Ecosystem-Based Adaptation for Climate-Resilient Agriculture in Guatemala’s Highlands

Agriculture in the Guatemalan highlands is a lifeline for local communities but is increasingly threatened by land degradation and climate variability. The Resilient Highlands project supports indigenous smallholders in three micro-watersheds through integrated watershed management and ecosystem service-based planning. By using InVEST models to assess carbon storage, soil retention, and habitat quality, the project informed interventions such as agroforestry, terracing, and forest conservation. Rooted in national forestry policies (PINPEP, PROBOSQUE) and community engagement, the project improved agricultural sustainability, water supply, and biodiversity. The approach strengthened climate resilience and restored vital ecosystem functions while centering gender and indigenous knowledge in its implementation.

Context

Challenges addressed

The region faces multiple challenges. Environmentally, intensive land use and deforestation have degraded soil and reduced water retention capacity. Socially, indigenous smallholders lack access to technical assistance and sustainable farming practices. Economically, agriculture depends on rain-fed crops and is highly vulnerable to changing precipitation patterns and declining soil fertility. Surveyed farmers observed drying springs, reduced rainfall, and erosion. Without action, productivity, food security, and biodiversity would continue to decline. The project addressed these issues through landscape restoration, improved resource governance, and integration of ecosystem services into decision-making.

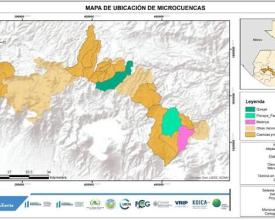

Location

Process

Summary of the process

The three building blocks worked in synergy. Ecosystem service modelling identified priority areas and land use impacts. Alignment with national incentive programs enabled resources for implementation. Participatory planning grounded decisions in local realities, ensuring interventions were socially acceptable and ecologically effective. Together, they fostered resilience by combining scientific assessment, policy tools, and community wisdom.

Building Blocks

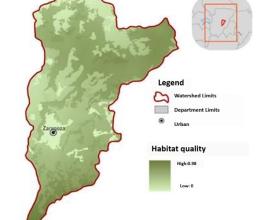

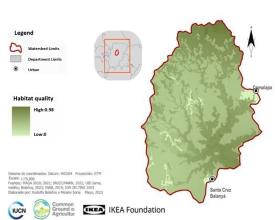

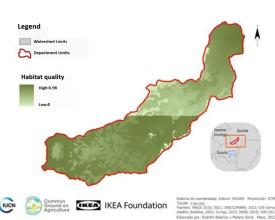

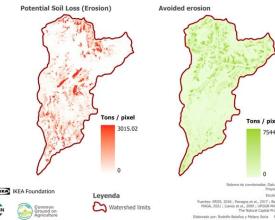

Ecosystem Service Modelling with InVEST for Landscape Planning

To understand how different land uses affect ecosystem functions, the project applied InVEST modelling tools to map and quantify carbon storage, sediment retention, and habitat quality in three micro-watersheds. This allowed the project team and local stakeholders to see the “what” (the ecological state of the landscape), “why” (which land uses provided more benefits), and “how” (where interventions were needed). For instance, forest and shrubland areas were found to store significantly more carbon and reduce erosion compared to basic grain croplands. This modelling helped prioritize areas for restoration and agroforestry. The visual outputs and metrics supported evidence-based discussions with communities and decision-makers, integrating ecological science into watershed-level planning.

Enabling factors

Smallholder farmers, especially indigenous families in the Quiejel, Balanyá, and Pixcayá–Pampumay micro-watersheds; national partners—the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Food of Guatemala (MAGA) and the National Institute of Forests (INAB); and the ecosystems that will benefit from improved land management

Lesson learned

Making ecosystem functions visible through maps helped bridge knowledge gaps and build trust. However, technical complexity required training and translation into accessible formats. Some areas lacked detailed data, so local observations were essential for model validation. Combining modelling with participatory methods made the findings more relevant and actionable.

Policy Alignment with PINPEP and PROBOSQUE for Smallholder Incentives

To promote sustainability and incentivize adoption of restoration practices, the project aligned its interventions with Guatemala’s national forestry incentive schemes—PINPEP (targeting smallholders) and PROBOSQUE (supporting forest management and agroforestry). This approach answered “what” (financial support available for conservation), “why” (incentives reduce the cost barrier for farmers), and “how” (linking project actions with formal application support). Farmers engaged in agroforestry, reforestation, or conservation activities were guided through the process of registering for these programs, ensuring long-term continuity and co-financing. This institutional alignment also ensured that restoration efforts complied with national environmental priorities.

Enabling factors

A strong policy framework, INAB collaboration, farmer interest in incentives, and field staff supporting application processes enabled smooth integration. National recognition of smallholder needs and pre-existing program budgets were also essential.

Lesson learned

While alignment with national programs strengthened sustainability, bureaucracy and paperwork were hurdles for farmers. Simplifying the application process and building farmers’ confidence in engaging with institutions proved essential. Having local facilitators familiar with both community dynamics and institutional procedures was key to success.

Participatory Planning and Indigenous Knowledge Integration

Recognizing that local communities hold deep environmental knowledge, the project conducted household surveys and community dialogues to map perceptions and practices around soil, water, and land use. This building block answered “what” (the lived experiences and practices of smallholders), “why” (planning must reflect cultural context), and “how” (engaging farmers in co-design). Farmers shared observations about decreasing water availability, shifting rainfall, and soil degradation. These insights complemented scientific models. In response, the project promoted culturally rooted practices like terracing, organic fertilization, and home gardening. Gender-sensitive approaches empowered women as leaders in ecological restoration and household resilience.

Enabling factors

Deep-rooted cultural knowledge, community trust, and strong leadership enabled inclusive planning. Facilitators fluent in local languages and customs built bridges between science and tradition.

Lesson learned

Respecting indigenous knowledge fostered ownership and sustainability. Creating space for women and youth increased innovation and resilience. The process strengthened community cohesion and built confidence in local solutions. Replication requires long-term engagement and respect for socio-cultural norms.

Impacts

Environmental benefits include improved carbon storage in shrubland and forest areas, erosion control of up to 200 tons of soil retained annually, and enhanced habitat quality (reaching 0.95). A local ecosystem services survey found that 62.5% of households cultivate diverse home gardens, 89% associate soil quality with crop yields, and 78% have noticed water declines, reflecting increased awareness of environmental changes. Economically, linkages with PINPEP and PROBOSQUE provided farmers with payments and technical support. Culturally, the project strengthened recognition of indigenous knowledge and women’s contributions to sustainability.

Beneficiaries

Smallholder farmers, especially indigenous families in the Quiejel, Balanyá and Pixcayá-Pampumay micro-watersheds; national partners (MAGA, INAB); and the ecosystems benefiting from improved land management.