Under the application of the trap for intermittent harvest, the best results were achieved with the following combination of variables: maize bran (supplementary feed) x maize bran (trap bait) x O. Shiranus (species) x 2 fish/m2 (stocking density).

The total yields under this combination were 25 percent higher than in the control group with single batch harvest. A higher stocking density (3 fish/ m2) led to a slightly higher total harvest in the control group, but to a lower net profit. The use of pellets reinforced both effects and was the least economical.

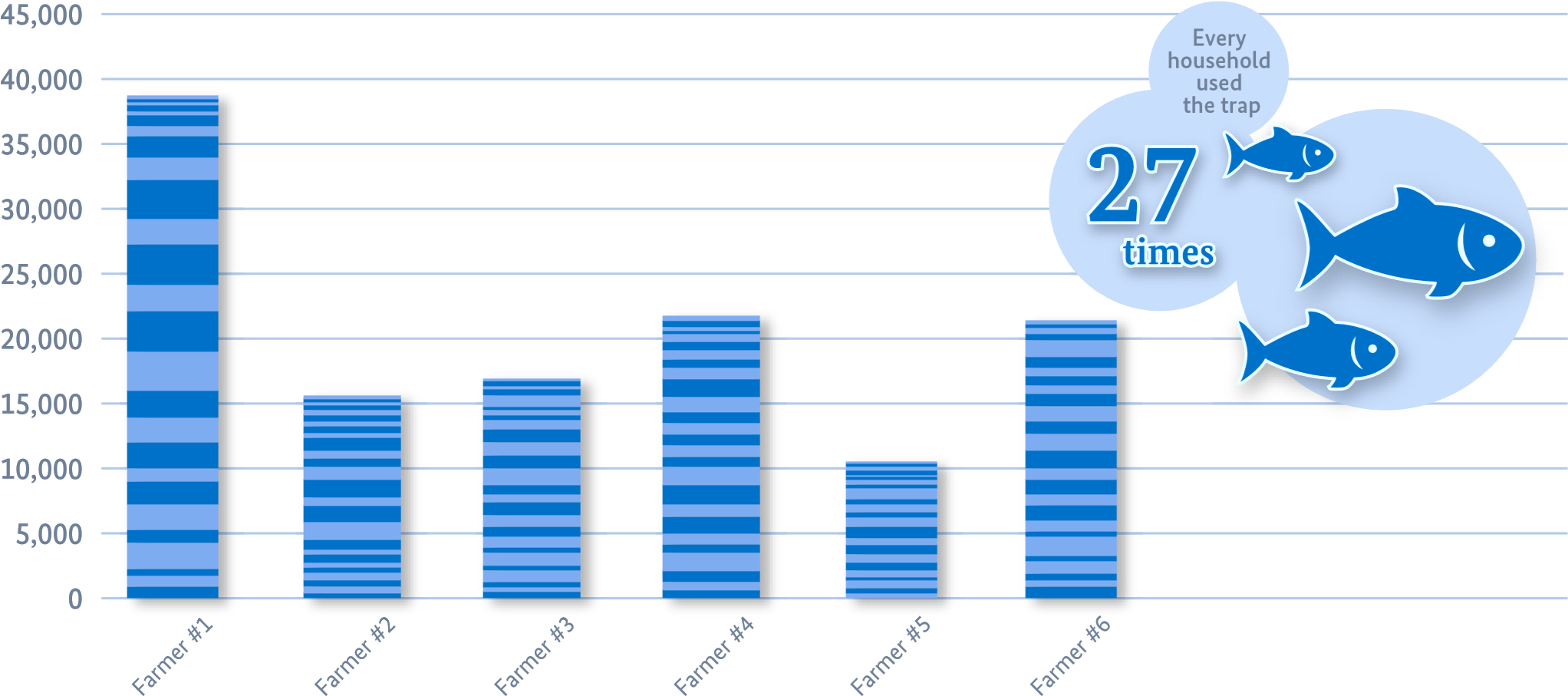

Results from the on-farm trials (see Figure 1) have demonstrated the functionality and the excellent catch effect of the traps. Over the three-month on-farm trial period, the trap was used 2 to 3 times a week and a total of 27 times. On average, around 120 small fish – an equivalent of 820 grams – were caught each intermittent harvest. With the use of the trap, all households reported that they now eat fish twice a week. Before that, fish consumption was between one and four times a month.

The benefits:

Reducing the competition for oxygen and food among the fish in the pond and thus measurable increase in yield.

Improved household consumption of small, nutritious fish and better cash flow.

Success factors:

Traps are easy and inexpensive to build (USD 3).

Traps are easy to use, also for women.

Directly tangible added value thanks to easy and regular access to fish.

Examples from the field

Overall, the user experience of households engaged in the on-farm trials was very positive: “As a family we are now able to eat fish twice and sometimes even three times a week as compared to the previous months without the technology when we ate fish only once per month.” (Doud Milambe)

“Catching fish is so simple using the fish trap and even women and children can use it.” (Jacqueline Jarasi)

“It is fast and effective compared with the hook and line method which I used to catch fish for home consumption that could take three to four hours but to catch only three fish and thus not enough for my household size.” (Hassan Jarasi)