This building block provides the essential spatial intelligence for PyroSense, enabling a dynamic understanding of the geographical landscape. Its core purpose is to identify fire risk areas, pinpoint incident locations, and visualize resource deployment. This is crucial for strategic decision-making, allowing proactive resource allocation, and response planning.

PyroSense utilizes a robust Geographic Information System (GIS) to power this function. The GIS integrates various spatial data layers, including topography, vegetation, infrastructure, etc. Initially, baseline risk maps are created by analyzing factors, guiding the placement of sensors and cameras.

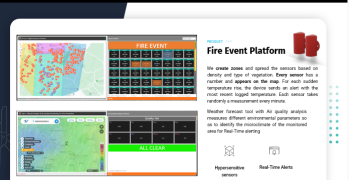

Upon detection of a potential fire by environmental sensors or AI, the system immediately feeds the precise coordinates into the GIS. This real-time location data, combined with meteorological data (local and satellite), enables dynamic risk assessments. The GIS also serves as a central operational dashboard, visualizing the real-time positions of all deployed assets, including drones and first responder teams. This facilitates optimal resource allocation and coordination. This critical information is then communicated via a web application to stakeholders, providing clear visual situational awareness and supporting informed decision-making.

The accuracy and utility of geospatial planning are directly proportional to the quality and timeliness of the underlying GIS data. Investing in high-resolution, frequently updated maps and environmental data is paramount. Furthermore, the ability to integrate real-time sensor and drone data into the GIS for dynamic risk assessment proved to be a game-changer, moving beyond static planning to predictive capabilities.

Initial challenges included the significant effort required to collect and digitize comprehensive baseline GIS data for large, remote areas. Data standardization across different sources (e.g., various government agencies, local surveys) was also a hurdle. Additionally, ensuring the GIS platform could handle the computational load of real-time data fusion and complex fire spread simulations without latency issues was a technical challenge.

- Before deployment, dedicate substantial resources to acquiring and standardizing all relevant geospatial data.

- Choose a GIS platform that can scale with increasing data volumes and computational demands.

- Ensure that local teams are proficient in using the GIS platform