propriétaires fonciers et des communautés et a permis d'établir des relations sur la base des engagements existants.

- Un autre facteur a été la communication claire sur les incitations fiscales et le fait qu'elles étaient testées ; les attentes ont été atténuées et les défis ont été décrits dès le départ.

Leçon apprise

Principaux enseignements tirés de la mise en œuvre du projet Grassroots Engagement :

- Travailler avec une communauté de pratique existante : la participation volontaire était nécessaire pour ce projet. Le fait de travailler au sein d'une communauté de pratique existante a permis de nouer des relations et d'entreprendre un engagement plus délibéré sur la base des relations déjà établies. Reprendre ce processus à zéro prend du temps et, dans ce cas, le projet était soumis à des contraintes de calendrier et de politique.

- Une communication claire et honnête : une fois de plus, la participation volontaire des acteurs de terrain a été nécessaire pour déterminer les objectifs du projet. Une communication claire et honnête a été mise en place dès le début du projet afin d'atténuer les attentes et de ne pas faire de fausses promesses. Les défis et la nature des sites pilotes ont été décrits dès le premier engagement, ce qui s'est avéré fructueux tout au long de la phase pilote du projet.

Communauté de pratique

L'introduction de la première incitation fiscale en faveur de la biodiversité en Afrique du Sud a nécessité le soutien et l'assistance d'une communauté de pratique très efficace et cohérente dans le cadre de l'initiative nationale de gestion de la biodiversité en Afrique du Sud. Les incitations fiscales concernent directement les zones protégées d'Afrique du Sud déclarées sur des terres privées ou communales. Ce contexte nécessitait le soutien des responsables de la mise en œuvre de ces types de déclarations de zones protégées afin de faciliter cette solution unique de financement de la biodiversité. Les responsables de la mise en œuvre de la gestion de la biodiversité en Afrique du Sud sont des représentants du gouvernement national et provincial, des ONG et divers experts et spécialistes. Ils travaillent ensemble au sein d'une communauté de pratique collaborative qui a apporté son soutien total au travail d'incitation fiscale. La nouveauté du travail fiscal, ainsi que les nombreuses composantes du projet qui devaient être menées à bien simultanément, ont nécessité le soutien direct, les conseils et l'assistance de la communauté de pratique. Ce soutien a facilité la mise en place des modules 1 et 2 et a permis de réaliser les objectifs du projet dans l'environnement le plus favorable possible.

Facteurs favorables

- La nature de la communauté de pratique sud-africaine en matière d'intendance de la biodiversité a été le facteur déterminant de cet élément constitutif. La communauté de pratique, dans laquelle le travail sur les incitations fiscales en faveur de la biodiversité a été placé, est par nature collaborative, communicative et cohésive. Cela a permis au travail fiscal, malgré son caractère unique et sa complexité, d'être soutenu et assisté par des membres clés de la communauté de pratique. La communauté de pratique est constituée de cette manière grâce aux experts individuels qui travaillent dans ce domaine.

Leçon apprise

Principaux enseignements tirés de l'utilisation de la communauté de pratique :

- Travail d'équipe : tenter d'introduire la première incitation fiscale en faveur de la biodiversité en Afrique du Sud de manière isolée aurait été une erreur. Les incitations fiscales devaient être introduites dans le contexte de la gestion de la biodiversité en Afrique du Sud. Le projet a été intégré dans cette communauté de pratique au cours de sa phase de définition et tout au long de sa mise en œuvre.

- Partenariats : Dès le début du projet, des partenariats clés ont été recherchés. Ces partenariats, leur soutien, leurs compétences, leurs conseils et leur expertise variée ont été essentiels à la réussite de cette entreprise complexe.

- Retour d'information régulier : le projet a fourni un retour d'information régulier à la communauté de pratique, aux partenariats clés et aux parties prenantes tout au long de sa durée. Ce retour d'information régulier a permis la diffusion des informations. En outre, il a permis aux collaborateurs de rester investis dans la réussite du projet et de garantir un soutien continu.

Compétences spécialisées : Expertise fiscale de niche

Ce projet visait à créer une solution de financement de la biodiversité pour les zones protégées d'Afrique du Sud, fondée sur le droit fiscal. Pour réussir dans cette entreprise, il était essentiel de confier le projet à un spécialiste de la fiscalité. Les précédentes tentatives d'introduction d'incitations fiscales en faveur de la biodiversité en Afrique du Sud ont échoué en raison d'une mauvaise structuration fiscale et de l'absence de tests fiscaux pratiques. Tant pour la modification de la législation fiscale nationale que pour l'appropriation effective des incitations fiscales au nom des propriétaires terriens, il fallait un fiscaliste compétent, qui comprenne à la fois le droit fiscal détaillé et la politique et la législation environnementales auxquelles les incitations fiscales sont liées. La nature tout à fait unique de ce travail nécessitait un ensemble de compétences spécialisées pour garantir une mise en œuvre efficace et efficiente. Cette solution de financement de la biodiversité n'aurait pas pu être mise en place sans un spécialiste de la fiscalité.

Facteurs favorables

Le recours à des compétences fiscales de niche a été rendu possible par le financement catalytique obtenu pour employer ces compétences dans le cadre de ce projet.

Leçon apprise

Les principaux enseignements tirés de l'ensemble des compétences de niche sont les suivants :

- Passerelles intersectorielles : le fait d'attirer différents ensembles de compétences dans le secteur principal de la conservation a constitué une étape catalytique dans l'introduction de cette solution innovante pour la conservation de la biodiversité.

- Sortir des sentiers battus : l'utilisation d'un ensemble de compétences peu courantes dans le domaine de la conservation a permis de créer une solution originale ;

- L'expertise de niche est essentielle pour obtenir des résultats spécifiques et complexes : l'utilisation d'un ensemble de compétences et d'une expertise très spécifiques en matière de droit fiscal a été essentielle pour réaliser cette innovation. L'idée était insuffisante et des compétences clés étaient nécessaires pour une mise en œuvre réussie.

Impacts

La première incitation fiscale d'Afrique du Sud en faveur de la biodiversité assure la viabilité financière des zones protégées privées/communautaires, ce qui permet de poursuivre la gouvernance et la gestion efficace de sites importants qui nécessitent une gestion continue et souvent coûteuse. Le projet profite aux propriétaires fonciers et aux entreprises sur le plan économique et social en leur offrant des allègements fiscaux qui réduisent le montant de l'impôt à payer. L'utilisation d'incitations fiscales en faveur de la biodiversité dans les zones protégées est reconnue comme l'une des solutions BIOFIN du PNUD pour l'Afrique du Sud. Bien que les zones protégées soient considérées comme un outil de conservation essentiel par le gouvernement sud-africain, les ressources et les capacités sont limitées dans les secteurs public et privé, où le financement de la conservation reste une priorité urgente. L'intégration d'un allégement fiscal efficace dans le réseau de zones protégées d'Afrique du Sud fournit un financement de la biodiversité indispensable à la persistance durable de zones protégées bien gouvernées et gérées de manière efficace.

Bénéficiaires

Les bénéficiaires des incitations fiscales en faveur de la biodiversité sont les propriétaires fonciers privés et communaux désireux de déclarer et de gérer des zones protégées, qu'il s'agisse d'agriculteurs individuels, de communautés d'acteurs multiples, d'entreprises ou d'organismes parapublics.

Objectifs de développement durable

Histoire

L'Afrique du Sud est reconnue comme l'un des 17 pays les plus diversifiés au monde. Les zones protégées, déclarées sur des terres publiques, privées ou communales, sont essentielles à la sauvegarde de l'incroyable biodiversité de l'Afrique du Sud et au fonctionnement de l'infrastructure écologique indispensable au bénéfice de ses habitants et de son économie en développement.

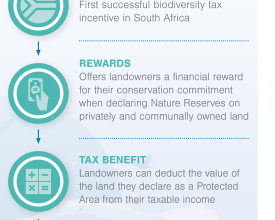

L'extension, la gouvernance et la gestion des zones protégées est une entreprise coûteuse, et des ressources et des capacités limitées, ainsi que d'autres contraintes socio-économiques, entravent ces processus. Les zones protégées d'Afrique du Sud, qu'elles soient privées ou communales, jouent un rôle essentiel dans la résolution de certains de ces problèmes. Toutefois, les propriétaires fonciers désireux de prendre l'engagement ultime en matière de conservation, en reconnaissant officiellement et en gérant des zones protégées sur leurs terres, ont besoin d'aide, que ce soit par le biais de services et de relations de conservation ou d'avantages financiers, tels que la première incitation fiscale d'Afrique du Sud en faveur de la biodiversité : Section 37D.

Dans l'une des principales zones de biodiversité d'Afrique du Sud, riche en plantes endémiques, en gibier du Big Five et en paysages diversifiés, un propriétaire foncier a franchi le pas et a déclaré une réserve naturelle à perpétuité. La Kaingo Private Game Reserve est une zone protégée gérée efficacement et une opération touristique réussie, qui crée des emplois et stimule l'économie rurale de la région. La création et la gestion de cette magnifique réserve et de ses activités d'écotourisme ne sont pas une mince affaire.

Grâce à l'engagement de ce propriétaire foncier en faveur de la conservation, Kaingo a bénéficié d'un allègement fiscal au titre de l'article 37D. En raison des investissements considérables réalisés dans le secteur du tourisme et de la gestion d'une zone de grand gibier, l'avantage financier tangible de cette incitation fiscale innovante renforce la trésorerie de la réserve, garantissant ainsi le succès continu de cette zone protégée. En payant moins d'impôts, des ressources supplémentaires peuvent être mobilisées pour que Kaingo soit mieux gérée et gouvernée et continue à se développer, ce qui profitera à la fois à la biodiversité et à l'économie de l'Afrique du Sud. Sans une gestion efficace, les zones protégées ne parviennent pas à atteindre les objectifs pour lesquels elles ont été créées, et sans opérations commerciales viables et durables pour supporter les coûts de gestion, comme c'est le cas pour Kaingo, il n'est plus possible d'assurer une gestion efficace.

Il est prioritaire de fournir des sources précieuses et alternatives de financement de la conservation de la biodiversité et de récompenser les individus et les organisations désireux d'entreprendre la sauvegarde de notre patrimoine naturel, si nous voulons voir la persistance de la faune et de la flore sauvages et de beaux paysages en Afrique du Sud.

www.kaingo.co.za