Defining a Good Menstrual Pad: A User-Centered R&D Process in Nepal

This initiative is part of the Sparśa Solution, a Nepali non-profit company that locally produces and distributes compostable menstrual pads with an absorbent core made from banana fibre. The solution focuses on defining what makes a good menstrual pad, combining research, prototyping, quality assurance, and continuous user feedback.

The process began with a nationwide study of 820 women and girls, whose insights shaped the pad prototypes. Pads were then developed in two phases: manually and later with machines, testing different material combinations to balance absorbency, comfort, and compostability. Internal testing protocols and certified laboratory analysis ensured hygiene and compliance with national and international standards.

Feedback from users, collected through simplified surveys in Nepali and English, provides the basis for ongoing refinement of both pad design and packaging. By linking social research with technical innovation, the solution delivers pads that are safe, eco-friendly, and culturally acceptable.

Context

Challenges addressed

Environmental: The market is dominated by cheap, plastic-based pads that create long-term waste. Using natural fibres like banana and viscose reduces pollution but requires stricter hygiene control, as compostable materials are more vulnerable to bacterial growth.

Social: Menstrual stigma makes open discussion difficult, and many users are unfamiliar with concepts like “biodegradable.” Social desirability bias can distort feedback, requiring sensitive, trust-based approaches.

Economic: Locally made pads must compete with subsidized imports, while raw material imports, bureaucratic delays, and certification processes increase costs. Ensuring that pads remain affordable while meeting quality and safety standards is a constant balancing act for the project.

Location

Process

Summary of the process

The four building blocks form a continuous, user-centered R&D cycle. Field Research & User Insights (Block 1) generated the evidence base on menstrual practices, product preferences, and cultural barriers, ensuring that pad development started from real user needs. These insights fed directly into R&D, Design and Prototyping (Block 2), where different material combinations and pad structures were tested, balancing absorbency, retention, comfort, and compostability. Findings from internal trials were then verified through Quality Assurance (Block 3), combining in-house protocols with certified lab testing to ensure safety, hygiene, and compliance with national and international standards. Finally, Feedback-Based Optimization (Block 4) closed the loop by systematically collecting user experiences from schools and communities, allowing continuous product refinement in design, performance, and packaging. Together, the blocks connect social research, technical innovation, quality compliance, and user feedback into an integrated cycle that makes Sparśa pads safe, sustainable, and widely acceptable.

Building Blocks

Field Research & User Insights: On menstrual product access and their preferences in Nepal

This building block outlines the findings and methodology of a nationwide field study conducted in 2022, which informed the Sparśa Pad Project. The research examined menstrual product usage, access, stigma, and user preferences among 820 Nepali women and adolescent girls in 14 districts across all seven provinces.

Using a structured face-to-face interview approach, the team employed ethically approved questionnaires administered by culturally rooted female research assistants. This method ensured trust, context sensitivity, and accurate data collection across diverse communities. The interviewers were trained in ethical protocols and worked in their own or nearby communities, thereby strengthening rapport and enhancing their understanding of local norms, power relations, and languages.

Key findings revealed a high reliance on disposable pads (75.7%) and ongoing use of cloth (44.4%), with product preferences strongly shaped by income, education, and geography. Respondents prioritized absorbency, softness, and size in menstrual products. While 59% were unfamiliar with the term “biodegradable,” those who understood it expressed a strong preference for compostable options, over 90%. Importantly, 73% of participants followed at least one menstrual restriction, yet 57% expressed positive feelings about them, seeing them as tradition rather than purely discriminatory.

These findings directly shaped the design of Sparśa’s compostable pads, informed the user testing protocols, and guided the development of targeted awareness campaigns. The accompanying link and PDFs include a peer-reviewed research article co-authored by the team and supervised by Universidade Fernando Pessoa (Porto, Portugal), as well as informed consent forms, a statement of confidentiality, and a research questionnaire. These documents are provided for practitioners' reference or replication purposes.

Why this is useful for others:

For Nepali organizations and local governments:

- The study provides representative national data to inform product design, pricing strategies, and outreach campaigns.

- It reveals regional, ethnic, and generational differences in attitudes that are essential for localized intervention planning.

- The questionnaire is available in Nepali and can be adapted for school surveys, municipal assessments, or NGO projects.

For international actors:

- The research demonstrates a replicable, ethical field methodology that balances qualitative insight with statistically relevant sampling.

- It offers a template for conducting culturally sensitive research in diverse, low-income settings.

- Key insights can guide similar product development, health education, and behavior change interventions globally.

Instructions for practitioners:

- Use the attached PDFs as templates for conducting your own baseline studies.

- Adapt the questions to reflect your region’s cultural and product context.

- Leverage the findings to avoid common pitfalls, such as overestimating awareness of biodegradable products or underestimating positive views on restrictions.

- Use the structure to co-design products and testing tools that truly reflect end-user needs.

Enabling factors

- Long-term engagement of NIDISI, a NGO with operational presence in Nepal, enabled trust-based access to diverse communities across the country.

- Partnerships with local NGOs in regions where NIDISI does not operate directly were essential to extend geographic reach. In Humla, one of Nepal’s most remote districts, the entire research process was carried out by a trusted partner organization.

- Pre-research networking and stakeholder consultations helped NIDISI refine research tools, adapt to local realities, and align with the expectations of communities and local actors.

- Research assistants were female community members selected through NIDISI’s existing grassroots networks and recommendations from NGO partners, ensuring cultural sensitivity, linguistic fluency, and local acceptance.

- Field research relied on ethically approved, pre-tested questionnaires, with interviews conducted in multiple local languages to ensure inclusivity and clarity.

- Interviews were conducted face-to-face and door-to-door, prioritizing trust and participant comfort in culturally appropriate ways.

- The study included a demographically diverse sample, representing various ethnic, educational, religious, and economic groups, strengthening the representativeness and replicability of the findings.

- Academic collaboration with Universidade Fernando Pessoa (Portugal), where the research formed part of a Master's thesis by a NIDISI team member, ensuring methodological rigor and peer-reviewed oversight.

Lesson learned

- Language and cultural barriers can compromise data accuracy; working with local female facilitators from the same communities was essential to ensure comprehension, trust, and openness.

- Social desirability bias limited the honesty of some responses around menstrual stigma. Conducting interviews privately and individually helped mitigate this, especially when discussing taboos or product usage.

- The combination of quantitative surveys with qualitative methods (open-ended questions, observations, respondent quotes) enriched the dataset and provided both measurable and narrative insights.

- Flexibility in logistics was crucial. Travel difficulties, seasonal factors, and participant availability—especially in rural and remote areas—required adaptable timelines and contingency planning.

- Respecting local customs and religious norms throughout the research process was vital for ethical engagement and long-term acceptance of the project.

- Training research assistants thoroughly not only on tools, but also on the ethical handling of sensitive topics, significantly improved the reliability and consistency of data collected.

- Some communities initially associated the topic of menstruation with shame or discomfort, and pre-engagement through trusted local NGOs helped build the trust necessary for participation.

- Pilot-testing the questionnaire revealed linguistic ambiguities and culturally inappropriate phrasing, which were corrected before full deployment—this step proved indispensable.

- Remote districts such as Humla required an alternative model: relying fully on local NGO partners for data collection proved both effective and necessary for reaching hard-to-access populations without an extensive budget burden.

- Participant fatigue occasionally affected the quality of responses in longer interviews; reducing the number of questions and improving flow would significantly improve participant engagement.

- Engaging with younger respondents, especially adolescents, required different communication strategies and levels of explanation than with older adults. Age-sensitive adaptation improved both participation and data depth.

- Documentation and data organization during fieldwork (e.g. daily debriefs, note-taking, photo documentation, secure backups) was essential for maintaining data quality and enabling follow-up analysis.

Resources

From Insights to Innovation: R&D, Design and Prototyping

This building block captures the iterative process of translating user insights into tangible menstrual pad prototypes. Guided by the national field research (Building Block 1), Sparśa developed and tested multiple pad designs to balance absorbency, retention, comfort, hygiene, and compostability.

The process took place in two phases:

Phase 1 – Manual prototyping (pre-factory):

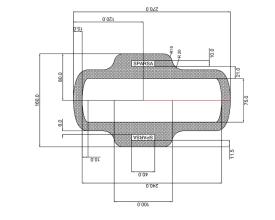

Before the factory was operational, pads were manually assembled to explore different material combinations and layering systems. Prototypes tested 3–5 layers, usually including a soft top sheet, transfer layer, absorbent core, biobased SAP (super absorbent polymer), and a compostable back sheet. Materials such as non-woven viscose, non-woven cotton, banana fibre, CMC (carboxymethyl cellulose), guar gum, sodium alginate, banana paper, biodegradable films, and glue were evaluated.

Key findings showed that while achieving high total absorbency was relatively easy — Sparśa pads even outperformed some conventional pads in total immersion tests — the main challenge lay in retention under pressure. Conventional pads use plastic hydrophobic topsheets that allow one-way fluid flow. Compostable alternatives like viscose or cotton are hydrophilic, risking surface wetness. Prototyping revealed the need to accelerate liquid transfer into the core to keep the top layer comfortable and dry.

Phase 2 – Machine-based prototyping (factory):

Once machinery was installed, a new round of prototyping began. Manual results provided guidance but could not be replicated exactly, as machine-made pads follow different assembly processes. Techniques such as embossing, ultrasonic sealing, and precise glue application were tested, alongside strict bioburden control protocols in the fibre factory.

Machine-made prototypes were systematically tested for absorption, retention, and bacterial counts. Internal testing protocols were developed in-house and then verified through certified laboratories. Initial results showed that bacterial loads varied significantly depending on fibre processing steps (e.g. cooking or beating order), underlining the importance of strict hygiene control.

Iterative design cycles combined laboratory testing with user comfort feedback, allowing continuous adjustments. By gradually refining layer combinations, thickness, and bonding methods, Sparśa optimized the balance between performance, hygiene, and environmental sustainability.

Annexes include PDFs with detailed prototype designs, retention test data, and bacterial count results. These resources are provided for practitioners who wish to replicate or adapt the methodology.

Enabling factors

- Continuous prototyping and testing cycles, allowing evidence-based refinement.

- Close collaboration between fibre and pad factories to align material treatment and hygiene protocols.

- Market analysis of competitor pads to benchmark performance and identify gaps.

- Access to internal and external testing facilities for thorough evaluation.

- Proactive implementation of hygiene protocols, including documented bioburden control steps.

- A multidisciplinary team (engineers, product designers, social researchers) ensuring both technical and social dimensions were considered.

Lesson learned

- Always validate embossing and bonding designs in real production settings — small design flaws can lead to leakage.

- Top-layer materials should never be chosen based on visual or tactile feel alone; their hydrophilic/hydrophobic behaviour must be tested under liquid.

- Avoid bulk purchasing untested materials — small pilot orders are crucial for cost efficiency and learning.

- Evaluate how liquid spreads across the entire pad geometry; otherwise, edge leakage (e.g. wings) can go unnoticed.

- Develop internal lab protocols early to identify flaws before costly mass production.

- Hygiene consistency is non-negotiable; contamination in one facility can compromise the entire production chain.

- Testing pad layers separately for bacterial load helps identify the exact source of contamination.

- Document every change in fibre treatment — minor process tweaks (e.g. cooking order) can significantly influence bacterial count.

- Different bonding methods (glue, pressure, perforation) behave differently depending on the layer’s role; trial and comparison are indispensable.

- Never rely on one successful prototype — repeatability and consistency matter more than one-off results.

Quality Assurance: Absorbency, Retention and Hygiene Compliance

This building block ensures that menstrual pads are not only functional, but also safe, hygienic, and compliant with health standards before reaching users. Pads are used on a highly sensitive part of the body, which makes strict quality assurance indispensable.

In Nepal, a sanitary pad standard exists but is not yet mandatory. Sparśa therefore chose to voluntarily design and test pads according to both national standards and international ISO-based procedures, ensuring user safety and long-term readiness for certification.

The quality assurance process is divided into two components:

1. Internal testing protocols

Developed in-house to support R&D, these tests measure:

- Total absorbency (immersion tests to measure overall liquid capacity).

- Retention under pressure (ability of the pad to hold liquid without leakage).

- Spreading behaviour (how liquid distributes across layers and wings).

- Bacterial load per layer (testing the core, topsheet, and wings separately to identify contamination sources).

These protocols allowed Sparśa to compare prototypes quickly and identify flaws before moving to external certification.

2. Standard certification testing

Once prototypes reached consistent performance, pads were tested in certified laboratories. Local labs in Nepal were prioritised for practicality, but benchmarked against ISO methods. External testing covered:

- Absorbency

- Retention

- Hygiene and microbial load

- Physical safety parameters

Since Sparśa uses natural fibres like banana fibre, viscose, and cotton, maintaining hygiene standards is even more critical than with synthetic pads. Natural fibres are compostable and environmentally preferable but can be more prone to bacterial growth if hygiene controls lapse. To address this, strict bioburden protocols were introduced: glove use at critical points (e.g. after fibre cooking), clean-room practices for pad assembly, and systematic bacterial count documentation.

Certification is not only a compliance requirement but also a trust-building tool — with users, health authorities, and donors — providing transparency and credibility in a sensitive sector.

Annexes include Nepal’s sanitary pad standards, Sparśa’s internal testing protocols, and hygiene guidelines, enabling practitioners to replicate the approach in other contexts.

Enabling factors

- Early identification of certified labs aligned with Nepal Standards and ISO procedures.

- Prioritisation of local labs for easier communication, logistics, and lower costs.

- Proactive lab visits before selection to build trust and transparency.

- Development of strong internal lab capacity to run pre-certification tests.

- Official documentation of results to validate hygiene and safety claims.

- Clear hygiene SOPs shared across both fibre and pad factories to ensure consistency.

Lesson learned

- Close communication with lab teams is essential; otherwise, valuable feedback may be lost.

- Labs test only predefined parameters — additional performance feedback must be requested.

- Aligning internal protocols with certification methods early avoids discrepancies later.

- Testing pad layers separately for bacterial counts helps identify contamination sources.

- Hygiene lapses in one production step can compromise the entire product. Consistency is key.

- Natural fibres require stricter hygiene protocols than plastics, making bioburden control vital for compostable pads.

- Small producers should prioritise three core tests: absorbency, retention, and microbial load. These are the minimum standards for safe product development.

- Frequent small-batch testing is more effective and cost-efficient than infrequent large-scale tests.

- Certification should be seen as part of a continuous improvement cycle, not a final step. It strengthens user trust, supports market acceptance, and ensures product credibility.

Next Steps: Feedback Based Optimization for outcome-oriented Decisions

Product development does not end with certification. To create menstrual pads that are accepted, trusted, and widely adopted, Sparśa built a structured system to integrate real user experiences into design improvements.

This building block focuses on user feedback surveys and community-based testing of Sparśa pads. The initial questionnaire was co-designed by the team and adapted from international tools, but simplified after field trials revealed that long, technical questions discouraged participation. The refined survey is short, available in both Nepali and English, and structured around everyday experiences of menstruation.

The survey collects both quantitative data (absorbency, leakage, comfort, ease of movement, wearability) and qualitative insights (likes, dislikes, suggestions). It also includes questions about packaging, clarity of information, and first impressions. Importantly, the survey is distributed through Google Forms for easy access and rapid data analysis, but also adapted for offline use where internet is unavailable.

The next stage is scaling up to at least 300 users, ensuring diverse representation across age, geography, and socioeconomic background. By triangulating lab results (Block 3) with user feedback, Sparśa can continuously optimize pad design, packaging, and distribution strategies.

This approach demonstrates that menstrual product development is not only about technical performance, but also about cultural acceptability, dignity, and user trust.

Enabling factors

- Translation of the questionnaire into local languages and simplification of terminology.

- Structured design linking questions to real-life scenarios (e.g. school, work, travel).

- Collaboration with schools, NGOs, and local women’s groups to distribute surveys and encourage participation.

- Use of digital tools (Google Forms) for efficient data collection and analysis.

- Flexibility to adapt tools for both online and offline contexts.

Lesson learned

- Avoiding complex terminology is essential; many Nepali girls did not understand technical menstrual health vocabulary.

- Long and complicated questions reduce participation; short and clear formats improve accuracy.

- Feedback methods should be tested in small pilots before full deployment.

- User feedback is most reliable when anonymity is respected — especially for adolescents.

- A dual-language approach (Nepali + English) increases inclusivity and widens data use for local and international partners.

- Surveys should capture not just performance data, but also perceptions and feelings, which strongly influence adoption.

- Continuous feedback collection allows for incremental improvements rather than costly redesigns later.

- Packaging feedback is as important as product feedback, since first impressions influence user trust.

Impacts

The solution has created measurable environmental, social, and economic impacts in Nepal. Environmentally, Sparśa pads offer a compostable alternative to the dominant plastic-based products, directly reducing long-term waste and raising awareness on sustainable menstrual choices. By piloting banana fibre and other natural materials, the project demonstrates viable pathways for local, plastic-free product innovation.

Socially, the project has advanced menstrual health and dignity by ensuring that pad design is informed by users themselves. More than 820 women and girls across 14 districts contributed insights that shaped prototypes, testing, and feedback surveys. This has broken taboos around menstruation, encouraged open discussion, and helped women adopt safer practices. Feedback loops also empower users to influence product development, increasing ownership and trust.

Economically, the initiative strengthens local value chains by sourcing fibres in Nepal, training technical staff, and developing internal testing capacities. It reduces dependency on imports while laying the groundwork for a financially sustainable, socially owned enterprise that can be replicated in other regions.

Beneficiaries

Direct beneficiaries include Nepali women and girls accessing safer, compostable pads. Indirectly, local communities, schools, and health systems benefit through reduced waste, improved menstrual health, and strengthened local production capacities.

Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF)

Sustainable Development Goals

Story

When Sparśa carried out a nationwide survey on menstrual product use and stigma, we met Tilsari, a 19-year-old student from Jogbudha Village in Dadeldhura District, far-western Nepal. This remote region is one of the strongholds of Chhaupadi—the practice of isolating menstruating women in sheds.

At the time, Tilsari had just moved from her inaccessible home village to Jogbudha to pursue higher education, as her village had no roads or health centre. She became one of our two local research assistants, carrying out dozens of interviews in her community about product use, stigma, and taboos. Until two years earlier, she herself had practiced Chhaupadi. She recalled nights spent in sheds far from her family home, feeling safe only if other girls were there too. After government campaigns demolished many sheds, women were left worse off—sleeping outside or in dark, animal stalls. “Unless Chhaupadi is destroyed in the mindset of people,” she said, “nothing will truly change.”

Participating in the research transformed Tilsari. She gained confidence, began engaging in community volunteering, and even spoke on the local radio about menstrual stigma and other social challenges. To our great surprise, when we spoke with local women about menstruation, they were not timid or ashamed. Instead, they were openly rebellious—expressing how much they hated Chhaupadi and how grateful they were that, for the first time, someone was listening to them. “Nobody ever asked us about menstruation before,” they told us. They felt seen.

Tilsari’s involvement—and that of other local girls—sparked lasting change. Their confidence to speak out helped shift community attitudes, and women who once felt silenced began to take ownership of their voices. Today, Tilsari has completed her Bachelor’s in Business Studies and, while preparing for civil service exams, continues to support her mother and engage in community life. She recently shared that Chhaupadi is no longer practiced in her village.

Her story shows how involving young women directly in research not only generates better data, but also empowers them as agents of change. The research process helped local girls build confidence and continue working with others to shift community norms around menstruation.