Conservation inclusive grâce à l'apprentissage social dans les zones protégées de l'Alaska

La région de Denali, à l'intérieur de l'Alaska, est confrontée à des pressions sociales et environnementales liées à l'évolution rapide du paysage. Bien que les communautés de cette région soient très unies et liées par leur attachement commun à la région, les acteurs locaux peuvent se sentir exclus du processus décisionnel régional concernant les questions de gestion des ressources. L'une des voies possibles vers une prise de décision plus inclusive consiste à faire en sorte que les résidents apprennent les uns des autres et s'adaptent les uns aux autres dans le cadre des discussions sur l'évolution du paysage, renforçant ainsi les voix sous-représentées par le biais d'un renforcement des connaissances collectives. La délibération communautaire peut être difficile à mettre en place, mais l'apprentissage social est un outil de conservation qui peut faciliter le dialogue partagé basé sur la compréhension des nombreuses et diverses valeurs liées à la gestion des terres publiques par le biais de la délibération communautaire. Cette solution est basée sur le concept de conservation socialement inclusive, qui vise à représenter la façon dont les gens valorisent la nature afin d'améliorer la gestion des zones protégées.

Contexte

Défis à relever

Notre solution vise à relever les défis environnementaux, sociaux et économiques interdépendants de la région de Denali. Parmi ces défis figurent la modification des régimes météorologiques et climatiques due au changement climatique, l'augmentation du risque d'incendie de forêt due au dendroctone de l'épicéa(Dendroctonus rufipennis) et les préoccupations concernant la meilleure façon de préserver les caractéristiques uniques du paysage de Denali, telles que la solitude, le paysage sonore et les vastes étendues accidentées, pour les générations futures. Des tensions et un manque de communication existent souvent entre certains groupes de parties prenantes. En conséquence, certains résidents ont exprimé leur frustration face à l'absence de représentation significative des différentes voix dans le processus décisionnel public. Le tourisme industriel est l'un des principaux défis économiques, car il apporte des emplois et la possibilité de maintenir des moyens de subsistance dans un paysage rural, tout en axant le développement sur l'accueil des visiteurs plutôt que sur la préservation des caractéristiques du paysage appréciées par les habitants de la région.

Emplacement

Traiter

Résumé du processus

Cette solution met en évidence l'importance d'établir des relations et une compréhension collective au fil du temps afin de soutenir une prise de décision inclusive sur la gestion des zones protégées. Les éléments constitutifs de la région de Denali, à l'intérieur de l'Alaska, représentent un processus itératif, où chaque étape s'appuie sur la précédente. Les moyens et les objectifs du projet consistent à faciliter les délibérations de la communauté sur la gestion des zones protégées et à identifier les points d'alignement ou de désalignement dans les divers points de vue des parties prenantes. Cependant, l'intégration de ces différentes compréhensions des parties prenantes dans le savoir collectif pour la conservation de la région de Denali et au-delà devient alors une nouvelle base, à partir de laquelle développer de futurs partenariats et le renforcement des capacités.

Blocs de construction

Construire des partenariats locaux

Les habitants de la région de Denali sont liés par leur appréciation commune du paysage, ce qui donne lieu à des communautés très unies. Pour que le projet aboutisse, il était important que l'équipe de recherche établisse une compréhension et une confiance mutuelles fondées sur des partenariats locaux. Ces relations ont permis d'ancrer le projet dans un contexte pertinent et régional, de comprendre ce qui compte le plus pour les habitants de la région et d'orienter les différentes phases du projet :

- Un comité exécutif local composé de dix parties prenantes représentant une diversité de points de vue de la région a été formé pour établir des partenariats locaux.

- Le projet a engagé un habitant de la région comme technicien de recherche et défenseur de la communauté pour le projet, afin d'aider à la collecte et à la saisie des données, à la conception du projet, à la diffusion de l'information et à la communication des résultats de la recherche.

- Une série d'entretiens informels et de séances d'écoute ont été organisés afin d'entamer le processus de création d'une compréhension commune du changement dans la région de Denali.

Facteurs favorables

Le temps et l'engagement des représentants du projet ont été essentiels pour faire de l'établissement de partenariats un processus actif. En outre, les chefs d'équipe avaient déjà mené des recherches dans la région et noué plusieurs relations qui témoignaient de leurs liens avec la région, ainsi que de leurs investissements à long terme dans la facilitation des discussions sur la modification du paysage.

Leçon apprise

On ne saurait trop insister sur l'importance du temps, de l'attention et du soutien qui sont consacrés à l'établissement et au maintien des partenariats. Les relations nouées au début du projet doivent être entretenues en permanence et ne peuvent pas être considérées comme une simple "coche". Pour établir des partenariats, il faut également être sensible et réceptif aux "saisons" de l'année des populations locales, par exemple, ne pas demander à se réunir trop souvent lorsque la période de chasse ou de récolte est chargée, même si cela ne correspond pas aux périodes chargées de l'année universitaire ou de l'année de gestion. En outre, les efforts visant à instaurer un climat de confiance avec les différentes communautés doivent également être abordés avec des stratégies variées. Par exemple, une chose aussi simple que d'acheter une tasse de café dans une entreprise locale démontre la réciprocité et l'investissement dans le bien-être de la communauté.

Comprendre le lieu

Afin d'approfondir la compréhension des différents points de vue dans la région de Denali, ce projet s'est concentré sur l'engagement de diverses parties prenantes dans des discussions sur les caractéristiques de la région et sur la façon dont elle est gérée. Nous avons utilisé des entretiens semi-structurés et des groupes de discussion. Les entretiens avec les résidents comprenaient des questions sur le sentiment d'appartenance, la perception de l'évolution du paysage, les organisations locales, la connaissance du paysage et la gouvernance. Les participants ont été identifiés au cours de la première phase de cette étude et une approche d'échantillonnage en boule de neige a été adoptée, les participants étant invités à nommer d'autres personnes.

Cette phase a également permis d'identifier les perceptions des habitants de la région en tant que système socio-écologique afin de comprendre comment les communautés anticipent le changement et de jeter les bases d'une gestion collaborative qui donne la priorité à la résilience socio-écologique. Ce projet a adopté la cartographie cognitive floue, un outil participatif utilisé pour représenter graphiquement l'image mentale qu'ont les habitants de leur lieu de vie et de la façon dont les choses sont liées les unes aux autres. Cette approche a permis aux habitants de cartographier leurs perceptions des principales caractéristiques de la région et des facteurs de changement. L'exercice individuel a été réalisé au cours d'une série de groupes de discussion et d'entretiens, ce qui a permis de produire 51 cartes qui ont été agrégées pour représenter une perspective régionale.

Facteurs favorables

Le principal facteur favorable a été le travail antérieur basé sur l'établissement de relations, de confiance et de partenariats locaux. Avant la collecte des données, les habitants ont été invités à participer à des réunions informelles pour se présenter et discuter du projet. Les habitants qui se sont engagés dans des conversations informelles ont été invités à participer à la collecte formelle de données. Les conversations initiales ont permis aux habitants de se familiariser avec le projet et ont favorisé la confiance avec les chercheurs. Les habitants n'avaient jamais participé à des exercices de cartographie auparavant et ont apprécié la facilitation.

Leçon apprise

La participation des résidents à des entretiens semi-structurés et à des exercices de cartographie cognitive floue a permis de comprendre en profondeur l'histoire, les connaissances, les perceptions et les liens avec le lieu des diverses parties prenantes, qui ont pu être modélisés pour anticiper les visions souhaitées pour l'avenir. Cette phase du processus de recherche a permis de continuer à établir des relations avec les parties prenantes locales - en partageant et en ouvrant la discussion sur les cartes communautaires avec le comité exécutif local et les communautés de Denali - et d'informer la conception des phases quantitatives ultérieures de la collecte de données. En outre, les exercices de cartographie cognitive floue ont permis de comprendre la région de Denali en tant que système socio-écologique tel qu'il est défini par les résidents. Pour mieux interpréter les résultats des cartes cognitives floues, il est recommandé de collecter et d'analyser les données qualitatives issues des groupes de discussion ou des entretiens. Ces résultats peuvent élucider les synergies et les lacunes dans la façon dont les différents groupes d'acteurs comprennent la région, ce qui est utile pour développer des stratégies de communication et des approches participatives afin d'impliquer les résidents dans la planification future de la région.

Vision pour l'avenir de la région de Denali

L'objectif de l'élaboration d'une vision pour l'avenir de la région de Denali est d'évaluer les préférences des parties prenantes et les compromis qu'elles sont prêtes à faire lorsqu'elles réfléchissent à l'avenir de la région. Il est important d'identifier des visions distinctes pour l'avenir dans des endroits comme l'Alaska intérieur, où les impacts du changement climatique sont amplifiés et où l'on s'attend à ce qu'ils transforment rapidement le paysage socio-écologique. Ces informations peuvent renseigner les décideurs sur les priorités pour l'avenir d'un large éventail de parties prenantes et servir de base à une planification participative. Cette étude a évalué les visions dans le cadre d'une enquête en mode mixte menée auprès des habitants de la région de Denali.

Afin d'identifier les préférences et les compromis pour les conditions futures, une expérience de choix discret a été réalisée pour évaluer les forces des préférences et des compromis pour les conditions futures de la région de Denali. Des données d'enquête ont été utilisées pour comprendre les préférences pour des attributs tels que les populations d'animaux sauvages, le tourisme hors saison et la gestion des incendies, ainsi que le coût du maintien des conditions actuelles de ces attributs. Les résultats ont montré que tous ces facteurs influençaient les préférences pour l'avenir et que l'éventail des attitudes environnementales des groupes de parties prenantes expliquait la variation de la force des préférences déclarées par les répondants à l'enquête.

Facteurs favorables

Les travaux antérieurs qui ont évalué qualitativement les perceptions des résidents sur les changements du paysage et les connaissances ont joué un rôle déterminant dans le succès de ce bloc de construction. En particulier, une compréhension approfondie des caractéristiques pertinentes du paysage a été développée avant d'élaborer les paramètres de notre expérience de choix discret. La collecte de données de tests pilotes a également été importante pour affiner le langage utilisé dans notre enquête et l'éventail des changements considérés comme des conditions futures réalistes dans la région.

Leçon apprise

L'évaluation des préférences des habitants concernant les conditions futures du paysage et les compromis qu'ils sont prêts à faire lorsqu'ils réfléchissent à l'avenir a permis de recueillir des informations importantes sur les priorités des habitants. Il s'agit d'une information cruciale pour les décideurs, car elle leur permet de répondre plus efficacement aux besoins de leurs administrés. L'élaboration de ce module a également permis de tirer des enseignements sur la valeur des stratégies créatives et mixtes de collecte de données, qui augmentent la probabilité que l'échantillon final reflète des points de vue diversifiés. Dans l'ensemble, la collaboration avec les acteurs locaux pour comprendre les visions de l'avenir a permis de générer des données empiriques montrant l'importance relative des caractéristiques qui décrivent le paysage de Denali. Les résultats sont également utiles pour anticiper le soutien ou la résistance des résidents aux changements dans les visions de l'avenir, de manière à aider les décideurs à comprendre les points de vue des différentes parties prenantes.

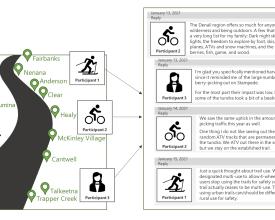

L'apprentissage par la délibération communautaire

L'objectif de la délibération communautaire est de faciliter le processus d'apprentissage social des résidents en matière de gestion des zones protégées par le biais de discussions menées par les parties prenantes. L'apprentissage social est le changement de compréhension qui se produit parmi les individus et les groupes par le biais d'interactions sociales. Un certain nombre d'approches participatives peuvent être adoptées pour faciliter l'apprentissage social ; nous avons utilisé la délibération communautaire par le biais d'un forum de discussion en ligne. Le forum de discussion en ligne comprenait une activité de quatre semaines à laquelle les résidents ont participé de manière asynchrone. Les résidents ont reçu un nouveau sujet à traiter chaque semaine et ont été encouragés à se concentrer sur les réponses aux commentaires laissés par les autres résidents. Des résumés hebdomadaires ont été produits et des commentaires ont été demandés pour s'assurer que les résumés reflétaient bien les délibérations des résidents. Plus de 400 réponses et commentaires ont été postés par 37 résidents sur le forum de discussion tout au long des quatre semaines. La dernière question demandait aux résidents ce qu'ils avaient appris en participant au forum, suivie d'un questionnaire d'enquête administré en ligne pour mesurer d'autres changements de valeurs, de perceptions ou de comportements résultant de la participation.

Facteurs favorables

Les travaux antérieurs basés sur l'établissement de relations dans la région ont été importants pour la participation, en particulier les séances d'écoute et l'établissement de partenariats locaux. Les habitants ont été rémunérés pour leur temps, positionnés en tant qu'experts à qui l'on a demandé de démontrer leurs connaissances locales, et organisés en trois petits groupes de discussion pour encourager les interactions personnalisées. En outre, l'équipe de recherche a demandé un retour d'information sur l'interprétation des résultats afin d'accroître l'appropriation du projet.

Leçon apprise

Les résidents locaux ont aimé participer à la discussion en ligne et ont apprécié d'en apprendre davantage sur le paysage et la gestion des zones protégées. L'attitude positive de l'équipe de recherche a favorisé le processus d'apprentissage en instaurant un dialogue constructif sur les lieux de la région de Denali. Il était également important de maintenir une certaine souplesse dans l'approche de la recherche afin de favoriser la participation d'un plus grand nombre de résidents au sein d'un paysage rural. Par exemple, certaines personnes ont choisi de participer de manière anonyme pour limiter les risques, tandis que d'autres ont donné leur nom et ont apprécié de connaître certaines des personnes de leur groupe. Des groupes de discussion ont été organisés au début du forum afin de fournir des conseils personnalisés sur l'objectif du forum et de faire démarrer les choses, suivis de la discussion asynchrone. Certains participants ont exprimé leur intérêt pour des réunions répétées en plus de la composante de discussion en ligne. Dans l'ensemble, nous suggérons qu'un mélange de stratégies d'engagement en ligne, en personne et hybrides fonctionne le mieux pour saisir l'éventail des préférences en matière de participation.

Ressources

Période de réflexion et intégration des résultats

L'objectif de la période de réflexion et de l'intégration des résultats du projet est de diffuser en permanence les conclusions de cette recherche auprès des habitants, des entreprises, des agences gouvernementales, des scientifiques et des autres décideurs concernés qui façonnent l'avenir des zones protégées, notamment dans la région de Denali. À son tour, l'équipe de recherche acquiert des connaissances sur la façon dont les habitants discutent et réagissent aux pressions liées à l'évolution rapide de la société, de l'économie et du paysage, et ces connaissances sont communiquées aux parties prenantes. Ce processus cyclique de co-création se déroule tout au long du projet. Le support de réflexion prend diverses formes, notamment des webinaires, des discussions approfondies avec le comité exécutif local et des rapports fournis aux décideurs. La période de réflexion aboutira à la réalisation d'un film sur les communautés de la région de Denali, ainsi qu'à des ateliers de synthèse à la fin du projet. Ces ateliers sont conçus comme des espaces de découverte civique permettant aux habitants de prendre conscience des différentes valeurs qu'ils partagent (ou non) avec d'autres habitants de la région en ce qui concerne les lieux. Ils sont encouragés à reconnaître les opportunités potentielles de croissance de manière à tirer parti d'une pensée partagée, d'actions dirigées et d'un soutien canalisé pour préserver le caractère souhaité des lieux.

Facteurs favorables

Toutes les phases précédentes de ce projet contribuent à soutenir cet élément de base. Les bases de données de méthodes mixtes de ce projet fournissent la base empirique pour l'engagement et la réflexion sur les leçons tirées du processus de recherche. Les relations existantes entre les différentes parties prenantes sont également importantes pour encourager la participation et maximiser l'impact de l'étude.

Leçon apprise

Les principaux enseignements tirés de ce projet sont les suivants (1) L'instauration de la confiance est un ensemble d'actions permanentes qui nécessite une attention constante. (2) Il existe une tendance à remplacer la dichotomie utilisation/préservation par la complexité de la durabilité environnementale, du tourisme industriel et de l'évolution du paysage. (3) Pour tracer la voie d'une conservation inclusive, il faudra comprendre les processus qui réduisent les tensions entre les groupes de parties prenantes. (4) S'éloigner du conflit généralisé pour clarifier les points de conflit spécifiques et apprécier les points d'accord.

Impacts

Cette solution a permis de mettre en relation des membres de la communauté et des acteurs locaux issus de divers groupes d'intérêt de la région de Denali. L'établissement de partenariats locaux permet d'identifier les besoins des personnes vivant dans la région et de rechercher les orientations les plus significatives pour les résidents. Comprendre les liens entre les habitants et le paysage de Denali est la deuxième étape essentielle de la solution, qui permet d'instaurer un climat de confiance et une compréhension commune au sein d'une communauté soudée qui se méfie des nouveaux arrivants ou des résidents temporaires qui n'aiment pas intimement la région ou ne la comprennent pas comme eux. Les activités, telles qu'une enquête sur la vision de l'avenir de la région, mettent en évidence les principaux compromis que les gens font pour s'adapter à l'évolution du paysage, l'importance des valeurs multiples pour prédire l'engagement dans les activités d'intendance, et le rôle de la confiance dans la perception de l'inclusivité par les résidents. L 'apprentissage social par le biais des délibérations communautaires permet également aux habitants d'acquérir des connaissances sur les différents points de vue et de nouer des relations précieuses afin d'accroître la capacité de la communauté à s'engager dans la prise de décision régionale. Les résultats interconnectés des éléments constitutifs sont continuellement réintégrés dans la compréhension collective de la région de Denali par le biais de webinaires, d'ateliers et de réunions avec des responsables gouvernementaux et industriels.

Bénéficiaires

Le projet vise à renforcer l'engagement au sein et entre les résidents, les entreprises, les agences gouvernementales et les autres décideurs qui façonnent l'avenir de la région. La communauté scientifique est également un public cible clé de cette recherche.

Objectifs de développement durable

Histoire

Les solutions sont un voyage. Le projet ENVISION a permis à des habitants de partager leurs liens avec l'environnement local et de s'ouvrir aux défis que pose la gestion des ressources à divers groupes d'intérêt. Nous avons lancé ce projet pour comprendre les perspectives des habitants des environs du parc national et de la réserve de Denali et du parc d'État de Denali en Alaska, mais nous n'avions pas pleinement mesuré les difficultés liées à des conversations approfondies sur des sujets qui étaient au cœur de l'identité et de l'héritage des gens, et qui étaient imprégnés des expériences vécues d'une histoire controversée. Lors de notre premier groupe de discussion, nous nous sommes rendus dans le village autochtone de Cantwell pour découvrir les relations notoirement mitigées que les résidents entretenaient avec les agences de gestion des terres avoisinantes. Notre présence a été accueillie avec résistance par ceux qui s'étaient déjà sentis trahis par les événements de participation publique. Ces habitants ont passé plus de deux heures à faire part de leurs frustrations face à ce qui leur paraissait être une sensibilisation plus malhonnête ; ils se sont inquiétés du fait que toutes les voix n'avaient pas été entendues dans le passé et que les politiques d'aménagement du territoire ne représentaient souvent pas l'ensemble de la population, y compris les Autochtones d'Alaska. Après cet événement, nous avons consacré les semaines suivantes à nouer des relations avec ces personnes et à discuter de leurs préoccupations. À la fin de notre visite, les participants se sont sentis suffisamment à l'aise pour nous parler ouvertement de leurs valeurs, dans l'espoir que notre projet leur permette de communiquer plus directement avec les décideurs. Cette expérience nous a permis d'apprécier la complexité des relations historiques profondément ancrées entre les gens et les lieux, ainsi que la nécessité d'un dialogue ouvert pour comprendre comment les résidents réagissent aux agences qui gèrent les terres publiques en Alaska. Au cours des deux années suivantes, notre processus de recherche comprenant des sessions d'écoute, des enquêtes et des ateliers de planification a été ouvert à ces évaluations honnêtes (bien que difficiles) des conflits liés à la modification des paysages, étant donné leur capacité à construire une conversation constructive fondée sur l'appréciation et le respect des autres. Le projet ENVISION continue d'œuvrer pour une meilleure compréhension et une meilleure communication des divers intérêts et de la manière dont ils sont (ou ne sont pas) représentés dans les politiques environnementales. L'ensemble des actions adoptées dans le cadre de notre recherche constitue ainsi un guide pour toutes les parties prenantes - y compris les habitants, les scientifiques et les agences de gestion des ressources - dans leur démarche de co-création de solutions de conservation inclusives dans la région de Denali, en Alaska (États-Unis).