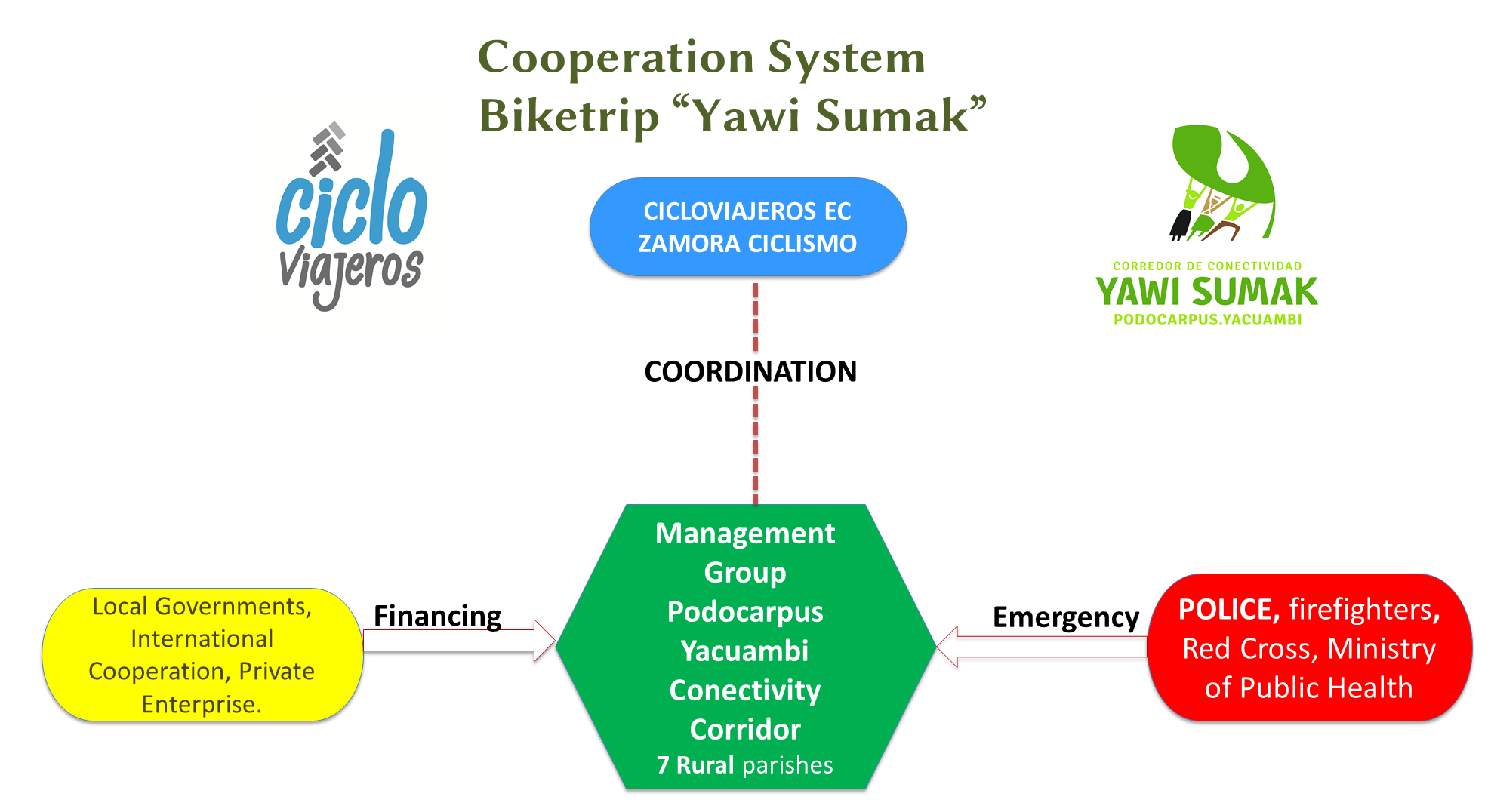

Carry out coordination meetings between bicycle groups and CPY connectivity corridor promoter group to define the budget, the route, the road map, the responsibilities and the message that will be transmitted in the current edition, for example: groups ethnic, spectacled bears - andean bears (Tremarctos Ornatus), mountain tapir (Tapirus pinchaque), water resource or etc.

In a second moment, all the actors meet: environmental authority, private company and aid institutions to agree on logistics, support issues and the contingency plan to ensure the safety of cyclists.

The structure and communication in a government space are key to the success of the event, sometimes it is complicated to handle certain conflicts for institutional leadership and protagonism.