Donner aux communautés locales les moyens de gérer la pêche artisanale

Cette solution adopte une double approche ascendante et descendante de la gestion des ressources marines locales dans un réseau de 26 réserves marines. Elle a développé un plan de cogestion de la pêche côtière à l'échelle de l'océan, offrant une reconnaissance nationale formelle des droits des pêcheurs locaux et des conventions sociales coutumières (dina) entre les communautés de pêcheurs. Les pêcheurs ont reçu des ressources pour faire appliquer les règlements et les dina afin d'accroître leur rôle dans la gestion des ressources marines et de compenser le manque de ressources des agences gouvernementales.

Contexte

Défis à relever

- Absence de sentiment de propriété et de reconnaissance juridique

- 100 000 personnes, essentiellement pauvres et rurales, dépendent des eaux riches de la baie d'Antongil pour assurer leur subsistance.

- La surexploitation due à l'augmentation de la population humaine, les pratiques de pêche destructrices et le non-respect des restrictions concernant les engins de pêche entraînent la dégradation de l'habitat côtier et des pêcheries, ainsi que la disparition des récifs coralliens et le déclin des poissons et des invertébrés.

Emplacement

Traiter

Résumé du processus

Le plan de gestion (BB 1) fournit le cadre national et est essentiel pour légitimer les rôles et les responsabilités des communautés aux yeux des décideurs du gouvernement. Il suscite également la fierté et la responsabilité des communautés locales qui ont compris que leur rôle dans la gestion des ressources naturelles était pris au sérieux. En outre, il assure la viabilité à long terme de la structure globale des droits des communautés en les inscrivant dans la législation nationale. Le dinabe (BB 2) est un processus local ascendant qui vise à renforcer l'appropriation et la compréhension de la communauté en ce qui concerne l'utilisation durable des ressources. Il s'agit d'un complément important car il est compris par les communautés et a une légitimité à leurs yeux. Il signale également au gouvernement l'engagement des communautés locales et leur volonté de jouer un rôle dans la gestion et la prise de décision. Les comités de contrôle et de surveillance (BB 3) représentent un pilier de soutien essentiel et fournissent un mécanisme d'application simple, réactif et proche qui s'appuie sur le rôle important des communautés locales en tant que premières responsables. Sans cette mise en application, la gestion et les dinas ne seraient que des rapports sur une étagère ayant une reconnaissance légale mais sans valeur réelle.

Blocs de construction

Plan de cogestion des pêches de la baie d'Antongil (ABFMP)

Le plan de co-gestion des pêcheries de la baie d'Antongil (ABFMP) est un cadre juridique national qui reconnaît les droits de gestion des communautés locales. Il a été élaboré grâce à une importante collaboration entre WCS, les utilisateurs des ressources et le gouvernement. Le résultat a été le premier plan de cogestion de la pêche traditionnelle, artisanale et industrielle à l'échelle d'un paysage marin à Madagascar, couvrant 3 746 km2 d'habitats marins, qui confère officiellement l'autorité de gestion de la pêche aux communautés locales. Le plan reconnaît le rôle des réserves marines de la baie d'Antongil dans la reconstitution des ressources et fixe des niveaux maximaux pour les efforts de pêche traditionnelle, artisanale et industrielle. Le décret d'adoption du PAGF accorde aux associations de pêcheurs le droit d'élaborer des réglementations adaptées au contexte local, d'identifier et de mettre en œuvre des mesures pratiques pour assurer le respect des réglementations, d'enregistrer et de délivrer des licences aux pêcheurs locaux, et d'établir et de faire respecter différentes zones à l'intérieur des zones de pêche gérées localement. Les associations locales de pêcheurs sont officiellement responsables de la mise en œuvre de l'ABFMP et participent activement aux activités d'inspection, de surveillance et de contrôle.

Facteurs favorables

- Consultation importante des parties prenantes sur une longue période (108 réunions, 6 ateliers, 1466 participants sur 7 mois)

- Efforts simultanés pour sensibiliser les communautés locales à la valeur sociale, économique et de conservation des ressources marines et au fonctionnement de l'écosystème, afin qu'elles disposent des informations nécessaires pour participer activement aux débats et aux discussions.

- Facilitation de la coopération entre les parties prenantes à différents niveaux par la création d'une association multipartenaires (PCDDBA) afin de fournir une plateforme d'échange et de discussion.

Leçon apprise

- Il est essentiel de veiller à ce que tous les acteurs du processus disposent des mêmes niveaux d'information et, en particulier, à ce que la communauté locale ait la capacité de s'engager activement.

- Il est nécessaire de prévoir des ressources pour l'accompagnement du processus à long terme afin de pouvoir absorber les retards inévitables tout en menant le processus à son terme.

- Il est nécessaire de gérer les attentes de la communauté et du gouvernement en ce qui concerne le temps nécessaire pour obtenir des résultats positifs de la mise en œuvre d'un tel processus.

- Une facilitation attentive du processus est nécessaire pour surmonter les barrières traditionnelles et culturelles qui créent des obstacles à la pleine participation des groupes marginaux (ménages pauvres, pêcheurs locaux, femmes, jeunes, etc.).

Le Dinabe : une convention sociale entre les communautés locales

Le dina est une convention sociale traditionnelle qui contribue à réguler la vie des communautés malgaches. Il permet aux communautés locales d'élaborer un ensemble de règles et de règlements pour régir un ensemble particulier de circonstances et est couramment utilisé dans le cadre de la gestion des ressources naturelles. Les dinas sont élaborés de manière participative et ont une valeur juridique grâce à leur homologation par les tribunaux locaux. Leur application relève de la communauté locale. Dans le cas de la baie d'Antongil, 26 dinas ont été créés - un pour chaque association de pêcheurs dans chaque réserve marine gérée localement. Les dinas comprennent

- un ensemble de règles pour les principales infractions (engins destructeurs, taille minimale des poissons, etc,)

- un ensemble de règles adaptées au contexte local (tabous, règles de pêche nocturne, etc.), et

- un ensemble de sanctions.

En plus des dinas locaux, les communautés locales des 26 réserves marines ont convenu de créer un "dinabe", qui vise à fédérer les dinas individuels et fournit un cadre global pour l'utilisation durable des ressources marines et des zones côtières de la baie, en complément du plan de gestion de l'ensemble de la baie.

Facteurs favorables

- Un processus de diffusion de l'information et d'éducation était essentiel pour s'assurer que les communautés disposaient des connaissances nécessaires pour prendre des décisions sur le contenu des dinas.

- Tout en maintenant le leadership de la communauté dans le processus, l'implication du gouvernement dès le début était importante pour minimiser le risque que des obstacles soient rencontrés plus tard dans le processus.

- La reconnaissance juridique des conventions sociales est essentielle pour leur légitimité aux yeux de la communauté et du gouvernement.

Leçon apprise

- Bien que difficile à réaliser en raison de l'absence d'un porte-parole reconnu, l'implication des pêcheurs migrants ou externes dans le processus d'élaboration du plan de gestion de l'ensemble de la baie (qui établit les principes des droits de pêche exclusifs pour les communautés locales) aurait contribué à atténuer leur influence négative sur le processus d'homologation du dinabe.

- Toutes les parties ne sont pas forcément favorables à la gestion locale des droits de pêche et des situations inattendues ou des oppositions peuvent survenir, comme ce fut le cas avec un groupe de pêcheurs extérieurs qui a bloqué l'homologation du dinabe final.

- Les relations établies au cours du processus entre toutes les parties prenantes sont un résultat tout aussi important que le plan de gestion et le dinabe et constituent une base solide pour surmonter les problèmes. Le processus d'élaboration du plan de gestion et du dinabe a créé un réseau de partenaires qui n'existait pas auparavant et qui travaille maintenant ensemble pour résoudre la question de l'homologation du dinabe.

Comité de contrôle et de surveillance (CCS)

Avec le soutien de WCS et sous la direction de l'agence gouvernementale chargée de l'application des lois sur la pêche, chaque association a mis en place un comité local de contrôle et de surveillance (CCS) composé de gardes communautaires bénévoles, officiellement reconnus par le gouvernement et munis d'un badge d'identification numéroté et enregistré. Le CCS permet l'application et la mise en œuvre des règles et règlements définis dans le plan de gestion et les dinas. Les Rangers sont équipés et formés pour effectuer des missions de surveillance et de contrôle et reçoivent une formation ciblée sur : la connaissance de la réglementation ; les méthodes de sensibilisation ; la dissuasion/sanction ; la répression ; l'enregistrement des infractions ; et la définition des stratégies et de l'organisation des missions de surveillance et de contrôle. Les Rangers sont issus de différents milieux sociaux et comprennent des hommes et des femmes, des chefs de village, des autorités traditionnelles et religieuses, des opérateurs du secteur privé, des professeurs d'école et des pêcheurs. Les CCS effectuent des missions selon des calendriers variables et en fonction des circonstances, avec des patrouilles conjointes de plusieurs associations pour couvrir de plus grandes zones ou des missions conjointes des rangers des CCS et des représentants du gouvernement chargés de l'application de la législation sur la pêche lorsque des infractions importantes sont observées.

Facteurs favorables

- La volonté du gouvernement de transférer officiellement certaines responsabilités en matière d'application de la loi aux communautés et de reconnaître officiellement le rôle des communautés locales.

- Dans les phases initiales, un partenaire technique et financier capable de fournir un soutien externe substantiel pour la mise en place, le pilotage et la mise en œuvre initiale des systèmes.

- Des communautés disposées à jouer le rôle d'agent d'exécution et à comprendre les avantages qui en résulteront.

Leçon apprise

Il est nécessaire d'envisager le financement à long terme et de mettre en place des systèmes de viabilité financière dès le début de l'élaboration du projet. De même, il est important de prévoir une autonomie technique pour les CSC afin de permettre un retrait progressif des partenaires techniques. Ces systèmes communautaires présentent de nombreux aspects positifs - proximité, flexibilité, engagement, etc. - mais il est important de s'assurer qu'ils ne sont pas développés d'une manière qui tente de dupliquer ou de remplacer le rôle réglementaire du gouvernement. Ceci est particulièrement vrai dans des situations telles que Madagascar où les agents gouvernementaux manquent cruellement de ressources et sont largement absents des activités régulières de mise en application sur le terrain. D'un point de vue pratique, les uniformes et les badges sont extrêmement importants pour donner aux rangers un statut élevé dans les communautés afin qu'ils soient respectés et pour encourager d'autres personnes à rejoindre le CCS.

Impacts

L'interdiction de la pêche à la senne de plage par le gouvernement en 2006 est un succès majeur des efforts conjoints des utilisateurs des ressources, de la WCS et du gouvernement. La région d'Analanjirofo, y compris la baie d'Antongil, est le seul endroit à Madagascar où ces engins de pêche destructeurs sont interdits par la loi. À la suite des fermetures temporaires des pêcheries et de l'application des lois réglementant les engins de pêche, les membres des communautés locales ont constaté une augmentation des prises par unité d'effort, une augmentation de la taille des poissons capturés, une augmentation de l'abondance des juvéniles, la réapparition de certaines espèces, une restauration progressive des habitats, une augmentation de la capacité locale à gérer leurs ressources, une amélioration des relations entre les communautés locales et les autorités locales, une diminution de l'utilisation des sennes de plage et une augmentation des revenus économiques tirés de la pêche. Le suivi a révélé une multiplication par dix de la biomasse de poissons entre 2013 et 2015 dans les zones réglementées, tandis que la biomasse de poissons dans les zones interdites à la pêche des ZPM a doublé au cours de la même période. Le plan de gestion établit également légalement le premier sanctuaire de requins de Madagascar dans la baie d'Antongil, une zone d'habitat importante pour les requins avec au moins 19 espèces présentes qui sont connues pour être exploitées, dont un tiers est menacé d'extinction.

Bénéficiaires

100 000 personnes de 26 zones marines gérées localement (LMMA) dans la baie d'Antongil.

Objectifs de développement durable

Histoire

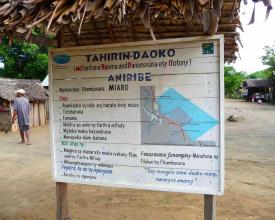

Les réserves marines gérées localement dans la baie d'Antongil sont organisées en un réseau de 26 réserves qui font à leur tour partie d'un réseau national de réserves marines gérées localement - le réseau MIHARI. En octobre 2015, les communautés autour de la baie d'Antongil ont eu l'honneur d'accueillir plus de 150 membres du réseau MIHARI venus de tout le pays pour le forum national annuel. Les associations de pêcheurs de la baie d'Antongil étaient incroyablement fières de montrer à la fois aux autres communautés locales de tout Madagascar le travail qu'elles avaient accompli et tout ce qu'elles avaient réalisé grâce au plan de gestion, aux dinas et à leur implication dans le CCS - qui sont les premiers du genre dans le pays. L'atmosphère de ce forum d'une semaine était festive ! Des représentants du gouvernement, des visiteurs du Pacifique où les réserves marines gérées localement sont un outil de gestion bien développé, des communautés locales, des jeunes et des représentants d'ONG se sont réunis sous des tentes, sur l'herbe, sur le sable, dans des huttes de village pour des discussions formelles et informelles sur la meilleure façon d'avancer vers un objectif commun d'amélioration de la gestion locale des réserves marines. Pour de nombreux membres des communautés locales, c'était la première fois qu'ils avaient l'occasion de discuter directement, sur un pied d'égalité, avec des fonctionnaires de haut niveau venus d'Antananarivo (la capitale de Madagascar), et leur plaisir de voir leur travail reconnu à ce niveau était immense. En conséquence directe de certaines des discussions tenues, le gouvernement a lancé la préparation d'un nouveau décret national sur les aires marines protégées gérées localement, qui est actuellement en cours de finalisation. À la fin de l'événement, un concours du plus grand poulpe élevé dans les zones saisonnières interdites à la pêche de la baie d'Antongil a été organisé et le gagnant pesait un énorme 6,2 kg.