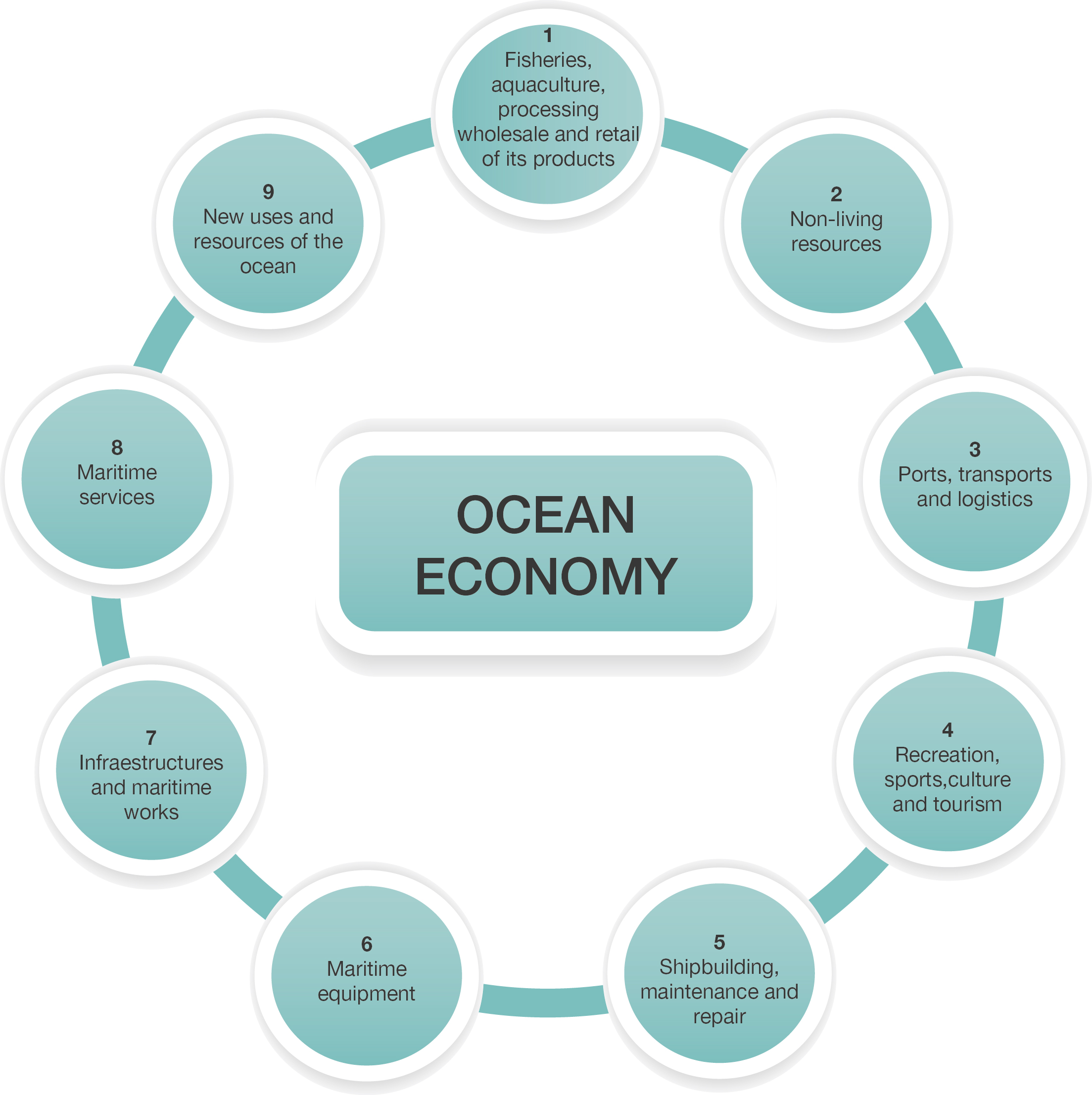

The scope of the Ocean Economy, considered in the Portuguese Ocean Satelite Account (OSA), aggregates activities in two main areas: "established activities" and "emerging activities” which, in turn, are divided into groups. It considers nine groups, eight of which correspond to established activities (groups 1 to 8). The last group (group 9) includes new uses and resources of the ocean, which congregates emerging activities (see figure). The adopted criterion for the classification of economic activities as established or emerging obeyed the international logic of maturity level of the markets, namely what is followed in the EU, in the study “Blue Growth” for the purpose of international comparisons.

Overall, we adopted a value chain logic considering, inter alia, the level of industry disaggregation permitted by the National Statistical System. Given this restriction, the methodological option was to consider Maritime and Marine Equipment Services as independent groups, including cross-economic activities in other groups.