Sustainable Banana Fiber Extraction and Composting with Replicable Machine Designs

This solution is part of Sparśa, a Nepali non-profit initiative producing compostable menstrual pads made from locally processed banana fiber.

It describes the first phase of the production chain, detailing how banana pseudostems are sourced from farmers and processed at a factory near the plantations. The solution includes replicable CAD-supported designs for semi-automatic fiber extraction and pseudostem-cutting machines, enabling local manufacturing and adaptation. It also outlines sustainable fiber-drying methods and a circular system that converts the remaining biomass into organic compost fertilizer, which is returned to farmers. The extracted fiber is then turned into absorbent paper sheets used as the core of Sparśa menstrual pads. Overall, the solution strengthens circular economy practices, creates rural employment, empowers women, supports environmentally responsible menstrual hygiene options in Nepal, and offers a model that can be replicated in other banana-growing regions worldwide.

Context

Challenges addressed

Environmental:

Banana pseudostems are commonly burned or left to rot, producing methane and adding to agricultural waste. Processing them into biodegradable fiber and compost reduces pollution, supports regenerative farming, and replaces plastic-based menstrual products.

Economic:

The model strengthens local economies by using abundant agricultural resources instead of imported materials. Farmers gain additional income through pseudostem supply and compost return, while simple, locally manufacturable machines create opportunities for rural producers.

Social:

Sparśa creates dignified employment for women in fiber production and paper making. The approach builds partnerships with farmers, strengthens community collaboration, and improves menstrual hygiene access with affordable, compostable pads. It also helps challenge stigma around women’s health and promotes more inclusive community engagement.

Location

Process

Summary of the process

Sparśa’s production model functions through five interconnected building blocks that form a circular, zero-waste system. The process starts with sourcing banana pseudostems from nearby farms in Nawalparasi, turning agricultural waste into a valuable input. Close cooperation with farmers ensures a steady supply, while the return of compost strengthens collaboration and supports soil regeneration.

The automatic pseudostem cutter then splits trunks into halves, making sheath removal faster, safer, and more consistent. These prepared sheaths move to the semi-automatic fiber extractor, where long, clean fibers are separated using a replicable machine built with locally available parts. This design allows rural workshops to fabricate and repair equipment, reducing dependency on imports and minimizing downtime.

The extracted fibers are processed into paper through washing, beating, cooking, sheet formation, pressing, and solar drying. These paper sheets form the absorbent cores of Sparśa’s compostable menstrual pads. All remaining biomass—unusable trunk parts, leaves, and extraction slurry—is converted into organic compost fertilizer. This completes the cycle by returning nutrients to farmers and ensuring nothing from the banana plant is wasted.

Building Blocks

Sourcing and Sustainable Utilization of Banana Fiber

Bananas are the world’s second-most-produced fruit, cultivated across tropical and subtropical regions between 40°N and 40°S. In Nepal, the most common variety used in Sparśa’s production is Musa paradisiaca (AAB group), locally known as Malbhog. A banana plant takes 9–12 months to mature and continuously forms leaves from its core. These overlapping leaf sheaths form the pseudostem, which grows until flowering begins. After fruiting and harvest, the pseudostem is cut at the base because each stem yields bananas only once. Cutting the stem also stimulates growth of the next pseudostem from the same plant. Over its life cycle, a banana plant may generate around 25 pseudostems, each growing at different speeds and harvested at different times.

This agricultural cycle produces large amounts of waste. Every bunch of bananas harvested corresponds to one pseudostem weighing about 30–40 kg. Farmers often burn these stems or leave them to rot in the field. Burning requires kerosene or other accelerants because the stems are highly moist, leading to greenhouse gas emissions and thick smoke. Leaving stems to decay takes months and occupies substantial space on farmland.

Nepal’s major banana-growing districts include Morang, Jhapa, Saptari, Chitwan, Kailali, and Nawalparasi. Nationwide, banana farming covers around 21,413 hectares and produces approximately 1,284,780 tons of agricultural waste annually. Within these areas, Susta municipality in Nawalparasi stands out with nearly 2,200 hectares of cultivation—one of the highest concentrations in Nepal—generating roughly 132,000 tons of waste per year. This is where Sparśa chose to establish its fiber extraction factory.

Susta’s farming communities are community-led and were open and enthusiastic about collaborating with us, making the partnership both practical and impactful. The area was strategically and socially suitable: raw materials are abundant, and transport distances are short, ensuring trunks can be processed within 72 hours to maintain fiber quality. At the same time, Susta faces deeply rooted social challenges. Women have limited opportunities outside the household and often lack equal rights and representation in community decision-making. Menstrual stigma remains strong. Establishing the factory here allowed us to create dignified employment for women, support their financial independence, and run educational campaigns around menstrual health and environmental sustainability.

Sparśa developed a circular economy model that transforms agricultural waste into opportunity. Banana trunks are collected free of charge from farmers after harvest, and in return the factory provides organic compost produced from the residue of fiber extraction. This non-monetary exchange reduces waste, supports soil fertility, and builds long-term trust with farmers.

Banana plant fibers contain 60–65% cellulose, with smaller fractions of hemicellulose (6–19%), lignin (5–10%), pectin (3–5%), ash (1–3%), and extractives (3–6%). Once a pseudostem reaches the factory, its sheaths are separated. Fiber maturity varies depending on the sheath’s position within the stem—outer layers typically produce stiffer fibers, while inner layers yield softer ones. As a result, extraction can be slightly inhomogeneous unless operators grade and separate sheaths properly. On average, 11 usable outer leaves can be extracted per pseudostem.

Sparśa’s fiber extraction facility processes trunks into fibers used for compostable menstrual pads. Trunks must be processed within 72 hours because their moisture content is 90–92%. Delayed processing triggers decomposition and fermentation, causing discoloration, odor, and microbial degradation. Fiber yield remains low: a 20 kg pseudostem yields around 150 grams of dry fiber, leaving behind large amounts of residue converted into compost.

Additional workers are employed seasonally for 3–4 months (August–November) for harvesting, cutting, and transporting trunks from fields to the factory. The main operational costs include labor and tractor transport. Approximately 6,772 m² of farms can supply enough pseudostems annually for consistent fiber production.

Enabling factors

Abundant Raw Material: Susta’s large banana plantations ensure a steady supply of pseudostems.

Strategic Location: Situating the factory near farms minimizes transport time, preserves fiber quality, and reduces operational costs.

Community Collaboration: Farmers willingly participate because the model solves their waste problem and returns compost that improves soil health.

Circular Economy: The non-monetary trunk-for-compost exchange strengthens trust and reduces financial barriers for both sides.

Social Impact Focus: The factory intentionally centers women’s employment and menstrual health education, creating a deeper community partnership.

Lesson learned

Agricultural Waste Has Hidden Value: Farmers are more engaged when they understand that pseudostems can generate eco-friendly products and fertilizer.

Processing Speed Is Critical: High moisture content makes the stems highly perishable. Delays beyond 72 hours noticeably reduce quality.

Low Fiber Yield Requires Efficiency: A 1% yield demands well-calibrated machines and skilled operators to make the process economically viable.

Fiber Quality Varies Naturally: Standardized grading and clear SOPs reduce inhomogeneity across batches.

Trust Drives Long-Term Collaboration: Consistent communication, compost return, and transparent systems build durable farmer partnerships.

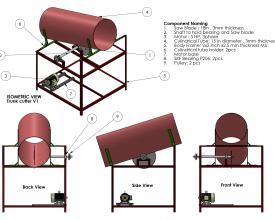

Detailed Overview of Automatic Banana Pseudo Stem Cutter: Process, Operation, and 3D Design Models

After harvesting banana fruits, farmers typically discard the pseudostem—often called the trunk—which actually holds valuable natural fibers within its layered sheaths. However, before fiber extraction can begin, the pseudostem must be split lengthwise to expose the individual sheaths. This step is essential for efficient separation and significantly reduces operator effort during extraction.

Originally, Sparśa used a circular-saw-based pseudostem cutter that allowed workers to split stems into halves. Although functional, this earlier version required operators to continuously lift, balance, and manually push heavy pseudostems through the blade. This made the process physically demanding, time-consuming, and tiring. It also limited throughput, as only one stem could be processed at a time and operator fatigue quickly slowed down the workflow. These constraints made the overall fiber production process less efficient and difficult for long working hours.

To address these limitations, a new and improved trunk cutter was designed. The upgraded model replaces manual pushing with a chain-and-sprocket feed mechanism that automatically grips and advances the pseudostem toward the cutting zone. Instead of relying on a circular saw blade, the machine uses two perpendicular cutting blades positioned to split the stem into two halves in a single pass. This integrated system offers several advantages:

- Reduced physical strain: Operators no longer need to push heavy stems manually.

- Higher throughput: Continuous automated feeding enables faster and more consistent output.

- Improved safety: Guarding and controlled feeding distance keep operators away from moving blades.

- More precise cutting: Automatic feed maintains consistent cutting alignment.

The process works as follows:

- Placement: The pseudostem is placed on the chain-feed platform.

- Engagement: Chains and sprockets securely grip the stem and guide it forward.

- Cutting: The stem passes through two perpendicular blades, which split it cleanly into halves.

- Output: The cut pieces fall onto the collection side, where they can be peeled manually for fiber extraction.

After splitting, operators peel off each sheath layer by hand. Each sheath contains a fibrous zone along with softer inner tissues. Operators trim non-fibrous edges using a knife to remove sections with little or no fiber, ensuring that only fiber-rich material moves to the extraction machine.

This improved cutter has made material handling far easier, reduced operator fatigue, and supported greater consistency in the extraction workflow. It also makes the process accessible for workers with less physical strength, including women who form a key part of the Sparśa workforce.

Enabling factors

Operator experience shaped the design: Inputs from workers who used the earlier circular saw were essential for understanding operational pain points and improving ergonomics.

Use of standard mechanical components: Choosing readily available sprockets, chains, blades, and bearings ensures easy maintenance, local fabrication, and straightforward part replacement in rural settings.

Iterative prototyping with workshops: The new system was developed through close collaboration with local mechanical workshops, allowing adjustments based on real-time testing.

Improved workflow integration: The cutter is designed to fit smoothly into the overall fiber extraction chain, reducing bottlenecks and speeding up subsequent processes.

Lesson learned

Consult operators early and continuously: Their feedback is essential for designing machinery that genuinely reduces workload and improves safety.

Use components available in local markets: Machines relying on rare or custom-made parts become difficult to maintain and repair; accessible components ensure long-term sustainability.

Prioritize durability: Metal thickness, blade quality, and frame construction directly influence machine lifespan and performance under continuous agricultural use.

Pre-delivery testing is essential: Thoroughly testing the machine before sending it to the factory prevents costly downtime and ensures operators receive fully functional equipment.

Training matters: Even with automation, proper operator training significantly improves machine performance and safety.

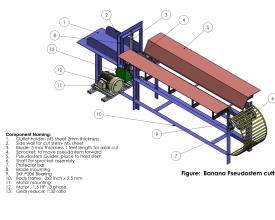

Detailed Overview of Semi-Automatic Banana Fiber Extractor: Process, Operation, and 3D Design Model

Banana fiber extraction offers a sustainable way to transform agricultural waste into a high-value natural material. After the fruit harvest, the banana pseudostem—typically discarded—is rich in long, durable fibers suitable for biodegradable products, textiles, ropes, paper, and sanitary pads.

To extract these fibers efficiently and consistently, Sparśa developed a semi-automatic banana fiber extraction machine that significantly improves output and quality compared to manual scraping.

The machine is a motor-driven system that uses a rotating drum fitted with scraping blades, powered by a 3 HP electric motor. During operation, the operator manually feeds banana sheaths between the rotating roller and a stationary support bar. As the sheath passes through, the blades scrape off the fleshy outer material, separating and releasing clean fibers. An adjustable roller pressure system allows the operator to fine-tune the gap depending on sheath thickness, ensuring smoother operation and higher-quality output.

A simple belt-and-pulley transmission transfers energy from the motor to the drum. The system was intentionally designed to be low-maintenance, easy to repair in rural workshops, and fully compatible with components available in local markets. Its compact welded frame provides stability, even during long operational cycles.

Under typical conditions, the machine produces approximately 5 kilograms of dry fiber per 6–8 hour working day, depending on banana variety, sheath condition, blade sharpness, and operator skill.

Detailed working steps:

- Preparation:

Banana pseudostems are collected, split, peeled into sheaths, and trimmed to lengths of about 1–1.5 meters. - Feeding:

One sheath at a time is fed into the machine, with the roller pressure adjusted to match the sheath’s moisture content and thickness. - Extraction:

The rotating drum removes the water-rich tissue and frees the embedded fibers. The process is repeated on both halves of the sheath to maximize yield. - Drying and Storage:

The extracted fibers are sun-dried or placed in a solar dryer for 1–1.5 days depending on weather. Once dried, they are bundled and stored for the next processing stage.

Enabling factors

Access to Knowledge: Open-source designs and existing models provided a strong foundation for innovation and adaptation to local needs.

Expert Involvement: Collaboration between a fiber engineer and a mechanical engineer ensured design decisions were guided by deep understanding of both material properties and real operational challenges.

Flexible Workshop Environment: An experimentation-friendly workshop allowed repeated prototyping, assembly, testing, and incremental refinements.

Resources and Commitment: Reliable access to banana sheaths, trained technicians, proper tools, and workspace enabled continuous development. Commitment to documentation, troubleshooting, and knowledge sharing further strengthened the process.

Manual Practice Before Mechanization: Early practice with manual fiber extraction provided crucial insights into fiber behavior, sheath variability, and operator ergonomics—insights that directly informed machine design.

Lesson learned

Active Support Is Essential During Fabrication: Even with detailed CAD drawings, close supervision is needed. Workshops often require hands-on guidance to correctly interpret tolerances, assemblies, and material specifications.

Expect the Unexpected: Small misalignments, differences in material stiffness, or unforeseen assembly issues regularly appeared during fabrication. These challenges highlight the importance of onsite adjustments and iterative testing.

Testing Before Delivery Is Critical: Running the machine thoroughly before shipment helps identify and resolve potential issues early, avoiding costly delays and ensuring reliability under factory conditions.

Select Workshops Wisely: Experienced workshops that understand fabrication requirements and read technical drawings accurately significantly speed up the process and improve machine quality.

Extracting Banana Fiber and Fiber Usage

The processing chain begins after the banana pseudostem is collected from nearby plantations. Each pseudostem is made of tightly overlapping leaf sheaths. The outer sheaths and leaves are removed first to expose the usable inner layers. Using the trunk cutter, the pseudostem is halved lengthwise, which makes peeling the sheaths significantly easier and speeds up the extraction process.

The separated sheaths are then fed into Sparśa’s semi-automatic banana fiber extractor. Each sheath contains multiple layers with different proportions of fibrous material and soft inner tissue. During extraction, one end of the sheath is inserted into the machine while the operator holds the other end. The rotating drum and scraping blades break down the inner wall material, releasing the embedded fibers. The softer, water-rich inner layer is scraped away in the process. The operator repeats the extraction on both ends of the sheath to maximize fiber recovery.

For best fiber quality, extraction must occur within 72 hours of harvesting the pseudostem. With a moisture content of 90–92%, the stems decompose quickly. Delayed processing leads to fermentation, discoloration, and unpleasant odor, all of which compromise the resulting fiber.

The Sparśa fiber factory operates three extraction machines, each producing approximately 3 kilograms of dry fiber per day, giving a combined daily output of around 9 kg. Operators typically become proficient within one week of training, and their efficiency improves noticeably with experience, resulting in more consistent fiber output.

The extracted fibers, about four feet in length, are dried immediately after extraction. Drying takes place either in the sun or in the dedicated 251.712 sq. ft solar dryer. Solar drying requires 1–1.5 days in summer and up to 3 days in winter, depending on weather conditions. Once fully dried, the fibers are bundled and stored for the next stage.

Next, the fibers are refined into paper. The long fibers are cut into smaller pieces for easier processing, washed to remove impurities, and fed into a Hollander beater, where they are beaten into a uniform slurry.

Because the final paper is used in sanitary products, hygiene and microbial control are essential. For this reason, we boil the slurry after beating, rather than pre-cooking the raw fibers. Beating takes a long time, and if fibers were boiled beforehand, the extended processing period would increase contamination risk. By boiling the post-beating slurry, we minimize microbial growth and can proceed directly to sheet formation afterward, ensuring hygienic and sanitary-grade paper production.

After cooking, the slurry is diluted with water in a large vat to achieve the correct consistency for sheet formation. A mesh frame is dipped into the vat, allowing a thin, even layer of fibers to settle on its surface and form the initial wet sheet. This sheet is then placed under a pressing machine, which removes excess water and compacts the fibers. Finally, the pressed sheets are transferred to the solar dryer, where they dry into strong, durable banana fiber paper.

Fiber Usage

Banana fiber is a versatile natural material with applications across textiles, ropes, carpets, geotextiles, artisanal crafts, paper products, and eco-friendly packaging. It is valued for its strength, biodegradability, and renewability. Globally, research continues to explore banana biomass as a sustainable alternative to synthetic fibers, supporting circular-economy models and reducing agricultural waste.

At Sparśa, the primary focus is on producing paper-grade banana fiber, used as the absorbent core of Sparśa’s compostable menstrual pads. This aligns with the project’s goals of creating environmentally responsible hygiene products, reducing plastic pollution, and demonstrating how agricultural waste can be transformed into a socially impactful solution.

Enabling factors

Availability of Raw Material: A continuous supply of banana pseudostems from nearby plantations, supported by active collaboration with farmers during post-harvest collection, ensures a year-round, waste-reducing source of raw material for fiber extraction.

Appropriate Machinery to Process: Access to suitable equipment—including trunk cutters for efficient sheath separation, banana fiber extractor machines for moist fiber processing, Hollander beaters for uniform pulping, pressing machines for consistent sheet thickness, and solar dryers for low-cost, eco-friendly drying—is essential to achieve stable paper output.

Suitable Infrastructure: A dedicated fiber-processing facility equipped with extraction, drying, cutting, washing, and storage areas, plus a 251.712 sq. ft solar drying system and reliable water access, provides the necessary foundation for efficient fiber processing and paper production.

Skilled and Trained Workforce: Local operators become proficient within one week of training, allowing efficient machine operation and higher fiber quality. Employing locally trained workers ensures consistency, knowledge retention, and smooth operation throughout the production season.

Lesson learned

Visit Existing Paper-Making Workshops: Visiting paper-making workshops—regardless of fiber type—helps visualize the overall process. The core steps (pulp preparation, sheet formation, pressing, drying) remain the same, enabling a clearer understanding of workflow and machinery.

Manual Trials Before Equipment Investment: Conducting small manual trials before purchasing machinery is highly useful. Producing small pulp batches helps assess banana fiber properties such as bonding ability, strength, and water absorption. These insights guide equipment selection and design adjustments.

Use Visual Learning Resources: Watching banana fiber extraction and paper-making videos online provides valuable visual insights into processing methods, machine setups, operator techniques, and common troubleshooting steps.

Importance of Operator Experience: Due to natural variations in fiber characteristics, maintaining uniform paper quality is challenging. Experienced operators learn to judge refining time, pulp texture, and slurry consistency, which is key to producing stable, high-quality paper sheets over time.

Drying of Fiber-Based Paper for Sanitary Products: When fiber-based paper is used in sanitary pads, it should be dried using an active solar drying system at 60–80°C with controlled humidity. This ensures efficient moisture removal, reduces bacterial risk, and improves product safety.

Banana Plant Waste to Organic Compost Fertilizers

Banana farming produces large volumes of waste, including pseudostems that are unsuitable for fiber extraction, leaves, and slurry generated during the fiber extraction process. Instead of burning this biomass or leaving it to rot—both of which contribute to greenhouse gas emissions—Sparśa converts it into organic compost. This approach reduces methane emissions, supports soil health, and reinforces the project’s zero-waste mission.

Waste Materials Used

- Banana leaves (40%) — chopped into small pieces (3–50 mm).

- Banana trunks (35%) — unusable parts, chopped while fresh for faster decomposition.

- Slurry (25%) — the fibrous waste remaining after extraction, pressed to remove excess water.

- Biochar (optional) — added to improve aeration, microbial activity, and nutrient retention.

The compost recipe aims to achieve an ideal Carbon-to-Nitrogen (C:N) ratio of 20:1 to 35:1, as this ratio influences microbial activity and the speed of decomposition.

Composting Procedure:

- Pre-process materials: Chop leaves and trunk pieces to 3–50 mm. Press the slurry to reduce moisture.

- Weigh or estimate quantities: Use a digital scale at first; later, workers can estimate by volume.

- Mix thoroughly: Combine ingredients in the ratio of 40:35:25 to form a uniform compost pile.

- Adjust moisture: Achieve 50–60% moisture content. Add water if dry; add chopped dry leaves/trunks if too wet.

- Label the pile: Mark each new compost pile with date, batch number, and composition.

- Monitor conditions: Track temperature, moisture, and pile condition using the factory’s monitoring sheets.

Temperature is measured at two depths: 25 cm and 50 cm. Proper composting requires maintaining temperatures between 55–65°C for sanitization. A steady temperature drop or uneven internal heat distribution indicates the need to turn the pile. Extreme temperatures (>75°C) must be avoided to prevent overheating.

After 4–5 months, the compost becomes stable, crumbly, odorless, and ready for agricultural use. The finished compost enriches soil, reduces dependence on chemical fertilizers, and ensures full utilization of banana plant waste.

Enabling factors

Dedicated Expert for Compost Research: A committed intern focused exclusively on compost development enabled systematic experimentation, close observation, data collection, and refinement of optimal recipes. Continuous monitoring was essential for establishing reliable processes.

Availability of Sufficient Waste Materials: The steady supply of banana leaves, trunk pieces, and extraction slurry allowed multiple trial batches. This ensured consistency, improved learning, and enabled the team to refine the compost ratio through practical experimentation.

Strong Commitment to Research and Learning: Studying composting practices through handbooks, online sources, and expert advice helped the team understand microbial processes, temperature control, and pile management strategies suitable for local conditions.

Adequate Space for Composting and Trials: The factory’s spacious site made it possible to maintain several compost piles simultaneously. This allowed comparative learning, smoother turning operations, better airflow, and flexible testing of different pile sizes.

Lesson learned

Material Preparation: Chop banana leaves and trunks while fresh for easier shredding and faster decomposition. Press slurry to reduce excess water. After enough experience is gained, workers can transition from weighing materials to estimating by volume without compromising accuracy.

Temperature Monitoring: Maintain compost temperatures between 55–65°C for effective sanitization. Measure at two depths to ensure uniform heating. Temperature drops or uneven heat distribution indicate it is time to turn the pile. Avoid exceeding 75°C, which can kill beneficial microbes and damage the pile.

Biochar Use: Adding biochar (5–10% by volume) improves aeration, increases microbial activity, and helps retain nutrients. Use dry, crushed biochar made from banana leaves or bamboo. Avoid excessive use in alkaline soils (around pH 8.5), where its benefits are limited.

Turning and Mixing: Turning piles ensures proper aeration, redistributes moisture, and balances temperature. However, it is physically demanding and time-consuming. Investing in a suitable mixing or turning machine greatly improves efficiency and reduces labor requirements.

Impacts

Environmental Impact: Sparśa processes around 350 tons of banana pseudostems each year, preventing open-field decay and reducing methane emissions. By converting plant waste into fiber, paper, and compost, the model lowers environmental pollution and replaces plastic-based menstrual pads with compostable alternatives. The compost returns organic matter to soil, supports regenerative agriculture, and reduces reliance on chemical fertilizers.

Economic Impact: The initiative strengthens rural economies by engaging farmers who benefit from waste removal and access to free compost. The fiber factory and processing facility provide stable jobs for seven local workers, including women trained in machinery operation, fiber extraction, and paper-making. Local workshops benefit from manufacturing and maintaining machines, keeping value in the community and reducing dependence on imported equipment.

Social Impact: The project creates dignified employment for women in a region where economic opportunities have been historically limited. Through training and skill-building, operators gain confidence, independence, and improved technical capacity. Producing compostable menstrual pads supports menstrual dignity and increases access to safe, eco-friendly hygiene products. Community engagement activities help reduce stigma surrounding menstruation and promote more inclusive and environmentally conscious practices.

Beneficiaries

Smallholder banana farmers benefiting from waste removal and compost return; women and men employed in fiber extraction and paper processing; local workshops involved in machine fabrication; and rural communities gaining access to plastic-free menstrual produc

Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF)

Sustainable Development Goals

Story

When Sparśa first explored banana fiber production in Susta, the team expected technical challenges, but their real uncertainty lay in building trust with farmers. For years, banana pseudostems had been treated as waste—heavy, messy, and difficult to manage. Most farmers burned them or left them to rot. So even though exchanging trunks for compost made sense, introducing it required genuine community engagement, especially because the work was linked to menstrual pads, a topic still surrounded by stigma.

During an early visit, Dipisha travelled to meet a group of farmers. She was nervous. In a community where women’s visibility outside the home had long been limited, she wondered whether they would listen to her, especially when speaking about menstrual health.

Yet, the farmers listened carefully. As she explained how pseudostems could be turned into fiber, processed into paper, and eventually made into compostable sanitary pads, they were surprised and intrigued. When she added that the leftover biomass would return to them as free organic compost, the atmosphere shifted.

The biggest surprise was the interest and openness toward menstrual health. The farmers agreed to support the project because they believed women’s wellbeing deserved attention. They were happy that discarded banana trunks could help provide sustainable menstrual products and education.

One farmer spoke about how their region had been overlooked for economic development for too long. Having a manufacturing unit like Sparśa would create employment opportunities and reduce the need for young people to migrate abroad. It felt meaningful to contribute to such a cause.

Several farmers admitted the topic felt sensitive, but they said they were proud that a local initiative could create dignified jobs for women and environmentally friendly products for their community. They appreciated that Sparśa had not come simply to take raw materials, but to build a system that returned value to their fields and families.

With time, trust grew. Farmers began calling ahead to share information about trunk availability and to ask when the next compost batch would be ready. The exchange became more than logistics; it became a partnership rooted in respect, transparency, and shared environmental goals.

This experience remains defining for Sparśa. It showed that conversations about menstrual health can open doors, that circular models resonate with farming communities, and that environmental action begins with human connection.