The Green Project Model: Regreening Rwanda Bugesera for People and Nature

The Green Project in Gashora Sector, Bugesera District, Eastern Rwanda, transformed the country’s driest agro-ecological zone through regenerative, farmer-led land restoration. Facing severe land degradation, poor soil fertility, and widespread poverty, the project implemented agroforestry-based conservation agriculture using shrub-tree hedgerows, rotation cropping, and organic mulching. Designed as a low-cost, inclusive and replicable model, the project improved soil health, enhanced biodiversity, increased yields, and diversified household incomes. Starting with just six farmers, it now engages over 1,000. The intervention shows how Nature-based Solutions (NbS) tailored to local conditions can reverse degradation, boost resilience, and uplift rural livelihoods.

Context

Challenges addressed

Before intervention, Bugesera's smallholder farmers cultivated severely degraded land lacking organic inputs due to limited livestock and dependence on crop residues for cooking fuel. The use of mineral fertilizers worsened compaction, nutrient imbalance, and invasive species spread. Persistent soil degradation led to poor yields, food insecurity, and poverty—fuelling school dropout and social vulnerability. Farmers also lacked confidence in agroforestry due to fears of lost crop space. The project addressed this by designing farm layouts that integrated trees and crops without reducing productivity, and by providing cooking energy, forage, and training to reduce pressure on soil resources.

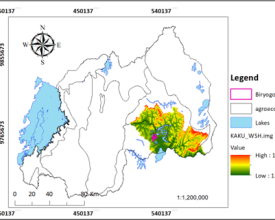

Location

Process

Summary of the process

The project began with six farmers and used a bottom-up, participatory approach. After identifying interlinked causes of land degradation—such as lack of livestock, poor soil fertility, and cooking energy scarcity—farmers co-designed a solution centered on agroforestry-based conservation agriculture. Contour hedgerows, rotational cropping, and mulch application were adopted, with complementary support including small livestock and supplementary irrigation. As benefits became visible (improved yields, forage, cooking energy), farmer participation expanded exponentially. Continuous learning and flexible implementation allowed new practices to evolve with field experience. Soil health and biodiversity indicators were monitored to guide improvements, while peer-to-peer exchange promoted replication.

Building Blocks

Agroforestry-based Conservation Agriculture with Tree-Shrub Hedgerows

The project introduced tree and shrub hedgerows along contour lines, intercropped with maize and beans, to rebuild soil fertility and control erosion. Double hedgerows spaced at 10m intervals and inter-row distances of 30cm allowed farmers to grow up to 121 trees and 8,623 shrubs per hectare without compromising crop yields. Trees provided shade, cooking fuel, and biomass; shrubs offered forage and green manure. Mulching from biomass and crop residues maintained soil moisture and improved microbial activity. This system proved to increase yields, reduce crop failure during dry spells, and restore degraded lands.

Enabling factors

Farmer-centered co-design and participatory learning built trust and ensured solutions were tailored to farmers' realities. Training in agroforestry and hedge management enabled proper establishment and maintenance of the hedgerows, which was key to sustaining the productivity of both trees and crops. Local perception shifted positively as demonstration plots showed that tree integration could coexist with profitable farming. The availability of multipurpose tree and shrub seedlings ensured the right species could be chosen for multiple uses—cooking fuel, fodder, and mulch. Integration of small livestock and access to supplementary irrigation improved nutrient cycling and reduced vulnerability to climate stressors, further enhancing the agroforestry system’s resilience and farmer buy-in.

Lesson learned

Initial farmer skepticism stemmed from concerns that trees would reduce cropland. Success was driven by design optimization that reassured farmers of no productivity loss. Demonstration effects and participatory processes accelerated adoption. However, lack of traditional knowledge on tree/shrub management required continuous training. Soil health improved most where mulch was abundant, emphasizing the role of organic matter. Project sustainability could be challenged if not integrated into broader agricultural extension and policy frameworks.

Participatory, Dialogical Implementation and Farmer Empowerment

The intervention followed a dialogical, farmer-centred, problem-solving approach. Starting with six farmers, the project used community learning to co-design interventions. It scaled gradually by demonstrating visible results. Farmers participated in identifying soil degradation drivers and jointly designed context-appropriate agroforestry systems. Through empowerment and co-learning, the number of farmers rose to over 1,000. This process built ownership, strengthened resilience, and ensured equity. Children and youth were engaged through household and school-based activities, promoting early NbS awareness.

Enabling factors

In this project, the The Rwanda Agriculture Board has partnered with SOS Children's Villages Rwanda, a child protection agency, which actively advocates for the promotion of childcare and child protection. This partnership has linked children families with nature conservation and sustainable agriculture. It reinforced the institutional bond between agriculture-environment protection and child protection institutions.

Farmer trust and respect for peer experience encouraged experimentation and openness to change. Inclusive engagement of women and children ensured that diverse perspectives and needs were represented, reinforcing social cohesion and sustainability. The use of non-hierarchical, dialogical facilitation allowed local knowledge to shape interventions, increasing legitimacy. Observable success from early adopters created powerful peer motivation, with neighbours emulating successful farmers. This ripple effect reinforced community ownership and scaled uptake beyond initial project boundaries.

Lesson learned

Genuine inclusion and dialogue transform mindsets more effectively than top-down training. Farmers' perceived agency was essential. However, scaling was initially slow, requiring patience and visible benefits. Ensuring community ownership demanded consistent facilitation and monitoring. Institutional sustainability remains a challenge given SOS is not an agricultural agency.

Impacts

- 1,000+ farmers now apply the regenerative system

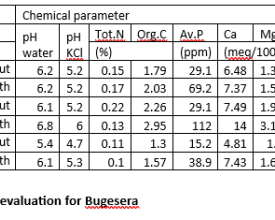

- pH, organic carbon, nitrogen, and cation exchange capacity significantly improved (e.g., CEC rose from 7.4 to 16.2 meq/100g in one case)

- Landscape now contains thousands of trees and shrubs

- Risk of crop failure reduced through supplemental irrigation and improved soil health

- Crop productivity and household income increased

- Livestock and cookstoves reduced reliance on external inputs

- More nutritious diets and fewer school dropouts reported

- Soil biodiversity (insects and microbes) measurably increased

Beneficiaries

Smallholder farmers in Gashora sector, including women and youth; their children; rural schools and communities