Creating Lands of Opportunity: Sustainable Agriculture and Land Restoration in Burkina Faso

This project empowered communities in Burkina Faso’s Centre-East and Centre-South regions to transition toward sustainable agriculture and landscape restoration. With support from the IKEA Foundation, UNCCD Global Mechanism, and the Italian Ministry of Environment and Energy Security, the project reached 300,000 people (50% women, 50% youth). It increased agro-sylvo-pastoral production, restored over 54,000 ha, and strengthened local associations and governance. Through inclusive participation, communities adopted legal texts protecting 37,500 ha of ecological corridors. The intervention improved food security, incomes, biodiversity, and local decision-making capacity while aligning with Nature-based Solutions standards. Its successful co-production approach and restoration-business linkage offer high potential for replication across the Sahel.

Context

Challenges addressed

In Burkina Faso’s Centre-East and Centre-South regions, rural communities faced interconnected environmental, social, and economic challenges. Years of unsustainable land use, climate variability, and deforestation led to severe land degradation, desertification, and biodiversity loss. Erratic rainfall and prolonged droughts reduced agricultural productivity, threatening food security. Socially, local populations—especially women and youth—lacked access to training, resources, and land-use decision-making processes, limiting their resilience. Economically, many relied on low-value, climate-sensitive activities without alternative income options or access to markets. Weak local governance structures further hindered sustainable land management. The project addressed these complex, layered challenges through a nature-based, inclusive, and landscape-scale approach that integrated ecological restoration with livelihood development and community empowerment.

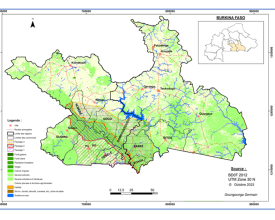

Location

Process

Summary of the process

The co-production of restoration practices and inclusive governance formed the project’s core. Restoration actions were designed to benefit both biodiversity and livelihoods, while governance reforms provided the legal structure for sustaining and scaling these benefits. The building blocks complemented each other: ecological actions created value, while participatory governance ensured that communities could protect, manage, and benefit from restored landscapes. The creation of legal corridors formalized this synergy, ensuring continuity. Capacity building, community organizing, and legal empowerment interacted dynamically, resulting in stronger institutions, greater inclusion, and improved land health. These interlinked processes helped shift communities from degradation and marginalization toward empowerment and resilience.

Building Blocks

Co-Production of Land Restoration and Income-Generating Solutions

The project integrated ecological restoration with local economic development through a co-production model rooted in community needs and knowledge. Interventions included assisted natural regeneration, use of manure pits, nursery establishment, beekeeping, agroforestry, and conservation of wooded areas. These restoration techniques were linked to income-generating activities—e.g., production and marketing of honey, shea butter, soumbala, and soya products. Communities received training, equipment, and support in forming or strengthening cooperatives. The integration of sustainable practices into value chains increased ownership and accelerated adoption. Community-led planning further ensured that ecological outcomes also served livelihoods. A unique aspect was the legal recognition and management of ecological corridors that improved biodiversity while securing local rights to restored land. This model strengthened food security, social cohesion, and economic inclusion while rehabilitating degraded landscapes.

Enabling factors

- Established cooperatives and community groups facilitated coordinated action.

- Local ecological knowledge enabled effective implementation.

- Provision of tools, training, and processing equipment allowed communities to operationalize improved practices.

- Legal frameworks supporting participatory restoration planning legitimized local actions.

- Multi-actor partnerships ensured long-term support, policy alignment, and technical backing.

Lesson learned

Restoration efforts gained traction when aligned with livelihoods. Community buy-in was strongest where immediate benefits—such as improved yields or income—were visible. Familiar practices like manure pits and tree regeneration gained new relevance through enhanced market connections and training. Capacity building must be continuous and locally adapted. While technical and ecological knowledge was strong, access to water during dry seasons emerged as a key limitation, requiring future integration of water solutions. Security challenges in some areas highlighted the need for decentralized, flexible implementation and strong local leadership

Inclusive Landscape Governance and Legal Empowerment

Participatory land governance was central to the project’s long-term success. Communities were engaged in developing and adopting legal texts for two ecological corridors (Nazinga and Nazinon), covering a total of 37,500 ha. These corridors reconnect critical biodiversity areas while being managed by local populations. Traditional and local authorities, women, and youth participated in land-use planning and landscape governance training. Communities also contributed to restoration and management plans for 16,547 ha. By strengthening local legal literacy and providing technical guidance, the project ensured that biodiversity conservation, land use rights, and sustainable livelihoods were legally protected. The institutionalization of co-managed landscapes enabled communities to transition from passive beneficiaries to rights-holders and stewards.

Enabling factors

- Stakeholder platforms enabled inclusive dialogue and planning.

- Legal support and government recognition legitimized local decisions.

- Training on land rights and local governance empowered communities.

- Traditional leaders’ involvement bridged customary and formal systems.

- Commitment from public authorities ensured follow-through and upscaling of community-led governance innovations.

Lesson learned

Establishing ecological corridors through participatory governance fostered community ownership and legal empowerment. Flexibility in accommodating traditional norms within formal structures improved legitimacy. Trust-building and sustained dialogue were critical—especially where land tenure was sensitive. Challenges included delays in legal processes and the need for continuous technical and legal support to sustain management plans. Clear roles, inclusive structures, and local champions were essential to maintain momentum. Future efforts should integrate financing strategies to support long-term corridor management and policy advocacy at national levels.

Impacts

The project achieved major environmental, social, and economic impacts. Environmentally, over 54,000 hectares benefited from biodiversity restoration, including 16,547 ha under active land management plans using native herbaceous and woody species. Two major ecological corridors totaling 37,500 ha were legally established, strengthening habitat connectivity. Socially, 300,000 individuals (50% women, 50% youth) gained new knowledge, technical skills, and access to decision-making. More than 3,500 producers improved their livelihoods, producing 2,733.9 tonnes of crops, non-timber forest products, and honey in the first cycle. Economically, sustainable value chains were strengthened around local products like soumbala, shea butter, and soya, enhancing food security and household incomes. Medicinal plant availability was improved on 19 ha, contributing to local health systems. Cooperatives grew in functionality, visibility, and gender inclusivity, while community governance capacities expanded across restored landscapes.

Beneficiaries

The 300,000 direct beneficiaries included farmers, women’s cooperatives, youth, traditional healers, and community leaders. Local government staff and extension agents also benefited through capacity building and participation in landscape planning processes.