KLIPPS - Evaluation method for the human-biometeorological quality of urban areas facing summer heat

KlippS

Landeshauptstadt Stuttgart, Amt für Umweltschutz, Stadtklimatologie

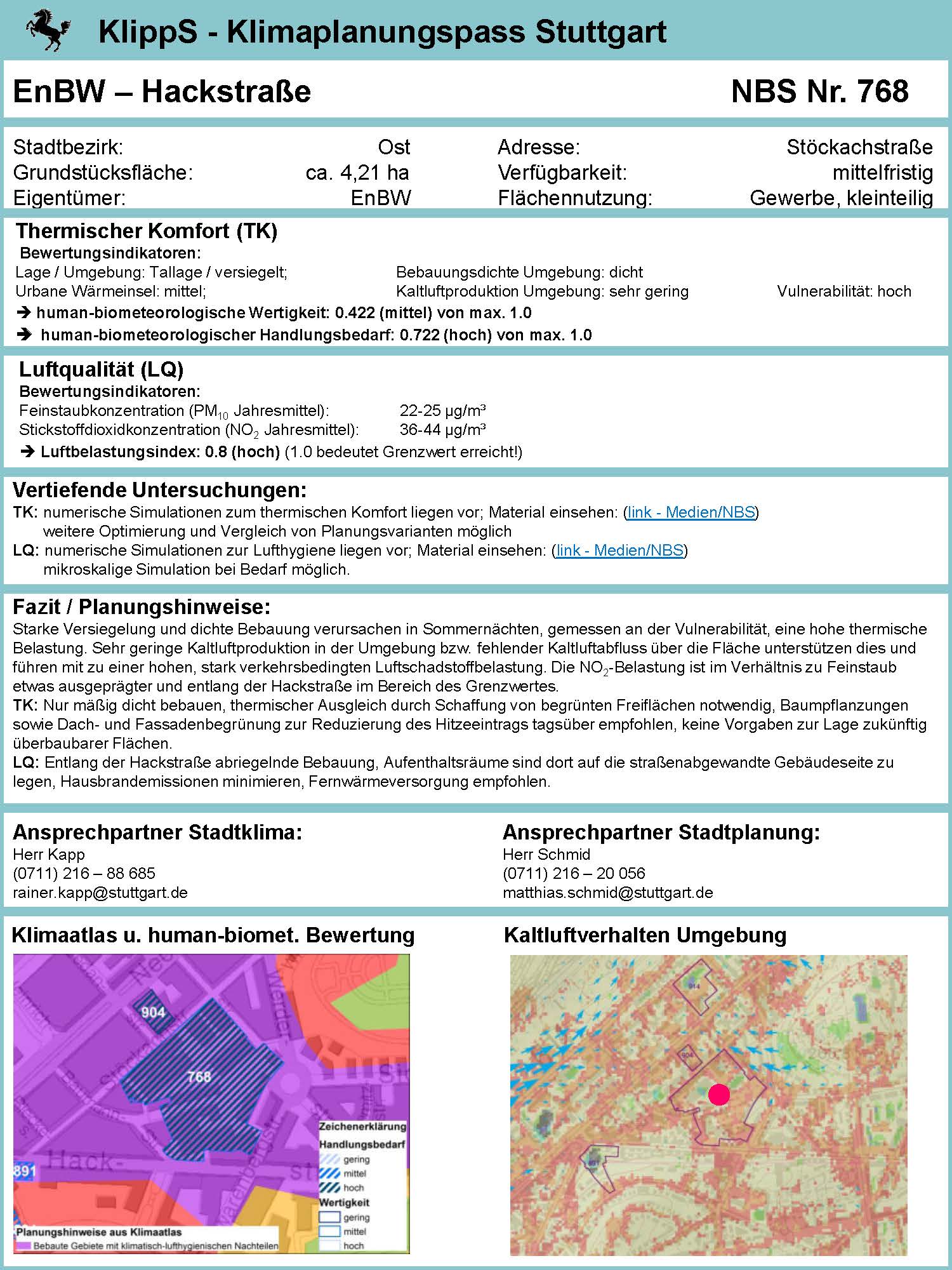

In addition to improving overall conditions related to increasing temperatures, the city of Stuttgart has designed an innovative project “KlippS – Climate Planning Passport Stuttgart” based on quantitative findings in urban human-biometeorology, for improving human thermal comfort. The KlippS project calculates the human thermal sensation under “warm” category during the daytime in summer. KlippS is divided into two phases: the first phase is concerned with a rapid evaluation of human heat stress for the areas involving “sustainable building land management Stuttgart”, the second focuses on numerical simulations at high-risk urban areas related to heat.

KlippS provides the following remarkable issues on a planning-related potential to mitigate local human heat stress:

a) innovative program involving the human-biometeorological concept which represents a new interdisciplinary field

b) various spatial scales including the both regional and local ranges on the basis of the systematical two-phase method

c) quantitative approach to human heat stress by using dominant meteorological variables such as air temperature T, mean radiant temperature MRT and thermophysiologically equivalent temperature PET

As an ongoing project, the outputs of the KlippS project have been discussed in the internal meetings with the Department of Administration as well as the local council in the city of Stuttgart. On the basis of the meetings, the practical measures are provided for the implementation as soon as possible.

People suffer heat stress through the combination of extreme hot weather on the regional scale and the inner urban complexity on the local scale. In principle, three options exist to mitigate the local impacts of severe heat on citizens:

a) heat warning systems of national weather service

b) adjustment of the individual behavior towards severe heat

c) application of heat-related planning measures

While both a) and b) work on the short term, option c) represents a long-term preventive way. In this perspective, KlippS was designed to develop, apply and validate measures, which contribute to a local reduction of severe heat.

The KlippS project was addressed at a lot of meetings and workshops, including at the public workshop “Climate change and Adaptation in Southwest Germany”, attended by 250 participants, on October 17, 2016 in Stuttgart. In addition to the workshops, KlippS was presented at many national and international scientific conferences.